- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

|

64 |

|

MENTAL ACCOUNTING |

25 percent fat, framing the potato chips as being relatively unhealthy. By increasing the discount on the three-bag deal for the 75 percent fat-free potato chips, the percentage of participants purchasing the three-bag deal increased by more than 40 percent. Decreasing the price of the deal for the 25 percent fat chips increased the percentage of participants taking the three-bag deal by only about 10 percent. Thus, those viewing the potato chips as a more-virtuous item were more price sensitive than those viewing it as more of a tempting item. This may be explained by people setting a limit on the number of bags of fatty potato chips they will take given the temptation to consume them once they are purchased. On the other hand, the more-virtuous chips might not be considered a temptation because people don’t believe they will have the same negative future consequences. Thus, they do not face the same budget constraint.

Rational Choice over Time

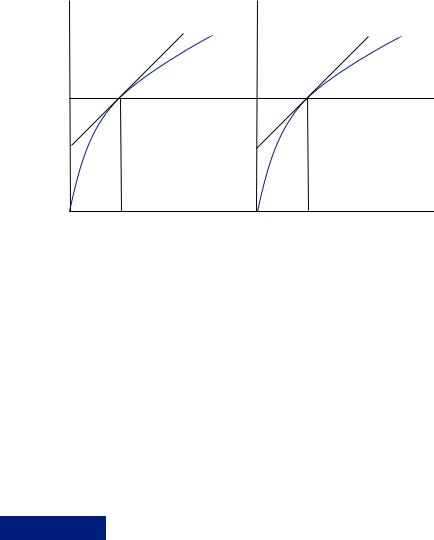

Some of the important predictions of mental accounting deal with how people trade off consumption choices over time. Temptation and self-control issues are just one example. Rational models of consumption over time assume that people are forward looking and try to smooth consumption over time. For example, a typical model of consumer choice over time may be written as

|

T |

δtu ct |

|

max |

|

3 10 |

|

T |

t = |

1 |

|

ct t = 1 |

|

subject to

T |

|

T |

|

|

|

ct < w + |

|

yt, |

3 11 |

t = |

1 |

t = |

1 |

|

where u represents the instantaneous utility of consumption in any period, δ represents the discount factor applied to future consumption and compounded each period, ct represents consumption in period t, yt represents income in period t, w represents some initial endowment of wealth, and T represents the end of the planning horizon—when the person expects to die. Equation 3.11 requires that consumers cannot spend more than their wealth plus the amount they can borrow against future earnings in any period. This model can be used to model how a windfall gain in wealth should be spent. Generally, the model shows that people should smooth consumption over time. Thus, if you suddenly come into some unexpected money, this money is incorporated into your income wealth equation (3.11) and will be distributed relatively evenly across consumption in future periods (though declining over time owing to the discount on future consumption).

As a simple example, consider a two-period model, T = 2, with no time discounting, δ = 1. As with all consumer problems, the consumer optimizes by setting the marginal utility divided by the cost of consumption equal across activities. In this case, the two activities are consumption in period 1 and consumption in period 2. Because the utility

|

|

|

|

Rational Choice over Time |

|

65 |

|

u(c1)

u(c1*) = u(c2*)

u(c2)

u(c1) |

u(c2) |

|

|

|

FIGURE 3.9 |

c1* |

|

c2* |

Two-Period Consumption |

c1 |

c2 Model without Discounting |

derived from each activity is described by the same curve, u

, and because the cost of consumption is assumed to be equal across periods, this occurs where c1 = c2. Figure 3.9 depicts the cost of consumption using the two tangent lines with slope of 1. Thus, any amount received unanticipated would be divided between the two periods equally. Similarly, any anticipated income is distributed equally throughout the future consumption periods. Discounting modifies only slightly, with the marginal utility in the second period multiplied by the discount factor being equal to the marginal utility in the first period. So long as δ is relatively close to 1, the income should be distributed very near equality.

, and because the cost of consumption is assumed to be equal across periods, this occurs where c1 = c2. Figure 3.9 depicts the cost of consumption using the two tangent lines with slope of 1. Thus, any amount received unanticipated would be divided between the two periods equally. Similarly, any anticipated income is distributed equally throughout the future consumption periods. Discounting modifies only slightly, with the marginal utility in the second period multiplied by the discount factor being equal to the marginal utility in the first period. So long as δ is relatively close to 1, the income should be distributed very near equality.

The optimum occurs where δi u

u ci

ci

ci = δj

ci = δj u

u cj

cj

cj for every period j and i. Thus marginal utility should increase by a factor of 1

cj for every period j and i. Thus marginal utility should increase by a factor of 1 δ each period, and as marginal utility increases, consumption declines owing to diminishing marginal utility. An unexpected gain in wealth should be distributed just as an expected gain: nearly evenly among all future consumption periods but at a rate that declines over time.

δ each period, and as marginal utility increases, consumption declines owing to diminishing marginal utility. An unexpected gain in wealth should be distributed just as an expected gain: nearly evenly among all future consumption periods but at a rate that declines over time.

EXAMPLE 3.7 Windfall Gains

Whether money is anticipated or comes as a surprise, traditional theory suggests that people should optimize by spending their marginal dollar on the activity with the highest return. Behavioral economists have studied the impact of unanticipated money, or windfall gains, on spending behavior. Experimental evidence suggests that people might have a greater propensity to spend money that comes as a surprise than money that is anticipated.

Hal Arkes and a team of other researchers recruited 66 undergraduate men to participate in the experiment. Participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire, go to an indoor stadium to watch a varsity basketball game, and then return to fill out a second questionnaire. All of the participants were given $5 before they attended the basketball game. Some were told that they would receive the money, and others were not. Participants were asked to report how much money they had spent at the concession stands

|

|

|

|

|

66 |

|

MENTAL ACCOUNTING |

during the game. Those who had anticipated being paid spent less than half as much at the basketball game on average. Thus those who had known they would receive the money were much less likely to spend the money impulsively.

Mental accounting provides one possible explanation for this activity. For example, anticipated income may be placed in a mental account designated for certain purchases and budgeted already when received. Unanticipated money may be entered into a separate account specifically for unanticipated income and designated for more frivolous or impulsive purchases. Thus, whether the money is anticipated or not determines which budget the money enters, and it thus determines the level of marginal utility necessary to justify a purchase, as in Figure 3.4. Presumably in this case, people have allocated more than the overall optimal amount to their impulse budget and less than the overall optimal amount to their planned spending budget. Thus, the propensity to spend out of the impulse budget is much higher than out of the planned-spending budget.

Rational Explanations for Source-Based

Consumption and Application

Little work has been done to reconcile mental accounting–based behavior with the rational choice model. However, the mental accounting model is based on the methods of accounting employed by major corporations. These corporations have many resources and many activities. It is relatively difficult for central decision makers in these organizations to keep track of all the various activities in order to make informed decisions. The method of accounting, including the keeping of separate accounts and budgets for various activities, has been developed as a method of keeping track of expenses and capital. This may be thought of as a response to mental costs of trying to optimize generally. Instead of considering all possible activities and income sources at once, breaking it down into components might simplify the problem and allow manageable decisions. People might face similar problems in managing their own purchasing and income decisions. Hundreds of decisions are made each day. To optimize generally would be too costly. Perhaps the loss in well-being for using mental accounts is less than the cost of carrying out general optimization over all decisions.

With respect to marketing, mental accounting suggests that how you categorize your product and how you frame purchasing decisions does matter. In selling products that require repeated expenditure, you may be able to increase sales of the item by framing these continued expenses so as to aggregate them in the minds of consumers. Additionally, segregating the gains can induce greater sales. This could explain the late-night infomercials that meticulously describe each item they are selling in a single package, asking after each new item, “Now how much would you pay?” The use of prepayment for single-consumption items might induce greater sales than offering consumer financing alone. Additionally, goods that receive repeated use may be more easily sold with financing that amortizes the costs over the life of the product. Clever use of mental accounting principles can induce sales without significant cost to a producer.

To the extent that people suffer from self-control problems, using budget mechanisms may be an effective tool. If self-control is not an explicit issue, budgets should be set to

|

|

|

|

Rational Explanations for Source-Based Consumption and Application |

|

67 |

|

maximize the enjoyment from consumption over time. More generally, people who behave according to mental accounting heuristics can potentially improve their wellbeing by reevaluating their spending budgets regularly, cutting budgets for categories for which the marginal utility is low relative to others.

Much like the rest of behavioral economics, mental accounting can seem to be a loose collection of heuristics. By spurning the systematic overarching model of behavior embodied by traditional economics, behavioral economics often provides a less-than- systematic alternative. In particular, mental accounting combines elements of prospect theory, double-entry accounting, and mental budgets to describe a wide set of behaviors. To the extent that these behaviors are widespread and predictable, this collection is useful in modeling and predicting economic behavior. One of the most pervasive and systematic sets of behaviors documented by behavioral economists is loss aversion.

Behavioral economics is eclectic and somewhat piecemeal. Loss aversion is the closest thing to a unifying theory proposed by behavioral economics. The notion that people experience diminishing marginal utility of gains and diminishing marginal pain from losses, as well as greater marginal pain from loss than marginal pleasure from gain, can be used to explain a wide variety of behaviors. In the framework of mental accounting, loss aversion provides much of the punch. Loss aversion is discussed further in many subsequent chapters.

Biographical Note

Courtesy of George Loewenstein

George F. Loewenstein (1955–)

B.A., Brandeis University, 1977; Ph.D. Yale University, 1985; held faculty positions at the University of Chicago and Carnegie Mellon University

George Loewenstein received his bachelor’s degree and Ph.D. in economics. He helped lay the foundation for incorporating psychological effects in the economics literature on intertemporal choice. He has also made contributions to mental

accounting, inconsistent preferences, predictions of preferences, and neuroeconomics. His foundational work recognizes that the state of the person can affect how the person perceives an event. Further, people have a difficult time anticipating how changes in their state might affect decision making. For example, a person who is not hungry might not be able to anticipate a lower level of resistance to temptation in some future hungry state. Such changes in visceral factors can lead people to expose themselves to overwhelming temptation, potentially leading to risky choices regarding drinking, drug use, or sexual behavior. More recently, his work on neuroeconomics, a field using brain imaging to map decision processes, has found support for the notion that people use separate processes to evaluate decisions using cash or a credit card. This work may be seen as validating at least a portion of the mental accounting framework. His groundbreaking work has resulted in his being named a fellow of the American Psychological Society and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

|

|

|

|

|

68 |

|

MENTAL ACCOUNTING |

T H O U G H T Q U E S T I O N S

1.Consider a high school student who is given $3 every school day by her parents as “lunch money.” The student works a part time job after school, earning a small amount of “spending cash.” In addition to her lunch money, the student spends $5 from her own earnings each week on lunch. Suppose her parents reduced her lunch money by $2 per day but that she simultaneously receives a $10-per-week raise at her job, requiring no extra effort on her part. What would the rational choice model suggest should happen to her spending on lunch? Alternatively, what does the mental accounting framework predict?

2.Suppose you manage a team of employees who manufacture widgets. You know that profits depend heavily on the number of widgets produced and on the quality of those widgets. You decide to induce better performance in your team members by providing a system of pay bonuses for good behavior and pay penalties for bad behavior. How might hedonic framing be used to make the system of rewards and penalties more effective? How does this framing differ from the type of segregation and integration suggested by hedonic editing?

3.Suppose you are a government regulator who is concerned with the disposition effect and its potential impact on wealth creation. What types of policies could be implemented to reduce the sale of winning stocks and increase the sale of losing stocks? The government currently provides a tax break for the sale of stocks at a loss. This tax break tends to encourage the sale of losing stocks only in December. What sorts of policies could encourage more regular sales of losing stocks?

4.You are considering buying gifts for a pair of friends. Both truly enjoy video gaming. However, both have reduced their budget on these items because of the temptation that they can cause. Dana is tempted to buy expensive games when they are first on the market rather than waiting to purchase the games once prices are lower. Thus, Dana has limited himself only to purchase games that cost less than $35. Alternatively, Avery is tempted to play video games for long periods of time, neglecting other important responsibilities. Thus, Avery has limited herself to playing video games only when at other people’s homes. Would Dana be better off receiving a new game that costs $70 or a gift of $70 cash? Would Avery be better off receiving a

video game or an equivalent amount of cash? Why might these answers differ?

5.Suppose Akira has two sources of income. Anticipated income, y1 is spent on healthy food, represented by x1, and clothing, x2. Unanticipated income, y2 is spent on dessert items, x3. Suppose the value function is given

1

by v x1, x2, x3 = x1x2x3 3 , so that marginal utility of

good 1 is given by |

v x |

, x |

, x |

|

= 1 x |

− |

2 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1 |

3 |

x2x3 |

3 , marginal |

|||||||||||

|

|

x1 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

utility |

for good |

2 |

is |

|

v x1 , x2, x3 |

= |

1 x − |

2 |

|

1 |

|

|

||||||

|

3 |

|

x1x3 3, |

and |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x2 |

|

|

3 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

marginal |

utility |

of |

good |

3 |

is given |

by |

|

|

v x1, x2, x3 |

|

= |

|||||||

|

|

x3 |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

− 2 |

x1x2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31 x3 3 |

3. Suppose y1 = 8 and y2 |

= 2, and that the |

||||||||||||||||

price of the goods is given by p1 = 1, p2 = 1, p3 = 2. What is the consumption level observed given the budgets? To find this, set the marginal utility of consumption to be equal for all goods in the same budget, and impose that the cost of all goods in that budget be equal to the budget constraint. Suppose Akira receives an extra $4 in anticipated income, y1 = 12 and y2 = 2; how does consumption change? Suppose alternatively that Akira receives the extra $4 as unanticipated income, y1 = 8 and y2 = 6; how does consumption change? What consumption bundle would maximize utility? Which budget is set too low?

6.Consider the problem of gym attendance as presented

in |

this chapter, where Jamie perceives the value |

||

of |

attending |

the gym |

to be va xn − pδt n + |

vt |

− pδt + pr n |

, where xn |

is the monetary value to |

Jamie of experiencing the n th single attendance event at the gym, p is the price paid once every six months, δ is the monthly rate of depreciation, t is the number of months since the last payment was made, n is the number of times Jamie has attended the gym since paying, including the attendance event under consideration, and pr n

n is the price Jamie considers fair for attending the gym n times. Suppose that the cost of gym membership is $25. Further, suppose Jamie considered the value of attending the gym n times in a sixmonth window to be va

is the price Jamie considers fair for attending the gym n times. Suppose that the cost of gym membership is $25. Further, suppose Jamie considered the value of attending the gym n times in a sixmonth window to be va n

n = 5n − n2 − δt25

= 5n − n2 − δt25 n. Also, suppose that Jamie considers the fair price for a visit

n. Also, suppose that Jamie considers the fair price for a visit

to |

be $4, so the |

transaction utility is equal to |

vt |

n = − 25δt + 4n. |

Payments depreciate at a rate of |

δ = .5. Determine the number of visits necessary in each of the six months in order to obtain a positive account. How much time would have to pass before only a single visit could close the account in the black?