Scheer Solar Economy Renewable Energy for a Sustainable Global Future (Earthscan, 2005)

.pdfEXPLOITING SOLAR ENERGY 273

Any responsible local councillor with a clear understanding of these possibilities should feel obliged to set this process in train, which means above all regaining or retaining control of local supply networks and pushing the integration of energy functions to the top of the local political agenda. The result would be more jobs for local people and a stronger local economy.

The path I describe leads from external supply to regional, municipal and individual self-sufficiency. For many individuals, this will mean autonomous energy supplies; for society it means no long-distance power cables, apart from the few lines needed to bring power from large dams and windfarms. As the centralized gas and electricity industry loses its purpose, and municipal power supplies and energy self-sufficiency expand into more and more domains, the highand medium-voltage cables will gradually disappear. Pylons will no longer march across the landscape, more than compensating for any decline in landscape quality due to wind turbines. The big energy suppliers would dismantle the pylons themselves, as the maintenance costs would no longer be worth their limited use. Private operators of PV, wind, hydro and biogas plants will – supported by grid feed-in laws – either become partners of the municipal energy corporations, which in turn will no longer have difficulty finding customers for their energy, because surpluses can be stored for later use – or they might become direct suppliers of green energy, equipped with their own storage facilities and supplying customers round the clock. Perhaps they will also run garages for vehicles running on electricity, compressed air, fuel cells or hydrogen-driven internal combustion engines.

Just as electricity need no longer be supplied through centrally managed supply chains, so too with motor fuel. This is no utopian vision, but a real possibility: centrally run energy suppliers will always have higher overheads than local suppliers, even with a common distribution infrastructure. Synergies achieved through consolidation cannot achieve the same economic results as a local network, because the latter can deploy storage and conversion technologies far more flexibly and make more imaginative use of its assets. Not least, a local

274 TOWARDS A SOLAR ECONOMY

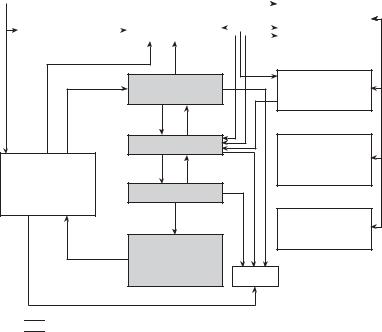

Hierarchical divisions within the conventional energy system between source and consumer

Requires grid-access laws |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central level |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Energy sources, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RS |

|

|

OS + C |

|

|

end-consumers |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

S |

S |

|

C |

C |

C |

CS |

Electr- |

Fuel, |

Fuel, |

|

icity |

oil |

gas |

|

Integrated hierarchical energy supplies – the industry model

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

S + G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Energy sources, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RS |

|

|

OS + C |

|

|

|

C |

|

C |

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CS |

||||||||||

end-consumers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Electr- |

Fuel, |

|

Fuel, |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

icity |

oil |

|

gas |

|

|

||||||||||

Integrated distributed energy supplies using renewable energy |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Energy sources, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RS |

|

|

OS + C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

|

||||||||

end-consumers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: RS = renewable source; OS + C = own supply and consumer; C = consumer; CS = conventional source; S = supplier; G = generation plant

Figure 9.1 Energy supply structures incorporating renewable energy

network has no vested interests or large investments to service. Integrated solar energy self-sufficiency is not susceptible to external interference.

The way to achieve this vision is to use local planning powers to bring all the local supply infrastructure together under one network operating company. Existing municipal power companies that generate electricity and distribute electricity and heat should be broken up into network-operat- ing and energy-supply companies. The latter would provide

EXPLOITING SOLAR ENERGY 275

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On-site generation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and supply by |

|

Independent local |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

households and |

|

|

suppliers of green |

|

|

Grid operator |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

businesses |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

energy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Generation of heat |

Energy-consuming |

|

households and |

|

|

and electricity |

|

|

businesses |

|

|

|

|

|

Energy storage* |

Energy- |

Agriculture and |

|

autonomous |

|

households and |

|

forestry, including |

|

businesses |

bio-gas, fuel and |

Bio-fuel production |

|

pest-deterrent |

|

|

production |

|

|

|

|

Energy- |

|

|

management |

|

Fertilizer and |

contractors |

|

|

|

|

pest-deterrent |

|

|

production and |

Garages |

|

trade |

Note:

Possible roles for a municipal energy holding company

Possible roles for a municipal energy holding company

* Including locally collected organic waste, bio-gasification, hydrogen production

Figure 9.2 Model for the future: municipally/regionally integrated energy supply incorporating renewable energy

electricity, heat and motor fuel, and maintain storage facilities to this end. This structure provides optimum scope for crosssubstitution and multiple asset use. Energy production and supply can become cheap and environmentally benign.

The ability of a local network to meet peak power demands in a cost-effective way offers the greatest scope for taking the wind out of the sails of the established electricity industry. Although established companies can also make use of new storage technologies, the much larger scale of their capital installations makes them that much more costly to upgrade. Their inability to put the waste heat from large power stations to economic use, due to the prohibitive cost of constructing the infrastructure for distributing heat, illustrates the extent of the difficulties these companies face. The basic advantages of decentralized local solutions are much lower infrastructural

276 TOWARDS A SOLAR ECONOMY

costs and the unique ability to expand production in small and manageable modular steps. Figure 9.1 contrasts three basic models for energy supply: the current hierarchical structure of conventional energy supply; the consolidated system that existing companies hope to achieve; and a local integrated network. Figure 9.2 presents the forward-looking model of an integrated municipal network in its economic context. The result is a public–private partnership at the local or regional level which can avoid conflicts over capacity with a fundamental rethink of the market mechanisms, looking towards to a future total energy service industry (Heinz Ossenbrink).14

Creative destruction in the energy industry and the transformation of the resource industry

The transition towards a solar global economy follows a completely different path to that taken by the conventional energy industry. In an age where the conventional energy industry is playing an even larger role, and especially where transnational mergers threaten to make the industry all-power- ful, even many supporters of renewable energy think this unrealistic. The sheer concentrated power overawes political institutions, the public and even environmental activists. Many thus look to cooperation with the energy industry, rather than competition. After all, new initiatives suggest that energy companies are finally getting the message, after years of ignoring and obstructing renewable energy; we still need the grid infrastructure, and their financial capital is urgently needed to bring about the desired environmental sea-change – surely cooperation is the only realistic option?

Arguments that appeal to realism always beg the question: which reality? And whose? Physical laws excepted, all ‘realism’ is a subjective and usually incomplete assessment. It is realistic to note that renewable energy can no longer be ignored, and that energy companies are also beginning to take an interest. It is realistic to see that the fossil energy industry is continuing to expand, and that the trend towards consolidation is accelerating. When dinosaurs mate, their offspring are not pussycats. It is realistic to realize that the scale of the problem makes it

EXPLOITING SOLAR ENERGY 277

irresponsible to continue expanding the renewable energy sector at the current snail’s pace.

Joseph Schumpeter, one of the greatest economists of the 20th century, asserted that economists were making a fundamental error by only looking at data from one point in time, ‘as if there were no past and no future, believing then that they had understood all there was to understand’. The replacement of fossil fuel by renewable energy is what Schumpeter would have described as a ‘process of industrial transition, which inexorably revolutionizes the structure of the economy from within, inexorably destroys the old structure and inexorably creates a new’. This is what he termed ‘creative destruction’.15 However, this process requires larger economic agents than are to be found among the suppliers of renewable energy, now or at any time.

At first, the energy industry confined the renewable energy boat to port; now they are looking to board and take over the cabins. Now that the boat is finally underway, they want to control its speed and have their hands on the tiller. But the way the energy industry is bound up in its own supply chains should lead us to expect it to sound the ‘all-stop’ at the very latest when its own structure comes under threat. At that point, it would only be necessary to keep the industry on board if its expertise were indispensable and if there were no other suitable major players. But there are.

Allies and co-sponsors for renewable energy are to be found in all those industrial sectors that stand to gain from a solar energy supply, and who can scarcely lose. A broad range of enterprises in industry, in the trades (manually skilled selfemployed professions) and in agriculture has an objective interest in helping to shape the transition; it is just that most of them have yet to recognize this subjectively. They underestimate their scope for action and overlook the opportunities to be gained by driving change. In some cases, they would be able to rely on their existing business model with only a few technical adjustments; in some cases, they would even be able to count on their established markets. In other cases, there would be a need to find new markets and customers: companies in the business of supplying large capital installations to

278 TOWARDS A SOLAR ECONOMY

large clients would need to move into supplying smaller installations to a vastly enlarged customer base.

The electrical and electronics industries are just as well placed to leverage renewable energy technology as are suppliers of machinery and plant and the construction materials industry. Car manufacturers can expand their markets by diversifying into motors for distributed solar energy systems with applications well outside the road transport industry. The agricultural machinery industry, which has for years been losing many customers to agricultural business failure, can expect demand for biomass harvesting equipment to breathe new life into their old markets. Manufacturers of large-scale power plants will need to look for new customers, but the vast numbers of micropower installations that will replace the large power stations will allow them to grow their businesses. Suppliers of construction materials will retain their existing markets through the transition to solar materials, but will need to change their suppliers.

There will inevitably be losers: in the oil, gas and coal industries, among manufacturers of extraction and energy transmission plant, and in the ranks of cabling firms and operators of power stations and grid infrastructure. These firms have the option of diversifying, shifting from fossil energy supply to solar cell or wind turbine manufacture, although they have no more aptitude for solar technology than any other industry

– in most cases, probably less. The technological expertise and existing client base of manufacturers of motors, machinery, plant, electrical appliances and construction materials give them a much better chance of becoming a driving force for renewable energy. They are not hampered or trapped by legacy investments in the fossil energy supply chain, and technologists, electronics experts, farmers, civil engineers, architects and craftspeople, meteorologists, biologists and chemists will be of more use to a firm seeking to exploit renewable energy than the knowledge base of the conventional energy industry in geology, extraction and pipeline technology, conventional power stations, high-tension transmission and high-voltage transformers, etc. Once the interest of the technology industry in accessing new markets is taken into account, along with

EXPLOITING SOLAR ENERGY 279

their greater experience in the marketing of smaller technology goods, they can be seen to have more motivation, to be better equipped and therefore have more scope than classical energy companies for succeeding in the solar global economy.

Industry must throw off the physical and intellectual chains that bind it to the energy business, or else squander its greatest opportunity for future success. Only for the existing energy industry will the transition to a solar energy supply mark the end of the road – something that industrialists, like the general public and many political activists, have yet to realize. In a solar-powered future, every industrial business is also an energy business.

The unique role of the chemicals industry was discussed in Chapter 1. Its close functional links with the oil and gas industry explain why it has so far failed to capitalize on the opportunities renewable energy affords it. Yet the contribution of the chemical industry is of central importance to much solar technology – for example, the manufacture of silicon or other solar cell substrates, battery technology, electrochemical and thermochemical energy storage media, insulating materials. Even more significant is the contribution it could make by replacing fossil and mineral raw materials with solar substitutes in, for example, plastics, dyes, paints, varnishes and medicines.

Unlike the energy industry, the chemical industry is not faced with dissolution, and it has certainly developed an acute awareness of new opportunities, as the strong interest in biotechnology shows. Trying to tailor new ventures to fit existing production processes based on fossil resources, however, is a dead end. If the established chemicals industry does not make the leap from fossil hydrocarbons to solar materials, this task will fall to new chemicals enterprises. Tapping not just solar energy, but ultimately the materials potential as well, will lead to a complete shake-up of the supplier base. More and more suppliers will join the existing few as new applications are discovered for ever greater numbers of plants. The result will be a decentralization of the raw materials industry.

As industrial companies come to recognize and capitalize on their opportunities, new alliances will be formed: between electronics and glass, between the building materials and electri-

280 TOWARDS A SOLAR ECONOMY

cal industries and manufacturers of solar collectors and PV, between motor manufacturers and suppliers of chemical equipment. New groupings will form as old alliances dissolve; as the fossil industrial web unravels, so too will the power structures it sustains. Some existing giants will retain their size; some small PV and wind turbine manufacturers will grow to the proportions of today’s car manufacturers. There will be a rash of new specialist biotech enterprises. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, new mass-market technologies have been bringing about economic upheavals – but none compare with the dissolution of the fossil resource base and its global supply chains.

A solar resource base is no impediment to consolidation among manufacturers of solar technologies, but it does rescind the globalization imperative currently driving the resource industry. The transition to a solar resource base will loosen the fossil clamps on the global economy. It also signifies a fundamental turning point in economic history: away from the inexorable trend towards an ever-decreasing pool of megacorporations, and towards sustainable smaller and medium-sized business forms, which will be and must remain embedded within a regional context, and whose business models may even prove more effective than those of large structures. This is the most comprehensive and most significant structural change in the history of the global economy, and thus also the most controversial.

Hard roads to soft resources

Conflict for conflict’s sake is unproductive for all concerned. Consensus for consensus’s sake is a pyrrhic victory. Horses for courses: each may be the appropriate response to a given situation. Social conflict is necessary where illegitimate interests stand in the way of a legitimate, uncontroversial and universally desirable aim. Consensus must be sought where common ground can be found between the aspirations and interests of different groups, or if conflict between them would drag in the entirety of society, including disinterested third parties.

Unfortunately, it is entirely legal to exploit resources whose processing imposes hefty burdens on society and disrupts

EXPLOITING SOLAR ENERGY 281

ecosystems. It would even be legitimate, if there were no other way to satisfy the material needs of humanity. But the existence of other possibilities has collapsed the social legitimacy of the nuclear and fossil energy industry. At the very latest, this will be abundantly clear to the next generation. Continuing to cling to the current system without good cause will render conflict over the introduction of solar alternatives inevitable. Any consensus that postpones the shift away from fossil fuels in order to protect established interests does untold damage to society, whereas conflicts that advance the alternative are beneficial – even if not always to the individual protagonists.

There is not even any need to pick a fight with the nuclear and fossil fuel industry: it is already happening, with a stream of new offensives from the major agents in the industry, from international conflicts over access to resources, through to systematic attempts to block successful initiatives to build a market for renewable energy. Calls from the energy industry to seek consensus whenever their interests are threatened are pure hypocrisy.

The question is thus not whether conflict is to be desired, but whether proponents of alternatives to the nuclear and fossil fuel resource industry themselves recognize and have the courage for the existing conflict. Just how doggedly the apologists of the conventional energy industry are prosecuting this conflict can be seen in the innumerable reports and announcements portraying a distorted picture of renewable energy and the state of the technology, not infrequently produced with the aid of generously remunerated scientists. The aim is to create the impression that currently insuperable technical or economic factors militate against rapid change in the energy sector, so that the public will continue to put up with the current state of affairs, despite appreciating the resultant acute dangers.

We must therefore make it our job to expose the real motives for the reluctance to take renewable energy on board – and already we are in the thick of conflict, because the interests of the energy complex are dressed up as seemingly objective constraints. Even pointing out highly subjective interests is characterized as ‘lacking objectivity’ and is treated as an attack. But as Karl Jaspers said, one must ‘say what is, and do what

282 TOWARDS A SOLAR ECONOMY

must be’. Problems only become insoluble if even the possibility of a solution is subject to a conspiracy of silence.

So the electricity industry is virtually unopposed in its circumvention of new electricity market regulations requiring transparent separation between production, transmission and distribution. The long-overdue, hard-nosed response would be to put enforced functional separation on the political agenda, with the clear objective of placing at least the local gas and electricity distribution grids under municipal control, handing the medium-voltage grids over to the state, regional or county authorities, and bringing the national high-voltage backbone under the control of the national government, just as with the road network. The provision and maintenance of public infrastructure is no job for the private sector. When it comes to the privatization of public energy utilities, it ought to go without saying that only the power stations should be sold, and not the grids. This is the path that Italy has followed: privatization of the power stations, with the grids remaining in public ownership. This is a battle we must dare to fight.

It has only recently become public knowledge that German manufacturers of electricity cables have been colluding on prices for almost a century, creaming off billions of marks in the process. The case resulted in a fine of several hundred million marks. But what about the vastly exaggerated prices charged by the German electricity industry during the era of regional monopolies? It is becoming clear that that must have been the case, otherwise the newly privatized companies would not have been in a position to deliver instant price cuts of 20 per cent and more. The excess profits of municipal energy utilities were passed on to the municipal authority, and used to finance local services. The electricity companies, on the other hand, played Monopoly with the economy, building up capital reserves which now represent a strategic resource in the battle for the end-consumer against independent municipal utilities, the aim being to sweep both them and their more efficient local CHP capacity from the market. The current financial muscle of the electricity companies is evidence of the extent to which they have been leading the regulatory authorities up the garden path over recent decades, in order to secure approval for