- •CONTENTS

- •INTRODUCTION

- •1 Getting Started

- •Better, Cheaper, Easier

- •Who This Book Is For

- •What Kind of Digital Film Should You Make?

- •2 Writing and Scheduling

- •Screenwriting

- •Finding a Story

- •Structure

- •Writing Visually

- •Formatting Your Script

- •Writing for Television

- •Writing for “Unscripted”

- •Writing for Corporate Projects

- •Scheduling

- •Breaking Down a Script

- •Choosing a Shooting Order

- •How Much Can You Shoot in a Day?

- •Production Boards

- •Scheduling for Unscripted Projects

- •3 Digital Video Primer

- •What Is HD?

- •Components of Digital Video

- •Tracks

- •Frames

- •Scan Lines

- •Pixels

- •Audio Tracks

- •Audio Sampling

- •Working with Analog or SD Video

- •Digital Image Quality

- •Color Sampling

- •Bit Depth

- •Compression Ratios

- •Data Rate

- •Understanding Digital Media Files

- •Digital Video Container Files

- •Codecs

- •Audio Container Files and Codecs

- •Transcoding

- •Acquisition Formats

- •Unscientific Answers to Highly Technical Questions

- •4 Choosing a Camera

- •Evaluating a Camera

- •Image Quality

- •Sensors

- •Compression

- •Sharpening

- •White Balance

- •Image Tweaking

- •Lenses

- •Lens Quality

- •Lens Features

- •Interchangeable Lenses

- •Never Mind the Reasons, How Does It Look?

- •Camera Features

- •Camera Body Types

- •Manual Controls

- •Focus

- •Shutter Speed

- •Aperture Control

- •Image Stabilization

- •Viewfinder

- •Interface

- •Audio

- •Media Type

- •Wireless

- •Batteries and AC Adaptors

- •DSLRs

- •Use Your Director of Photography

- •Accessorizing

- •Tripods

- •Field Monitors

- •Remote Controls

- •Microphones

- •Filters

- •All That Other Stuff

- •What You Should Choose

- •5 Planning Your Shoot

- •Storyboarding

- •Shots and Coverage

- •Camera Angles

- •Computer-Generated Storyboards

- •Less Is More

- •Camera Diagrams and Shot Lists

- •Location Scouting

- •Production Design

- •Art Directing Basics

- •Building a Set

- •Set Dressing and Props

- •DIY Art Direction

- •Visual Planning for Documentaries

- •Effects Planning

- •Creating Rough Effects Shots

- •6 Lighting

- •Film-Style Lighting

- •The Art of Lighting

- •Three-Point Lighting

- •Types of Light

- •Color Temperature

- •Types of Lights

- •Wattage

- •Controlling the Quality of Light

- •Lighting Gels

- •Diffusion

- •Lighting Your Actors

- •Interior Lighting

- •Power Supply

- •Mixing Daylight and Interior Light

- •Using Household Lights

- •Exterior Lighting

- •Enhancing Existing Daylight

- •Video Lighting

- •Low-Light Shooting

- •Special Lighting Situations

- •Lighting for Video-to-Film Transfers

- •Lighting for Blue and Green Screen

- •7 Using the Camera

- •Setting Focus

- •Using the Zoom Lens

- •Controlling the Zoom

- •Exposure

- •Aperture

- •Shutter Speed

- •Gain

- •Which One to Adjust?

- •Exposure and Depth of Field

- •White Balancing

- •Composition

- •Headroom

- •Lead Your Subject

- •Following Versus Anticipating

- •Don’t Be Afraid to Get Too Close

- •Listen

- •Eyelines

- •Clearing Frame

- •Beware of the Stage Line

- •TV Framing

- •Breaking the Rules

- •Camera Movement

- •Panning and Tilting

- •Zooms and Dolly Shots

- •Tracking Shots

- •Handholding

- •Deciding When to Move

- •Shooting Checklist

- •8 Production Sound

- •What You Want to Record

- •Microphones

- •What a Mic Hears

- •How a Mic Hears

- •Types of Mics

- •Mixing

- •Connecting It All Up

- •Wireless Mics

- •Setting Up

- •Placing Your Mics

- •Getting the Right Sound for the Picture

- •Testing Sound

- •Reference Tone

- •Managing Your Set

- •Recording Your Sound

- •Room Tone

- •Run-and-Gun Audio

- •Gear Checklist

- •9 Shooting and Directing

- •The Shooting Script

- •Updating the Shooting Script

- •Directing

- •Rehearsals

- •Managing the Set

- •Putting Plans into Action

- •Double-Check Your Camera Settings

- •The Protocol of Shooting

- •Respect for Acting

- •Organization on the Set

- •Script Supervising for Scripted Projects

- •Documentary Field Notes

- •What’s Different with a DSLR?

- •DSLR Camera Settings for HD Video

- •Working with Interchangeable Lenses

- •What Lenses Do I Need?

- •How to Get a Shallow Depth of Field

- •Measuring and Pulling Focus

- •Measuring Focus

- •Pulling Focus

- •Advanced Camera Rigging and Supports

- •Viewing Video on the Set

- •Double-System Audio Recording

- •How to Record Double-System Audio

- •Multi-Cam Shooting

- •Multi-Cam Basics

- •Challenges of Multi-Cam Shoots

- •Going Tapeless

- •On-set Media Workstations

- •Media Cards and Workflow

- •Organizing Media on the Set

- •Audio Media Workflow

- •Shooting Blue-Screen Effects

- •11 Editing Gear

- •Setting Up a Workstation

- •Storage

- •Monitors

- •Videotape Interface

- •Custom Keyboards and Controllers

- •Backing Up

- •Networked Systems

- •Storage Area Networks (SANs) and Network-Attached Storage (NAS)

- •Cloud Storage

- •Render Farms

- •Audio Equipment

- •Digital Video Cables and Connectors

- •FireWire

- •HDMI

- •Fibre Channel

- •Thunderbolt

- •Audio Interfaces

- •Know What You Need

- •12 Editing Software

- •The Interface

- •Editing Tools

- •Drag-and-Drop Editing

- •Three-Point Editing

- •JKL Editing

- •Insert and Overwrite Editing

- •Trimming

- •Ripple and Roll, Slip and Slide

- •Multi-Camera Editing

- •Advanced Features

- •Organizational Tools

- •Importing Media

- •Effects and Titles

- •Types of Effects

- •Titles

- •Audio Tools

- •Equalization

- •Audio Effects and Filters

- •Audio Plug-In Formats

- •Mixing

- •OMF Export

- •Finishing Tools

- •Our Software Recommendations

- •Know What You Need

- •13 Preparing to Edit

- •Organizing Your Media

- •Create a Naming System

- •Setting Up Your Project

- •Importing and Transcoding

- •Capturing Tape-based Media

- •Logging

- •Capturing

- •Importing Audio

- •Importing Still Images

- •Moving Media

- •Sorting Media After Ingest

- •How to Sort by Content

- •Synchronizing Double-System Sound and Picture

- •Preparing Multi-Camera Media

- •Troubleshooting

- •14 Editing

- •Editing Basics

- •Applied Three-Act Structure

- •Building a Rough Cut

- •Watch Everything

- •Radio Cuts

- •Master Shot—Style Coverage

- •Editing Techniques

- •Cutaways and Reaction Shots

- •Matching Action

- •Matching Screen Position

- •Overlapping Edits

- •Matching Emotion and Tone

- •Pauses and Pull-Ups

- •Hard Sound Effects and Music

- •Transitions Between Scenes

- •Hard Cuts

- •Dissolves, Fades, and Wipes

- •Establishing Shots

- •Clearing Frame and Natural “Wipes”

- •Solving Technical Problems

- •Missing Elements

- •Temporary Elements

- •Multi-Cam Editing

- •Fine Cutting

- •Editing for Style

- •Duration

- •The Big Picture

- •15 Sound Editing

- •Sounding Off

- •Setting Up

- •Temp Mixes

- •Audio Levels Metering

- •Clipping and Distortion

- •Using Your Editing App for Sound

- •Dedicated Sound Editing Apps

- •Moving Your Audio

- •Editing Sound

- •Unintelligible Dialogue

- •Changes in Tone

- •Is There Extraneous Noise in the Shot?

- •Are There Bad Video Edits That Can Be Reinforced with Audio?

- •Is There Bad Audio?

- •Are There Vocal Problems You Need to Correct?

- •Dialogue Editing

- •Non-Dialogue Voice Recordings

- •EQ Is Your Friend

- •Sound Effects

- •Sound Effect Sources

- •Music

- •Editing Music

- •License to Play

- •Finding a Composer

- •Do It Yourself

- •16 Color Correction

- •Color Correction

- •Advanced Color Controls

- •Seeing Color

- •A Less Scientific Approach

- •Too Much of a Good Thing

- •Brightening Dark Video

- •Compensating for Overexposure

- •Correcting Bad White Balance

- •Using Tracks and Layers to Adjust Color

- •Black-and-White Effects

- •Correcting Color for Film

- •Making Your Video Look Like Film

- •One More Thing

- •17 Titles and Effects

- •Titles

- •Choosing Your Typeface and Size

- •Ordering Your Titles

- •Coloring Your Titles

- •Placing Your Titles

- •Safe Titles

- •Motion Effects

- •Keyframes and Interpolating

- •Integrating Still Images and Video

- •Special Effects Workflow

- •Compositing 101

- •Keys

- •Keying Tips

- •Mattes

- •Mixing SD and HD Footage

- •Using Effects to Fix Problems

- •Eliminating Camera Shake

- •Getting Rid of Things

- •Moving On

- •18 Finishing

- •What Do You Need?

- •Start Early

- •What Is Mastering?

- •What to Do Now

- •Preparing for Film Festivals

- •DIY File-Based Masters

- •Preparing Your Sequence

- •Color Grading

- •Create a Mix

- •Make a Textless Master

- •Export Your Masters

- •Watch Your Export

- •Web Video and Video-on-Demand

- •Streaming or Download?

- •Compressing for the Web

- •Choosing a Data Rate

- •Choosing a Keyframe Interval

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Discs

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Compression

- •DVD and Blu-Ray Disc Authoring

- •High-End Finishing

- •Reel Changes

- •Preparing for a Professional Audio Mix

- •Preparing for Professional Color Grading

- •Putting Audio and Video Back Together

- •Digital Videotape Masters

- •35mm Film Prints

- •The Film Printing Process

- •Printing from a Negative

- •Direct-to-Print

- •Optical Soundtracks

- •Digital Cinema Masters

- •Archiving Your Project

- •GLOSSARY

- •INDEX

7

Using the Camera

Photo credit: Jason Hampton

The sweeping panoramas of Lawrence of Arabia, the evocative shadows and compositions of The Third Man, the famous dolly/crane shot that opens A Touch of Evil— when we remember great films, striking images usually come to mind. Digital video

cameras are the hot topic among filmmakers these days, and shooting your film is the single most important step in a live-action production. Shooting good video requires more than just recording pretty images. As a director, the ability to unite the actors’ performances with the compositions of the cinematographer, while managing all of the other minutiae that one must deal with on a set, will be key to the success of your project. Central to all of the above is the ability to use the camera.

The camera is the primary piece of equipment in any type of production, so in this chapter, you’re going to get familiar with your camera. Professional cinematographers know their cameras inside and out. Many of them will only work with certain types of cameras, and some will only work with equipment from specific rental houses. The advantage of most digital video cameras is that you can point and shoot and still get a good image. However, if you want to get the most from your camera, you should follow the example of the pros and take the time to learn the details of your gear.

In Chapter 4, “Choosing a Camera,” we explained how digital video cameras work, in Chapter 5, “Planning Your Shoot,” we discussed different types of shots. In this chapter, we’ll show you how to use the various features of a typical film or video camera and we’ll discuss how to put it all together using exposure, strong compositions, and camera movement to tell your story.

Shooting good footage involves much more than simply knowing what button to push and when. There are many creative decisions involved in setting up your shots, and in this chapter, we’re going to cover all of the controls at your disposal and learn how they affect your final image.

Shooting with DSLRs

Shooting HD video with still cameras differs significantly from shooting with “normal” video cameras. We discuss shooting with DSLRs in detail in Chapter 10 “DSLRs and Other Advanced Shooting Situations.”

Setting Focus

Focus is possibly the most basic part of using a camera. All modern cameras come with autofocus mechanisms, but in order to truly master the camera, you need to learn how to set and control the focus yourself.

Before you can focus your camera, make sure the viewfinder is adjusted to match your vision. Most cameras, like the ones in Figures 7.1 and 7.2, have an adjustment ring, or diopter, on the viewfinder. (Refer to your camera documentation for specifics.) Set the camera lens out of focus, then look through the viewfinder and move the viewfinder focus adjustment until you can see the grains of glass or the display information in the viewfinder itself.

144 The Digital Filmmaking Handbook, 4E

Figure 7.1

A typical entry-level professional camcorder from Sony.

Figure 7.2

Typical features of a professionallevel shoulder-mount camcorder.

Chapter 7 n Using the Camera |

145 |

If your camera allows, turn off the auto-focus mechanism. Auto focus will always focus on the middle of the frame. Since you might want to be more creative than this, stick with manual focus.

To focus a zoom lens manually, zoom all the way in to your subject and focus the image. Now you can zoom back to compose the shot at the focal length you desire. As long as your subject doesn’t move forward or backward, your image will be in focus at any focal length available.

Many video cameras have a special focus assist view that displays a zoomed in portion of the frame so that you can double-check the focus. This is especially helpful if you do not have a field monitor (see Figure 7.3)

You can also focus by composing your shot first and then adjusting the focus ring on the lens, the same way you would with a prime lens. The only problem with this method is that the wider your shot, the harder it will be to tell if your subject is truly in focus and if the subject or camera moves, you will have to make an adjustment to keep the shot in focus.

Figure 7.3

The focus assist button makes it easier to check focus on the fly.

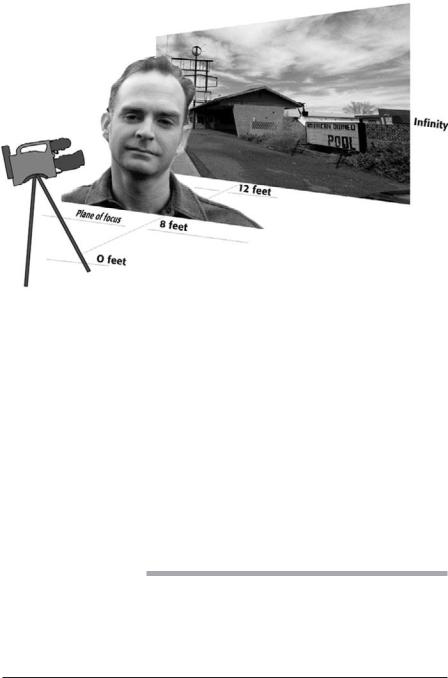

Luckily, most images have a depth of field that exceeds the depth of focus. In Figure 7.4, the depth of focus is eight feet from the camera, but the depth of field—the part of the image that appears in focus—starts a couple of feet in front of the subject and extends to infinity. Anything behind the subject will appear in focus, even though it is not on the plane of focus.

If you’re having trouble focusing, use your manual iris control to iris down (go to a higher f-stop number). This will increase your depth of field and improve your chances of shooting focused. Under most normal, bright lighting conditions, especially daylight, the field of focus will extend from your subject (the plane of focus) to infinity (see Figure 7.4).

146 The Digital Filmmaking Handbook, 4E

Figure 7.4

In this illustration, the plane of focus is eight feet from the lens, but the depth of field is much bigger. Everything behind the plane of focus appears in focus as well.

Generally, focus won’t present much of a problem. In fact, one of the biggest complaints about the look of digital video is that the focus is too sharp throughout the image. Film typically has a much more shallow depth of field than video, so often only the subject is in focus (see Figure 7.13). One way to get more of a film-like image is to control the lighting and exposure so that the depth of field is shallow. With a video camera, this is very difficult to do under bright, uncontrolled lighting conditions such as daylight. (More about how to get shallow depth of field in Chapter 10.)

The only time you’re likely to encounter a focus problem is when you’re shooting in low-light conditions. When there isn’t a lot of light, the field of focus becomes very small, and it’s hard to judge focus in the viewfinder or LCD display when there isn’t much light on the subject.

If focus is critical and the lighting conditions are challenging, the only way to be absolutely sure that your shot is in focus is to measure the focus with a tape measure and then change, or “pull” the focus on the lens as the camera or subject moves. We explain how to measure and pull focus in Chapter 10.

Use a Field Monitor

Feature film directors connect “video assist” monitors to their 35mm film cameras so that they can see what the camera operator sees through the viewfinder. A field monitor lets you do the same thing with a video camera. Even if you’ll be operating the camera yourself, a field monitor can be an asset, making it much easier to focus and frame your shots, and it lets others see what the camera operator is seeing. To see a true HD image, you’ll need to use the HD output on the camera and the HD input on the monitor. (For more on monitoring video on the set, see Chapter 10.)