Political Theories for Students

.pdf

C a p i t a l i s m

Critical Views

Structurally, there are some problems with capitalism. Because growth is driven by the desire for profit, it fluctuates according to the number of opportunities and openings. When an opportunity appears, capitalists hurry to take advantage of it and, consequently, there is an economic boom. Eventually, however, the market will be saturated and the boom will end, beginning a recession. Investment ends and the economy takes a dive.

Karl Marx published his criticisms of the ups and downs of the market in his 1867 work Das Kapital. Marx said that the growth was not only unsteady because of opportunities seized and missed, but also because of the natural progression toward industrialization and big business which, as explained earlier, makes the booms and recessions of the market more stark and profitable or, in the case of a recession, painful. Big business is not only encouraged by the advent of technologies which allow improved efficiency, but with recessions as well. When the market goes down, some firms will do better than others. The companies that have fared well usually swallow those that have not and become even larger and more successful than they were before.

John Maynard Keynes, an English economist, published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936. In his book, Keynes not only agrees with Marx that the ups and downs of a market economy are problematic, but goes further to say that it is possible for an economy to remain in a recession without periodic booms to balance it out. In terms of unemployment, Keynes felt that communal investment was the best way to fight this stagnation.

Another criticism of market–driven growth is the products produced by the capitalists can cause as much harm as good. Since the products are generally regulated only by customer demand, negative side effects often go hand in hand with production of goods. Toxic waste, unnecessary products, wasteful packaging, and poor working conditions are all side effects that accompany the products consumers demand.

There is heavy debate on how to deal with the apparent evils of capitalism. Some argue that the problems are not with capitalism but are actually lodged in the attempts to fix it. Well–meaning measures to curtail the market may lead to problems. The market should be left as independent as possible to ensure optimal operation. On the other hand, others advocates intervention and social welfare to distribute wealth more fairly, promote competition and deal with undesirable products of the market such as pollutants. Today, there are no advanced capitalistic countries that

allow complete market freedom without social welfare to compensate for pockets of poverty. In the United States, these transfer payments for health benefits and pensions comprise ten percent of the total consumer income. In Europe the percentage is much higher.

In making his case for capitalism in Capitalism: Opposing Viewpoints, Howard Baetjer Jr. writes:

This is the virtue of the free economy. The whole fabric of economic interactions is freely chosen, cooperative, and generally beneficial. Each party to an exchange believes he is benefiting. This point bears emphasis because so many believe that in capitalism the rich get richer at the expense of the poor or that the seller of a good exploits the buyer, or vice versa, so that one is better off and the other worse off. When one is free to exchange in a transaction or not, he does so only when he believes he will be better off for it. Think about your trips to the ice cream shop: you put your money down for the ice cream; they put down the ice cream for the money. You care for the ice cream more than the money at that point, and they don’t want the ice cream, they want the money. Everybody goes away content. There is a mutual ‘thank you’ as you exchange goods and money, because you both are better off...

People ought to be free economically as well as every other way. Laissez–faire is a great system, both practically, because it works to the increasing, as well as the well–being of all, and ethically, because it suits basic principles of decent interpersonal behavior. It is a system that deserves our hearty support.

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•There is a similarity between the changes that occur with capitalistic production and Marxist theory. The material basis of production goes through a series of shifts under both systems that alter the structure of civil institutions and the laws that govern them. Compare and contrast Marxist theory with Adam Smith’s theory of capitalism.

•How will the European Union affect the capitalism within its borders? Will the common currency promote a common capitalism, or will countries retain their beliefs and practices regardless of their neighbors’ differences? Will Germany’s economic strength remain, or will it lose its stature as it joins with the rest of the continent?

•James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers that governmental power might one day become less of a threat than that of the effects of freedom and personal liberty. Are his predictions are coming true? His checks and balances system protect us from the government, but we do not have a

4 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C a p i t a l i s m

similar system to protect us from the corporations that provide us with goods and services.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Beatty, Jack, ed. Colossus. New York: Broadway Books, 2001.

“Capitalism Theory: Frequently Asked Questions.” Available at http://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/shadab/capit–2.html.

CIA World Factbook. United States, 2000.

Commire, Anne, ed. Historic World Leaders vol. 5. Detroit, MI: Gale Group, 1994.

Ebenstein, William and Edwin Fogelman. Today’s Isms: Communism, Fascism, Capitalism, Socialism. New Jersey: Pren- tice–Hall, Inc., 1985.

Galbraith, John Kenneth and Stanislav Menshikov. Capitalism, Communism and Coexistence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1988.

Hampden–Turner, Charles and Alfons Trompenaars. The Seven Cultures of Capitalism. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1993.

Hooker, Richard. “Capitalism,” The European Enlightenment Glossary. Available at http://www.wsu.edu/dee/GLOSSARY/ CAPITAL.HTM.

Kronenwetter, Michael. Capitalism vs. Socialism; Economic Policies of the U.S. and U.S.S.R. United States: Michael Kronenwetter, 1986.

Leone, Bruno. Capitalism: Opposing Viewpoints, Minnesota:

Greenhaven Press, Inc., 1986.

Martella, John. “Philosophy, Economic History, and the Rise of Capitalism.” Drury University, 1992.

Tracinski, Robert. “The Moral Basis of Capitalism,” The Center for the Moral Defense of Capitalism, 1998. Available at http://www.moraldefense.com/Philosophy/Essays/The_Moral_ Basis_of_ Capitalism.htm.

Further Readings

Helpful internet sites include: http://www.capitalism.org; http:// www.CapitalismMagazine.com; http:// www.moraldefense.com; http://www.sharedcapitalism.org; and http://www.naturalcapitalism.org. These sites give current information on how Capitalism operates in the world today.

Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production. 1886. Provides a critique of capitalist theory and practice.

Pryor, Frederic, A Guidebook to the Comparative Study of Economic Systems. 1985. Provides general information on capitalism.

Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations. 1776. This is the original text of capitalism.

SEE ALSO

Conservatism, Liberalism, Marxism

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

4 1 |

OVERVIEW

Communism is a political and economic system in which citizens share property and wealth based on need. Private ownership does not occur. The idea of communism was set forth by Plato in The Republic in the 300s B.C. Plato’s ideas were followed by those of Sir Thomas More, who in the sixteenth century described utopias based on common ownership. Communism did not become a formal political system until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when Karl Marx brought communistic ideas to center stage. It was further developed and implemented by Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union, and after World War II, began to spread to countries such as East Germany, China, and Poland.

As the twentieth century drew to a close, communism began to experience problems. Though the most oppressive form of communism, known as Stalinism, had become obsolete, the state–owned systems were not able to provide for the public. One–party systems seemed to disturb personal freedom and create massive unrest. China began to allow private ownership in the 1970s and 1980s. Mikhail Gorbachev reformed the Soviet Union in the 1980s, and other communist regimes began to crumble in the 1990s. Many of these countries are still feeling the pains caused by decades of mandatory communism.

Communism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? The state

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Revolution

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Work for state’s

benefit

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The state

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The state

MAJOR FIGURES Joseph Stalin; Mao Tse–tung

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE China, 1949–present

4 3

C o m m u n i s m

CHRONOLOGY

1848: The Communist Manifesto is completed

1917: Bolsheviks gain control in Russia

1924: Joseph Stalin becomes leader of Soviet Russia

1945: Soviet communists take control of Eastern European countries

1949: Mao Tse–tung’s Chinese Communist Party

gains control of China

1956: Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev denounces Stalin at Twentieth Party Congress

1958: Mao Tse–tung introduces the Great Leap Forward in China

1959: Fidel Castro and the Communists are empowered in Cuba

1966: Mao Tse–tung strives to bring China into the modern age with the Cultural Revolution

1989: The Berlin Wall falls in Germany

1991: The Soviet Union collapses

HISTORY

Communism is not a new idea. Industrial and political power was used for thousands of years to control the masses. Social prophets were born from this inequality, and they began to imagine a better system. The ideas that they came up with were communal.

Utopian Ideas

Amos, Hosea, and Isaiah of the biblical Old Testament all examined the possibilities of a different existence, free from control and exploitation and full of life, equality, and vigor. Jeremiah, born in 650 B.C., imagined a new beginning. Everyone would be provided for equally, young and old would commune together, and justice would be the fabric to hold everything together. Similarly, Jesus Christ suggested a utopia as well, created from love. Jesus felt that a communal life would arise naturally from spiritual and social development. It would lack selfishness and cruelty and would thrive with the spirit of humility, service and communism.

Plato The Greek philosopher Plato (428–348 B.C.) had more detailed ideas about how to improve upon reality. Plato lived during a war between Athens and Sparta and was inspired to invent a world without war. After having seen corruption thread its way through society, he became suspicious of any idea that allowed an individual to have greater importance than society as a whole. It was this sentiment that gave birth to his book, The Republic.

Plato’s ideas were based upon a desire for justice and equality that he longed to see in his society. . All necessities would be provided, but wealth would be prohibited. He argued that wealth creates negativity and laziness and that poverty begets apathy and a general distaste for life. He predicted that his perfect society would eat corn, wine, barley, and wheat. They would sleep on yew beds, wear garlands, and sing while they drank their wine. Plato’s Republic would consist of three classes: the artisans would build and produce food and clothing; the warriors would protect the city from whatever threats it encountered; and the guardians would preside over the city. The guardians were the smallest and most important group and should therefore be very carefully chosen and vigorously trained.

In the early centuries A.D. there were several Roman writers who focused on the ways in which society could be improved. They wrote about the evils of corruption and class struggle. They argued that community and shared material would foster a better system. The poet Virgil (70–19 B.C.) described a utopia with no fences or boundaries. Everything was shared.

During the reign of Henry II, towns sprouted up all over England. The towns needed to be able to provide for themselves, so the surrounding land was of great value to the inhabitants. However, gradually the nobility began to claim this land for its own purposes. Land that had formerly been communal for pasture was falling into private hands. The peasants, accustomed to cooperative production and communal living, were horrified by the nobles’ appropriation of the land. In 1381, communal ideals were asserted in the Peasants’ Revolt as the common folk demanded the return of the land.

Sir Thomas More Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) was affected by the tales of exploration that he had heard in his childhood. He was intrigued by the description of the people on the islands in Northern Africa who had no property but shared all the riches and despised the idea of personal property and status. These travel tales inspired More’s Utopia.

More wanted a new social organization. Utopia contains a slightly different version of communism than

4 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o m m u n i s m

earlier works. It described a sailor who found the island of Utopia (the Greek word for nowhere.) The people of Utopia lived in harmony and communion without the crime and indignity so common in England.

Through his explanation of the sailor’s experiences on Utopia, More criticized the English legal system, inequality, and described the evils of private property. Utopia was an agrarian state, supporting itself with its agriculture. Many citizens conducted trade during part of the year but returned to the land to help during the harvest. Each person had his own specialty.

On Utopia, each day was divided into eight hours for sleeping and six hours for work. The remainder of each day was spent freely. Any surplus labor was used to repair highways. There was a monthly exchange of goods through communism. Families gave away everything they were not using and took whatever they were in need of. Though no one owned anything, everyone was rich in that they were entirely provided for. Money and the collection of gold or riches were forbidden. Formerly valued items were used in the most common way possible. Gold and silver, for example, were made into utensils and chains rather than coins.

Utopia’s government was made up of its people. Each group of thirty families elected a magistrate. Each ten magistrates elected an “archpilarch,” and they elected a prince. Criminals were sentenced to slavery and the slaves would do the work that no one else in the community wanted to do. Utopia was the most substantial communal idea written since Plato’s

Republic.

Utopia became an English word to describe a flawless society. There were more examples and ideas of utopian communities, and these ideas spread throughout Europe. In the seventeenth century, John Locke (1632–1704) argued with other philosophers about whether or not communism existed in nature. Locke felt that it did not.

Other utopian writers and social reformers continued to speckle the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with new ideas about equality. Each had his own ideas of how to organize a perfect existence, and each thought that he had finally figured it out. Peter Chamberlen (1560–1631), a social reformer, introduced the idea that the backbone of any society was the worker who owned nothing. He made up the army, did the work, and had as much of a claim on the earth as did the noblemen. The abolition of wealth, he said, would simultaneously end poverty. If the rich were honest and strong of heart, the poor would not exist.

Owen In 1817, Robert Owen (1771–1858) began to tackle the problem of unemployment with his theo-

ries. England had recently gone through a year of overproduction, and the need for relief grew until the House of Commons created a Committee on Poor Laws. Owen wrote a paper for this committee, explaining that the world had been taken over by wealth. Machinery had decreased the need for labor and the common man was not able to earn enough to buy what he needed to support his family. Owen felt that the best solution was communism and cooperative creation. He advocated self–contained communities, though not isolated from the rest of the world.

Anxious to attempt his own utopia, Owen bought Harmony, Indiana in 1824. He came to America and tried to create perfection in his colony, New Harmony. It failed. The failure was blamed on absolute equality of payment, regardless of the work put out. Despite the failure, Owen continued to write and publish works advocating communism. Utopianism swept through the United States and the idea of community gathered momentum in Europe.

The Beginnings of Marxism

Karl Marx (1818–1883) started as an advocate of communism and eventually developed his own theory with the help of Frederick Engels (1820–1895). Karl Marx founded the Communist League in 1847. When he published The Communist Manifesto in 1848 with Frederick Engels, a new brand of communism arose. The Manifesto explained that communism was the natural last step in the progression of society In order to get to this socialist state, a country must first evolve through slavery, feudalism, and capitalism. It was the dissatisfaction with capitalism and the realization of the working class of its lot in life that would spark the revolution needed to overthrow the former way of government and begin anew. Marx and Engels argued that industry and power would fall into fewer and fewer hands and that, at the breaking point, revolution would bring properties back to a base at which they would be shared. A central committee would govern over a society of equal members. Marx described this as socialism, using the word communism only to describe the perfection eventually achieved after the wrinkles of socialism were ironed out.

The French Revolution in 1848 created massive socialist excitement. Government had been so thoroughly corrupted that people revolted against the minority that had been controlling them for so long. A provisional government was set up in Paris, promising employment and a new standard of living for all. Democracy began to appeal to more people than communism, and over the next century Karl Marx’s ideas lost importance in much of Europe, giving way to the beginnings of democracy and reform.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

4 5 |

C o m m u n i s m

Vladimir Lenin.

The Soviet Union

At the same time, however, communism was gathering speed in Russia. Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), the leader of an underground communist movement and a devout Marxist, became the leader of Russia when his Bolshevik party overthrew the provisional government in 1917. By this time, communism had become somewhat different than the utopia described by Plato. It was a totalitarian system with a single political party controlling the government and the means of production and distribution. The new regime, the Comintern, held its first congress in 1919. The Comintern established 21 conditions by which it would define itself. The communists wanted to set themselves apart from all other political movements. They wanted to be seen as unaffiliated with other related ideologies such as the older Social Democratic parties.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, a power struggle ensued between Joseph Stalin (1879–1953), the general secretary for the Comintern, and Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), the commander of the Red Army. Stalin eventually won the struggle and Trotsky was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1929. Stalin followed some of Lenin’s ideals, including economic policy and his interest in strengthening the Soviet state. Stalin completed the transition from marxism to communism, altering industry and agriculture to become communal.

Stalin and Lenin agreed upon the need for industrial advances, but this is where their similarities ended.

Stalin felt that, rather than waiting for revolution to come to pass in capitalist countries, the Soviets could stand on their own. He believed in a one– country system and structured his regime accordingly. Communist policy changed dramatically when Russia and Germany entered a ten–year peace agreement in September 1939. Adolf Hitler, chancellor of Germany, was free to wage war against France and England. Until Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the Communist parties were told to condemn the allied powers of Western capitalism.

Stalin also required the other Communist parties to conduct purges similar to his own. The purges were designed to eliminate disloyalty and skepticism in the ranks and resulted in the deaths of many members of the Soviet party. Stalin asserted his power through personal agents and through the secret police rather than through party channels, as Lenin had. Police violence quashed objections and this oppressive version of communism became known as Stalinism. Because of this change in policy, the party structure weakened. Internationally, other Communist party leaders mimicked Stalin’s hierarchy and it became the defining nature of Communism.

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, much of the world expected a quick Soviet defeat. Stalin held his ground, however, and many of the evils of his rule were forgotten as he impressed the international community with his military prowess.

The Spread of Communism

While the Soviet Union and Germany were at war, Yugoslavia’s Communist movement, led by Marshal Tito (1892–1980), fought its way to power. Communism in Yugoslavia was modeled after the strict Stalinism. In other countries, Communist ideology was slowly replaced with anti–Nazi ideals. In 1943, the Comintern dissolved. It was no longer a tool for Stalin’s control, and its end gave weight to Stalin’s claim that the Soviet Union had abandoned its revolutionary ideas in favor of nationalism and security.

Stalin’s political and military superiority led him to create new policy. He decided to establish political regimes in the countries bordering the Soviet Union and that his country should be internationally recognized as the authority on Communism. His army, still in Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and East Germany when World War II ended in 1945, installed regimes similar to its own. Communism was also implemented in Czechoslovakia and North Korea. Yugoslavia and Albania also became Communist, but on

4 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o m m u n i s m

their own accord rather than under the fist of Soviet Russia.

There were three phases under which the countries adopted Communism. The first was a coalition of Communist and Socialist parties in the name of genuine improvement, which lasted for several years in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia. In East Germany and Poland, there was a much weaker coalition that gave deference to the Communist parties. Yugoslavia and Albania had even less Socialist party freedom. The Communists required fusion of all other Socialist parties and silenced opposition with varying degrees of legality. By 1949, all of the Communist countries existed in the third phase, without freedom of parties and subject to oppression and violence. The Socialist and peasant parties were attacked and extinguished.

Yugoslavia was different. The Communists, led by Tito, were heavily supported because of their role in the war. The People’s Democracy set up in the country was more closely related to Communist political structure than to other democratic countries.

In European countries outside of the Soviet bloc, the Communist parties had trouble clinging to the status they had held during the war. The parties in Italy and France retained relatively high percentages of support, but never held high office. Their power was limited to acts of disorder in line with Soviet policy.

After the war, several Communist parties had evolved in Asia because of the Western resistance to nationalism. In 1948, Communist movements erupted in Malaya, Indonesia, and Burma. After the surrender of Japan in September 1945, the communists under Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) collected power in Indochina. By the end of 1946, the Communists in the north were fighting the south. This was the beginning of the Vietnam War, which lasted until 1975. India’s Communist party gathered momentum after having supported Britain and experimented with Soviet–style violence after India’s independence but refuted this policy in 1950.

In China, Mao Tse–tung (1893–1976), also known as Mao Zedong, led the Chinese Communist Party to power in 1949. Though his party had developed with the help of the Soviets, Mao was not interested in being recessive. His party had won after a long guerrilla war. Stalin was unhappy with Mao’s autonomy and had planned to treat China as he treated the other countries in the Soviet bloc. Geographically and economically, however, China was in a stronger position to become its own entity and, furthermore, to become the Communist standard by which the rest of Asia measured itself. Other Southeast Asian countries

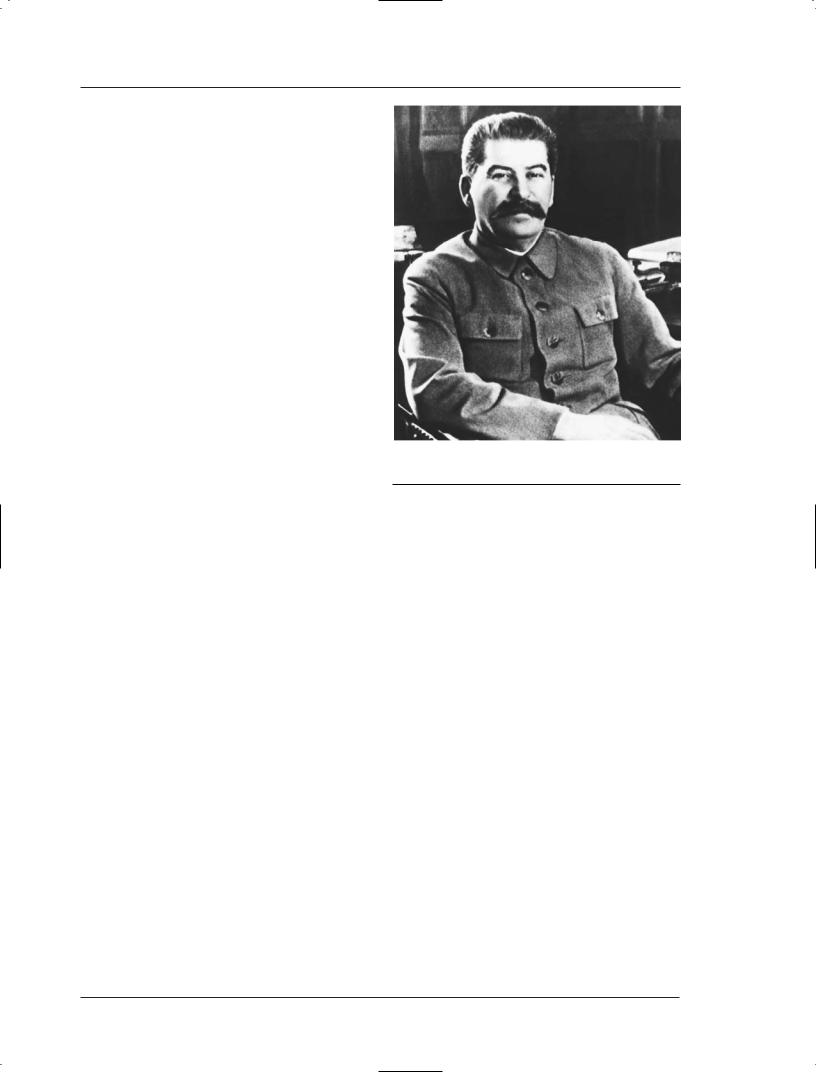

Joseph Stalin. (AP/World Wide Photos)

did follow China’s example. North Vietnam became communist in 1954. In the 1970s, South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia also became communist.

There was increasing dissension between the Soviet Union and China. In essence, both countries wanted to be the international Communist leader. On the surface, they fought over doctrine and details.

The Struggle for Power and Reform

Stalin continued to purge his population and those of the border countries. His expansion provoked a counter–offensive from the West, including the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949, which created a permanent defense for Western Europe, and the creation of the atomic bomb which, from 1945 to 1949, remained in sole possession of the United States. Stalin refused the offer of the Baruch Plan, calling for international control of atomic weapons. Instead, he finally succeeded in creating his own atomic bomb in 1949, and the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States had begun.

Trouble was brewing between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Tito was unwilling to succumb entirely to Soviet control, and Stalin was unwilling to allow the Communist country to remain autonomous. The Yugoslav Communist Party was expelled from the Cominform, the new group of Communist parties.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

4 7 |

C o m m u n i s m

Yugoslavia’s independence created a new ideal—it had survived its challenge to the Soviet Union. The Yugoslavian Communists could now speak more freely about Soviet Communism.

Reacting to Yugoslavia’s breach, Stalin tightened his grip on the remaining countries and renewed the force with which he purged his population of anything anti–Stalin. The countries in the Soviet bloc were overflowing with anti–Stalin sentiment by the time he died in 1953, largely because of his quest to eliminate such feelings.

In the east, Korea was having a struggle of its own. After the defeat of Japan, Korea had been split in two with a Communist government in the north and a non–Communist government in the south. Both claimed to be the government for the whole country, and when North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, the United Nations condemned the aggression and approved American assistance to South Korea. There were now Communist struggles under way in Vietnam, Korea, and Eastern Europe.

When Stalin died in 1953, another power struggle ensued in the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971), the first secretary of the Communist Party, ultimately won control. He wanted desperately to undo what Stalin had put in place and to create a Communism not synonymous with misery and mass murder.

Undoing Stalinism Khrushchev developed a policy of cooperation and integration with the satellite Communist countries. This replaced Stalin’s policy of exploitation. He established economic and political freedoms as well. He also tried to reconcile with Tito and Yugoslavia. The Soviet Union signed an agreement with Yugoslavia in 1956, stating that each Communist country was its own entity with none having the right to subject authority over others.

Also in 1956, Khrushchev delivered a speech critical of Stalin. Though this speech was not published in the Soviet Union, its text was published by the United States and was widely circulated among Communists worldwide. His comments sparked a feeling of freedom in the Soviet Union and began a wave of public criticism that had been suppressed for 25 years.

Internationally, Khrushchev’s statements began a wave of criticism toward Stalin–like leaders in other countries. Hungary’s leader was unseated and revolution began. The Soviet Union invaded Hungary in 1956 to end the revolution. After this seemingly contradictory act, Communists began to question Soviet leadership.

In 1957, Communist parties met in Moscow. At China’s insistence, the Soviet Union retained its leadership and, for a while, the rift between China and the Soviet Union seemed to evaporate. In 1959, however, the chasm widened. China grew suspicious of Soviet talks of “peaceful coexistence” with the United States, and the Soviet Union did not support China in its attacks on India. Economic relations were severed and the Sino–Soviet split continued.

In 1961, the Soviet Union began a public criticism of China. The struggle increased and destroyed the idea that Communism was a single viewpoint. The Soviet claim of leadership was weakening, and Communist parties divided themselves into pro–Soviet or pro–Chinese factions. The fact that there was a dispute at all allowed greater debate and freedom within the Communist movement. Soviet control steadily declined. When the Soviet Union tried to swallow Romania into its bloc, Romania resisted and remained outside.

When Khrushchev lost power in 1964, his successors tried to reunify the Communist movement. In 1969, 75 Communist parties met in Moscow. However, only 9 of the 14 parties in power were there. Asia and Africa were not well represented, and Cuba sent an observer rather than a representative. The conference was unsuccessful at rejuvenating the Communist union.

Reform was a reoccurring problem in Communist countries. The only country to attempt reform with mild success was Yugoslavia, who allowed its collective farms to fade away after their creation. Yugoslavia also created the Workers’ Councils to provide a voice to the factory workers. Furthermore, Yugoslavia argued that revolution was not necessary for Communism, that the Communist party did not need to be a one–party system, and that war grows from multiple powers in conflict, not simply from threats from the United States.

In Czechoslovakia, reform was chaotic. Alexander Dubcek (1921–1992) came to power in 1968 and tried to liberalize the country. He wanted to install civil liberties, a judiciary, and other democratic ideas. The Communists asserted their intentions to remain in the system, but Soviet leaders responded by invading Czechoslovakia in 1968 to protect against reform. This invasion surprised the international community and was seen as a Communist attack against other Communists.

Hope of détente, or peaceful coexistence with the West, gathered momentum in the 1970s. The international community began to envision acceptance between the Communist and non–Communist states.

4 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

C o m m u n i s m

However, the Soviet leadership stated that it had no intention of changing its position, and countered this with its 1979 invasion of Afghanistan.

Eventually, the Soviet Union began to face trouble. Its economic growth slowed down, and criticism of its policies thrived in the intellectual community. Mikhail Gorbachev became the general secretary of the Soviet Union in 1985 and the president in 1988. He supported structural reform. Gorbachev announced that the Communist revolution had no place in his country, and his relaxed policies allowed increased freedom in the satellite countries.

Though Communism was waning in Europe, the Soviet Union, and Africa, it was gaining speed in Cuba, North Korea, China, and Vietnam. The Tiananmen Square student demonstrations in China in 1989 were violently suppressed in an attempt to prevent anarchy. Though China had also reformed some of its policies, advocating foreign investment, relaxing collective agriculture, and expanding personal freedom, its Communism remained relatively unchanged.

Communism has not succeeded in many ways. It is synonymous with the Cold War, Castro’s oppression of his people, the Tiananmen Square uprising, and of the continual struggle of the countries in Eastern Europe. It is difficult to say what lies ahead, and whether or not Communism will yet prove itself to be a viable system or if it will continue to lose ground.

THEORY IN DEPTH

Communism is a very general idea. Of ancient origin, communism means a system in which society owns property collectively. Wealth is shared according to need. Specific ideas on communism have evolved over the years, ranging from the utopian versions of Plato and Sir Thomas More to the more dictatorial creation of Joseph Stalin.

Marxism

The first utopian communities were founded in the nineteenth century, but communism took a different road when examined by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels later in the century. Their Communist Manifesto was the first book identified as such, explaining the differences between the classes and the need for revolution to bring equality and, ultimately, Marxism.

Marxism has three main areas—philosophy, history, and economics. Philosophically, Marx agreed with George Hegel (1770–1831), a philosopher that he studied while he was creating his own theory. He

believed that history was a series of conflicts arising from two opposing forces, a thesis, and an antithesis. When the two forces collided, they formed a third entity, the synthesis. This synthesis then became its own thesis, inspired an antithesis, and spawned a new synthesis.

Marx also felt that philosophy had to become real. He did not feel that it was enough to be an observer, He argued that, though observation was useful, little would happen until someone actually did something. One must attempt to change the things that he or she was unhappy with, rather than continually philosophizing about them.

Marx felt that history was made up of different methods of provision. He identified five: the slave state; the feudal state; capitalism; socialism; and finally, Marxism. The slave state exploited the slaves too much to succeed indefinitely, the feudal state did not allow enough freedom, capitalism created too much inequality, socialism would begin to iron out the wrinkles, and Marxism would step in as the ultimate social achievement.

He also explained that the most important aspect of society was the way in which it provided for itself. Its economic means could include hunting and gathering or grocery stores and factories. The tools used and the groups who owned the modes of production were also important aspects to any given society.

Economically, Marx discussed class struggle. He focused on capitalism, arguing that it stole freedom from its citizens and created false feelings of security and equality. He felt that the blue collar workers focused on the ways in which they were not exploited rather than on the ways that they were.

Marxism included the idea of alienation as well. With capitalism, a worker produced goods. He was paid the same wage regardless of the profit his product generated for the capitalist. Marx felt that this separation from the direct profit of the good alienated the worker. He also felt that by selling one’s labor as a commodity, one was alienated from oneself. Workers were not paid for their value, but rather were given an amount which would allow them to provide for themselves.

When Lenin took power in Russia in 1917, communism had become a fusion of Marxism, Russian revolutionary tradition, and the personal ideas of Lenin. Lenin’s version of marxism came to be known as Marxism-Leninism, and was a sort of transition step between marxism and communism. The general idea of communism remained the same, that is that wealth is shared and that no one takes precedence over another.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

4 9 |

C o m m u n i s m

MAJOR WRITINGS:

The Communist Manifesto

The Manifesto, written by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, was published in 1848, right before the French Revolution. The Communist League, during its second Congress in 1847, commissioned Marx and Engels to write their new program. Marx and Engels responded with The Communist Manifesto.

The manifesto covers many areas. It begins by describing the bourgeoisie and their role in capitalism. It compares this class with the proletariat, the working class, who sells its labor in order to support itself.

The book explains the progression of capitalism, from world interdependence to centralization where the property becomes heavily concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. The world market is next, creating new opportunities, which, in turn, increase the scope and power of the capitalist. This is followed by the crisis that plagues capitalism—recession.

The manifesto describes the development of the proletariat. The working class slowly realizes that it is not happy with its lot, and will begin to appreciate how it can work collectively to change its situation. Through its struggle with the capitalists, the proletariat forms unions against its oppressors and learns to work in combination with one another. They become revolutionary and, eventually, succeed in ousting the government. They begin again, with their own brand of thought: communism.

Democratic Socialism

The Frankfurt Declaration of International Socialism in 1951 identified the goals and tasks of democratic socialism. The Declaration includes several ideas. It argued that socialism is international and does not demand rigid guidelines. Without freedom, socialism cannot exist, and socialism can only be reached through democratic channels.

The Declaration specifies that socialism would replace capitalism to ensure full employment, increased productivity and standard of living, equality of property, and social security. Public ownership might occur through nationalization or through private coop-

eratives. Trade unions were needed and economic decisions did not rest solely in the hands of the government.

Finally, the Declaration insisted that workers be compensated for their efforts. Socialism attempted to erase discrimination between social groups, races, and sexes. Imperialism was rejected, repression and oppression were shunned, and peace was reached through freedom. It was these ideas that defined the socialist movement in the twentieth century.

THEORY IN ACTION

The Soviet Union

Russia under Lenin Vladimir Lenin brought marxism to the Soviet Union. While Russia was in the middle of the World War I, civil unrest swept through the country. The monarchy was forced out, and Tsar Nicholas II was ousted during a peaceful revolution. The tsar was replaced with a Provisional Government designed to promote democracy and capitalism. Lenin was against capitalism and desperately wanted to bring communism into his country. Lenin’s Bolshevik party encouraged peasants to seize land. The Bolsheviks infiltrated trade unions, political parties, and local governments. They slipped in through the cracks. At the end of 1917, though they had only won twenty–five percent of the vote in the free elections the previous summer, they took control by force. The Bolsheviks removed the Provisional Government and claimed power for themselves.

Lenin turned the land over to the peasants and began negotiations to get the newly created Soviet Union out of the war, and his popularity jumped. However, his practices gradually began to differ from marxist theory. Soon after he took power, he began to silence opposition and eliminate threats. He justified political and social atrocities and seemed willing to ignore the ideals of a Marxist communist, equality and freedom, in order to reach his goals. He closed newspapers that were not pro–Bolshevik and he got rid of the Constituent Assembly, which had been elected in 1917.

Lenin collectivized agriculture and confiscated goods and products from the peasants. He redistributed the materials to his troops. He felt that this was a first step to socialism, but the peasants revolted and civil war sprouted up all over the country. The Bolsheviks changed their name to the Communist Party in 1919. Civil war continued until 1921. It was between the Bolsheviks and virtually everyone non–communist, the Whites. The Whites received

5 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |