- •Contents

- •Foreword

- •How to use this book

- •Advisory boards

- •Contributing writers

- •Contributing illustrators

- •What is an insect?

- •Evolution and systematics

- •Structure and function

- •Life history and reproduction

- •Ecology

- •Distribution and biogeography

- •Behavior

- •Social insects

- •Insects and humans

- •Conservation

- •Protura

- •Species accounts

- •Collembola

- •Species accounts

- •Diplura

- •Species accounts

- •Microcoryphia

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanura

- •Species accounts

- •Ephemeroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Odonata

- •Species accounts

- •Plecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Blattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Isoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantodea

- •Species accounts

- •Grylloblattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Dermaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Orthoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantophasmatodea

- •Phasmida

- •Species accounts

- •Embioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Zoraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Psocoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Phthiraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hemiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Megaloptera

- •Species accounts

- •Raphidioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Neuroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Coleoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Strepsiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Siphonaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Diptera

- •Species accounts

- •Trichoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Lepidoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hymenoptera

- •Species accounts

- •For further reading

- •Organizations

- •Contributors to the first edition

- •Glossary

- •Insects family list

- •A brief geologic history of animal life

- •Index

●

Lepidoptera

(Butterflies, skippers, and moths)

Class Insecta

Order Lepidoptera

Number of families 122

Photo: Swallowtail (Lamproptera meges) from

Thailand, drinking and expelling water. (Photo by

Rosser W. Garrison. Reproduced by permission.)

Evolution and systematics

For such a large group (arguably the second-largest group of insects, with approximately 150,000 described species), the fossil record for lepidopterans is meager. An estimated 600–700 fossil specimens are known, of which the earliest is a small moth, Archeolepis mane, from Dorset, England, dating from the early Jurassic period. Other fossils include leaf miners and preserved specimens in Cretaceous amber for primitive moths. More advanced families, including butterflies and noctuid moths, are known mostly from wings or preserved impressions of the insect; one of the most famous is a probable nymphalid butterfly, Prodryas persephone, from the rich shale Florisant fossil beds of the Oligocene period in Colorado. Fossils of immature stages are rare, but among them are a probable sphingid-like larva from the Pliocene in Germany and a possible noctuid egg from the late Cretaceous in eastern North America, for example. A factor contributing to the relative scarcity of fossil lepidopterans is their more fragile nature compared with other insect orders.

Lepidoptera is one of the two major orders (the other being the Diptera), along with scorpionflies, caddisflies, and fleas, forming the “panorpoid” complex. Trichoptera (caddisflies) is the sister group of Lepidoptera. Both possess either hairy or scaly wings, caterpillar-like larvae, reduction of mandibles in the adult stage, and similar wing venation. The Lepidoptera are distinguished by no fewer than 27 uniquely derived characters, including the possession of fleshy prolegs with hooklike crochets and a silk-producing spinneret in larvae, loss of the median ocellus, coiled sucking mouthparts, wings covered with a dense layer of overlapping shingle-like deciduous scales, and lack of cerci in adults.

The vast majority of lepidopterans are moths. Most moths have drab, somber colors; are nocturnal; do not have clubbed

antennae; and often rest with their wings held rooflike over the back. Skippers (Hesperiidae) are small, mothlike, dayflying butterflies that have a clubbed antenna ending in a curved tip called the apiculus, and they usually hold their wings over their backs. Butterflies, with about 19,000 described species, represent only about 13% of all Lepidoptera, though they probably are the most popular group. They differ from skippers in not having an apiculus at the end of the antenna.

Although the Lepidoptera make up an easily definable group, the higher classification below the ordinal level has undergone significant changes in light of newer phylogenetic classification methods. For many years, such terms as Rhopalocera (butterflies excluding skippers), Heterocera (all moths), and Microlepidoptera (micro-moths) were used to classify these insects. Later, all lepidopterans were classified according to the complexity of wing venation and wing-coupling systems. Most recent classifications use four suborders based on mouthpart morphological features and female reproductive systems. Within the Glossata, Monotrysian lepidopterans have genitalia with a single opening for both copulation and oviposition, while Ditrysian lepidopterans, which include about 98% of all the Lepidoptera, have genitalia with separate openings for copulation and oviposition. The most current classification recognizes about 30 superfamilies with 122 families; all except three occur within the Glossata.

Physical characteristics

Adult lepidopterans vary widely in size and structure. The smallest species are leaf-miner moths in the families Nepticulidae (forewing 0.06 in, or 1.5 mm) and Heliozelidae (forewing 0.07 in, or 1.7 mm); the largest known species is Thysania agrippina (Noctuidae) from the American tropics,

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

383 |

Order: Lepidoptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

D

B

A

C

Lepidoptera mouthparts (top left) and feeding techniques: Adults feeding on A. tree sap; B. nectar; and C. herbivore dung. D. Caterpillars (larvae) feed on leaves. (Illustrated by Patricia Ferrer)

with a wingspan of up to 11.2 in (280 mm). The smallest known butterfly species probably is Micropsyche ariana from Afghanistan or the Western pygmy blue of the United States. Both have a forewing length of 0.20–0.28 in (5–7 mm). The largest is Queen Alexandra’s birdwing of New Guinea, with females attaining a forewing length of up to 5.16 in (129 mm).

Adults possess a coiled tongue or proboscis (absent in primitive micro-lepidopterans, which retain mandibles) derived from the galeae of the maxillary palps; moniliform, pectinate, or clubbed antennae; large compound eyes; two lateral ocelli; a pair of erect scaled labial palps. They lack cerci. Wings usually are large compared with the small, elongate bodies and frequently are densely covered with overlapping scales that assume a wide variety of patterns and combination of colors. Wing venation varies. In small micro-moths, it can be reduced to a few veins. In many of the larger macro-moths and butterflies, however, venation consists of an oblong discal cell formed by reduction of the main basal veins (medius and part

of the radius) and a series of mostly unbranched veins radiating from the discal cell. Wing venation is similar in both wings, but the hind wing usually is smaller. The leading margin of the forewing often is crowded with veins providing strength to the leading edge.

Wing coupling is made possible by an extension of a jugal lobe (in primitive ghost moths) on the rear of the forewing, which overlaps and couples with the hind wing base during wing flexing. The most common type of wing coupling involves a small, strong cluster of hairs on the hind-wing base, called the frenulum, which is retained by a retinaculum at the base of the forewing. This mechanism allows for the hind wing to be extended in unison with the forewing in the course of flexing. A loss of the frenulum/retinaculum mechanism occurs in butterflies, skippers (except for one species), and certain genera of moths, resulting in an amplexiform wingcoupling device, where the strong anterior basal lobe of the hind wing overlies the base of the forewing.

384 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

Larvae generally are fleshy, soft, elongate animals with a chitinized semicircular head capsule. Antennae are small and inconspicuous. Mouthparts comprise a set of opposable mandibles. A small, erect, silk-producing organ, the spinneret, is present on the labium. The five-segmented legs on the thorax are small and end in a simple tooth, but they are lost in some families. The ventral part of the abdomen possesses differentiating number of fleshy prolegs on segments three through six and the tenth segment. The fleshy tips often bear various series of retractable hooks, called crochets, which allow larvae to grab on to a substrate. The surface of the body possesses setae, the placement of which is important in classifying various families. The body surface can be smooth or possess clusters of hairs, fleshy tubercles, or urticating hairs. Some small micro-moths are specialized leaf miners that have secondarily lost their legs and have a forward-projecting head with rasping mouthparts. Pupae generally are elongate with appendages fastened to the body. Many are encased in a silk cocoon, others are attached to a silk substrate by a small cluster of hooks called cremaster, and still others are accompanied by a single strong silk girdle. Some moth pupae are naked and occur in the ground.

Distribution

Lepidopterans occur on all land masses except Antarctica. The most northerly species may be the lymantriid moth, Gynaephora groenlandica, which has been taken on Ward Hunt Island (83°5 north latitude) in the Canadian Arctic. Lepidopterans are most diverse in the humid tropical zones.

Habitat

Eggs, larvae, and pupae occur in nearly all terrestrial habitats, where they often are found on or near their food plants. Larvae of a few species of moths are associated with aquatic plants in freshwater streams and ponds, and a few others (some species of Lycaenidae) live in ant nests. Adults visit nectar sources, and some species are attracted to carrion, oozing tree sap, or excrement. Adults often rest on foliage, tree trunks or any other substrate. Some species aggregate on shrubs, trees, or cave entrances.

Behavior

Butterflies and moths require a certain body temperature (usually between 77 and 79°F, or 25–26°C) to be able to fly, and they regulate internal temperature according to the environmental temperature. Butterflies of temperate areas increase heat absorption by spreading the wings, angling the exposed surface, and making direct contact with the substrate (dorsal basking) or by folding the wings above the body so that they are perpendicular to the sun’s rays (lateral basking). In the tropics, butterflies fly early in the morning and at dusk, seeking refuge in the shade when the temperature climbs too high. Most moths regulate their thoracic temperature through actively preheating the thorax by vibrating their wings and simultaneously contracting antagonistic flight muscles. To diminish heat dissipation, sphingids and other large moths have

Order: Lepidoptera

Automaris sp. using startling coloration to deter a predator. (Illustration by Patricia Ferrer)

insulating scales and hairs on the thorax and air sacs and diaphragms that separate the thorax from the abdomen so that the abdomen remains cooler.

Most adult butterflies and moths are solitary, but there are cases of gregarious behavior. Certain migratory species crowd together in wintering quarters, others form nocturnal roosts, and still others cluster on damp ground. Lepidopterans display a wide range of types of defensive behavior. Several larvae build protective cases, where they spend all or part of their time. For example, the bagworms of the family Psychidae form a case of silk covered with twigs, leaf fragments, and sand. Other larvae, feeding in exposed situations, show cryptic concealment, blending in by means of their green or brownish color with the leaves or bark where they feed or imitating part of a plant. When discovered, various species display startle or escape responses, such as exposing brightly colored and sharp, acrid osmeteria; regurgitating a brightly colored liquid; or faking sudden death by dropping to the ground.

Several aposematic larvae (larvae with warning coloration) in the families Lymantriidae, Limacodidae, Anthelidae, and others accompany their bright colors with urticating setae, or

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

385 |

Order: Lepidoptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

D

B

A C

Defensive techniques of some lepidopteran larvae. A. The twig-like larva of the owl butterfly (Caligo sp.); B. Aposematic coloration of the African monarch (Danaus chrysippus); C. Poisonous spikes of the saddleback caterpillar (Sibine stimulea); D. The snake-like larva of the victorine swallowtail (Papilio victorinus) and its earlier form, which looks like bird droppings (top). (Illustration by Patricia Ferrer)

spines, which are physically or chemically irritating or cause allergic reactions, making the larvae inedible to predators. Certain larvae even mimic snakes. The same defensive behaviors occur in adults; for example, several species pretend to be dead when they are handled, some arctiids discharge a foul-smelling yellow fluid from specialized thoracic glands, and pyralid and noctuid moths emit ultrasonic sounds to warn bats about their bad taste. Several diurnal lepidopterans exhibit aposematic coloration, announcing their distastefulness or mimicking truly inedible species. This is the case with several species that mimic wasps and bees with their orange-and- black or yellow-and-black abdomens and translucent wings and a few species complexes in which there is Batesian mimetism (e.g., monarch butterflies) and Müllerian mimetism (clusters of similarly marked distasteful species, for example monarchs and viceroys).

Most butterflies and moths disperse, but only about 200 species regularly migrate long distances, returning to the areas where they breed. Migratory butterflies are found among the pierids, nymphalids, lycaenids, and hesperids and moths in the sphingids and noctuids (night flight) and uranids (day flight). In northern parts of North America and Europe, many species display seasonal southward movements: certain butterflies fly south in late summer or autumn and then north from Central or South America or South Africa in spring. A particular individual of a migrating species is not able to undertake a complete round trip; the return trip is accomplished

by the offspring. The best-known example of a migrating butterfly is the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus, distributed from southern Canada to Paraguay in the New World. In North America three to five generations feed on milkweeds in the summer. In the fall they migrate south to overwintering places in California, Mexico, and Florida, where adults congregate in great numbers on certain kinds of trees. In the spring they begin their journey back north, laying eggs along the way before dying. The subsequent generation completes the return flight the following fall.

Feeding ecology and diet

Lepidopterans are predominantly phytophagous (plantfeeders), and 99% of them exploit higher plants (angiosperms); larvae feed on plant tissues, while adults feed mostly on nectar. The vast majority of these insects specialize in one (monophagy) or a few (oligophagy) food plants; only a small percentage feed on a wide range of food plants (polyphagy). Mouthparts of most adult butterflies and moths are designed for sucking, and almost all of them feed on nectar. Some lepidopterans complement their nectar-based diet with pollen, and others are saprophagous, sucking fluids on rotting fruits, carrion, dung, or droppings. Among the noctuids, for example, there are a few that feed on fruits that have been opened by other animals and others that have a strong proboscis and are able to pierce fruit skin. In the tropics a few species are able to suck the lachrymal fluids of cattle and other

386 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

mammals, including humans, while others prefer urine, excreta, and cutaneous secretions. Calpe eustrigiata, an oriental noctuid moth, has developed hematophagous habits, piercing the skin of mammals to feed on their blood. Lepidopterans also imbibe water and salts from the substrate.

Herbivorous larvae usually specialize in a certain tissue of the plant: leaves, flowers, seeds, buds, or wood. There are several endophytic species, the larvae of which spend their life digging galleries inside plant tissues. Most lepidopteran larvae are exophytic, however, feeding on the outside of plants. Some larvae have unusual diets. Micropterigid larvae feed on mosses, whereas adults, which have chewing mouthparts, feed on pollen. Certain larvae feed on lichens (some arctiids, noctuids, and lycaenids), fungi (some tineids), algae and diatoms on the surface of submerged rocks (aquatic pyralids), or ferns. There are some carnivorous caterpillars that feed on other insects. For example, certain Hawaiian geometrids prey on Diptera, and Asian noctuids eat scale insects. A few lycaenids feed on aphids, others on homopterans, and still others on ant eggs, larvae, and pupae. Some noctuid larvae live in the pitcher of the carnivorous plant Nephentes, where they eat the plant’s prey, and certain tineids and gelechiids steal prey from spider webs. Several microlepidopterans eat plant and animal derivatives, such as cloth, wool, fur, feathers, grains, dried fungi, paper, rotting wood, and droppings of birds and mammals.

Order: Lepidoptera

Swallowtail tiger (Pterourus glaucus) caterpillar defense display. (Photo by Kerry Givena. Bruce Coleman, Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

Reproductive biology

Most species reproduce bisexually, but some European species of psychids are parthenogenetic. Two mate-location strategies are known among butterflies: territoriality and patrolling. Territorial males perch on a post, from which they defend an area and attack and pursue intruders. Patrolling males fly through proper habitats in search of receptive females. Butterflies rely on visual stimuli to locate their mates and use pheromones produced by the male only secondarily, whereas moths generally locate their mates by pheromones liberated by the female to attract the male. Among butterflies, when the male spots a female of a specific shape or color, he pursues her. The female then drops to the ground, and the male may perform a courtship ritual, moving his antennae and wings around her. He also may liberate an aphrodisiac pheromone from the glands on his wings, legs, thorax, or abdomen (modified scales or brushlike tufts of hairs called androconia), which acts over a short distance and a short period of time. If the female is receptive, mating takes place. In moths the female produces pheromones from the abdominal glands (usually located between segments eight and nine) that act over long distances to attract males. Courtship typically is simple, and mating takes place shortly after the male reaches the female. Male receptors for the pheromone are in his bipectinate antennae and allow him to detect a single molecule of the pheromone.

Females insert the eggs into plant tissues with an ovipositor or wedge-shaped papillae anales, glue them to a substrate, or simply drop them during flight. In some Monopis species (tineids) the eggs are retained in the enlarged vagina until they are ready to hatch, and the larvae emerge immediately after

eggs are laid. Eggs can be laid singly or in batches; the number of eggs and their size depend on the size of the adult and the degree of alimentary specialization of the larva. Species with specialized monophagus diets produce a larger number of eggs of smaller size, which typically are dropped in flight; species with generalist polyphagus diets, on the other hand, tend to choose oviposition sites carefully. Eggs may pass through a diapause period in some species, during which they remain in a latent state; in temperate regions diapause may allow eggs to survive the winter or, in tropical regions, drought periods.

The duration of the larval stage varies with the species, its feeding ecology, the temperature, and the availability of food; it can range from 15 to 30 days to two years. When mature, the larva searches for a suitable place to pupate: in soil or litter, beneath a stone or bark (i.e., sphingids, notodontids, noctuids, and saturnids), or by rolling up a leaf and sewing the margins together with silk (i.e., tortricids and pyralids). Some larvae spin silk to attach themselves head downward to a support or to construct a protective web (arctiids), silken tube shelters (some pyralids and tineids), or cocoons (silkworm and gypsy moths). Pupae or chrysalids suspend themselves through a thread of silk from the cremaster. Emergence from cocoons takes place through caplike flaps with a secretion of fluid that dissolves the cocoon wall, or the insects may cut or force their way through the wall with sharp structures on the head.

In temperate areas most species spend short and lowtemperature winter months as eggs, as larvae in diapause, or as pupae and summer months as adults. In the tropics, where sea-

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

387 |

Order: Lepidoptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

A silk moth (Automeris cecrops) caterpillar in Arizona, USA. (Photo by Bob Jensen. Bruce Coleman, Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

sonal temperature differences are small, some species are present as adults all year. Seasonal variations for species occur in deciduous forests and savannas but are related to rainy and dry seasons. The average life span of an adult is only a few days or weeks, although some danaines and heliconines may live for as long as six months. The timing of flight is correlated with the life cycle of the food plant and whether the species overwinter. Species that overwinter as adults, such as the mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) and several Polygonia anglewings in North America, fly in early February and March. Species that overwinter as pupae fly next, followed by species that spend the winter as larvae and, finally, those that do so as eggs.

Conservation status

More than any other order of insects, lepidopterans have attracted the attention of conservationists. In all, 284 lepidopterans of 747 total insects are listed on the Red List of the World Conservation Union (IUCN); 25 are on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered species; and several others, including the giant birdwing butterflies of the Indo-Australian region, are listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Butterflies, in particular, have been accorded conservation status because they are easily seen, colorful, day-flying insects and

favorites with collectors. Collecting and commercial trafficking of butterflies often have been considered to pose a principal threat to their existence, but, as with many other insects, it is habitat loss that represents the primary threat. Although some subspecies of butterflies (e.g., Speyeria adiaste atossa from southern California and Cercyonis sthenele sthenele and Glaucopsyche lygdamus xerces from the San Francisco Bay Area) have become extinct in recent times, very little is known about the status of moths, because so few people study them. Many endemic species of micro-moths (e.g., Hyposmocoma species) from the Hawaiian Islands, for example, are known only from the original specimens collected about a century ago, and it has been postulated that many may be extinct owing to habitat loss and introduction of lepidopteran parasitoids.

Positive steps have been taken to preserve some species considered aesthetically beautiful or rare. One of the best success stories is that of the magnificently colorful birdwing butterflies (Ornithoptera and Troides) of Papua New Guinea. They represent a prime example of sustainable wildlife management by encouraging butterfly farming, breeding highly desirable species. Survival of the largest and most restricted butterfly in the world, Ornithoptera alexandrae, may depend on such a program. Natives have ranched this species and others. The practice advocates maintenance of habitat by encouraging

388 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

A monarch chrysalis in its late stage. (Photo by Ed Derringer. Bruce Coleman, Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

growth of the butterfly’s food plant. Some of the birdwings are offered for sale, and others are released into the environment. Butterfly-breeding farms also have cropped up in many global regions, and they annually ship thousands of living pupae to butterfly zoos throughout the world.

Significance to humans

Butterflies have always been a favorite insect motif in art; they are represented in Egyptian temples, Chinese amulets, Aztec ceramics, and an endless number of paintings, sculptures, gem carvings, textiles, glass, drawings, and poetry, symbolizing joy or sorrow and eternal life or the transience of life. In some cultures, butterflies and moths have a symbolic connection to the soul: the word for butterflies and moths in Russian means “little soul,” and in Greek it means simply

Order: Lepidoptera

A Delaware skipper (Atrytone logan) resting. (Photo by Larry West. Bruce Coleman, Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

“soul.” Some European traditions maintain that witches and fairies turn themselves into moths or butterflies to go inside houses. In the pre-Columbian cultures of Central America they were respected in religious and mythical traditions, representing souls of the dead, new plant growth, the heat of fire, sunlight, and various transformations of nature.

Many butterflies and moths fly from one flower to another and are major factors in pollination, and hence reproduction, of angiosperms. Some species are directly beneficial in that they have predatory larvae that feed on aphids and scales (e.g., several pyralids, lycaenids, noctuids, and blastobasids) or are parasites of plant-sucking leafhoppers (epipyropids). To this day, the silkworm is used in the production of textiles; the eggs of a gelechiid moth are employed commercially to raise the parasitoid wasp Trichogramma, which is released to control noctuid moths; and the larvae of a pyralid from South America are used in South Africa and Australia to keep in check invasive Opuntia cacti. In tropical areas of South America, New Guinea, Australia, Madagascar, and Africa, caterpillars are a complement of the human diet.

Because of their phytophagous nature, many caterpillars are major pests. Examples include leaf-rollers (Tortricidae), leaftires and webworms (Pyralidae), leaf miners (Incurvariidae and Gracillariidae), cutworms and armyworms (Noctuidae), underground grass grubs (Hepialidae), borers (Hepialidae, Cossidae, and Sesiidae), forest defoliators (Limacodidae and Geometriidae), stored fibers and foods pests (Tineidae, Gelechiidae, and Pyralidae), and crop pests (Tortricidae, Plutellidae, Gelechiidae, Noctuidae, and Pieridae).

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

389 |

1

2

3

5

4

6

8

9

7

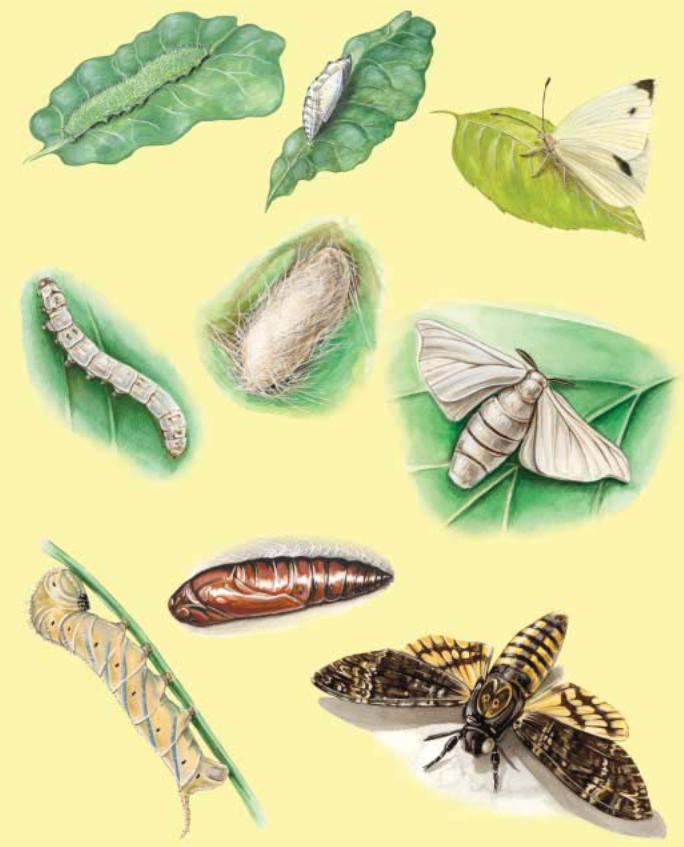

1. European cabbage white (Pieris rapae) larva; 2. Pieris rapae pupa; 3. Pieris rapae adult; 4. Silkworm (Bombys mori) larva; 5. Bombys mori pupa; 6. Bombyx mori adult; 7. Death’s head hawk moth (Acherontia atropos) larva; 8. Acherontia atropos pupa. (Illustration by Patricia Ferrer)

390 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

1 |

2 |

3

4

5

7

6

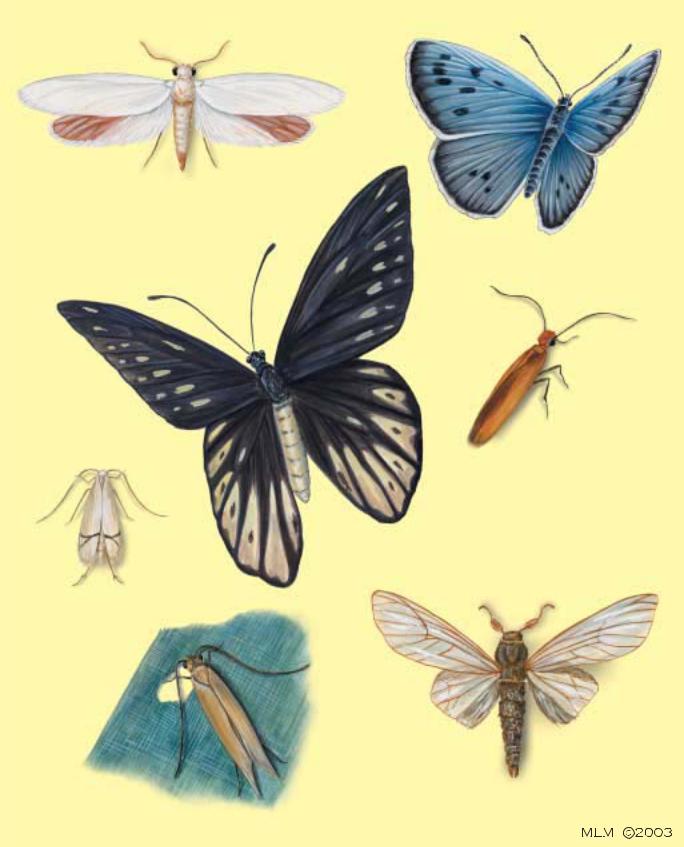

1. Yucca moth (Tegeticula yuccasella); 2. Large blue (Maculinea arion); 3. Female Queen Alexandra’s birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae); 4. Micropterix calthella; 5. Citrus leaf miner (Phyllocnistis citrella); 6. Webbing clothes moth (Tineola bisselliella) 7. Bagworm (Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis). (Illustration by Michelle Meneghini)

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

391 |

2

1

3

6

4 |

5 |

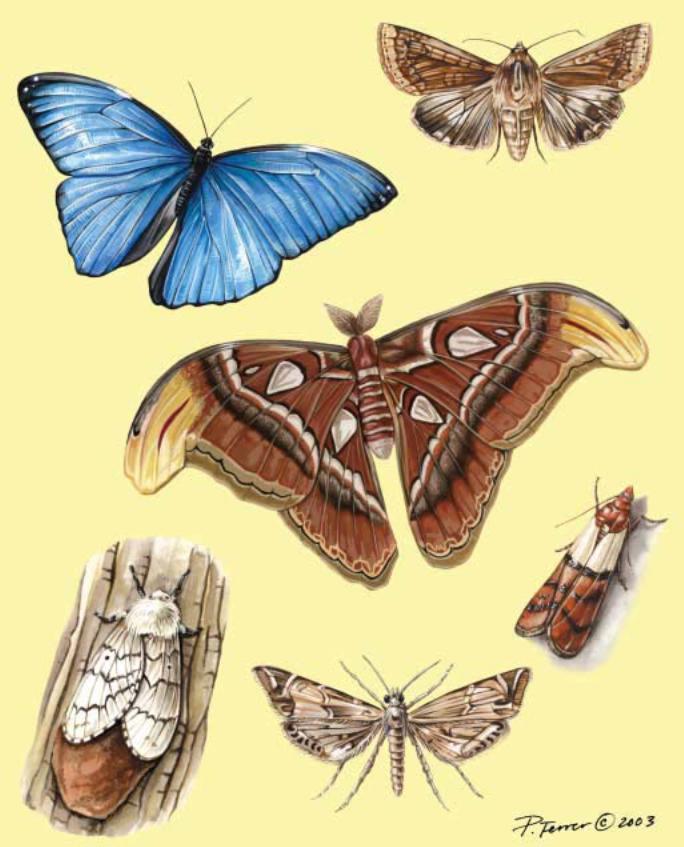

1. Blue morpho (Morpho menelaus); 2. Corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea); 3. Atlas moth (Attacus atlas); 4. Gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar); 5. Parargyractis confusalis; 6. Indian mealmoth (Plodia interpunctella). (Illustration by Patricia Ferrer)

392 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |