- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

|

420 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

Inequity Aversion

One might have several potential motivations for rejecting a low offer. However, the correct explanation seems likely to involve other-regarding preferences in some way. One proposal put forward by Ernst Fehr and Klaus Schmidt is that people tend to want outcomes to be equitable. In this case, people might try to behave so as to equalize the payoffs between themselves and others. Thus, if Player 1’s monetary payout is lower than others’ in the game, Player 2 will behave altruistically toward Player 1. Alternatively, if Player 1’s monetary payout is larger than others’ in the game, Player 2 will behave spitefully. Players are spiteful if they behave so as to damage another player even if it requires a reduction in their own payout. We refer to preferences that display this dichotomy of behaviors (altruistic to the poor, spiteful to the rich) as being inequity averse. A simple example of inequity-averse preferences is represented where player i maximizes utility given by

U x1, x2, , xn |

= xi − |

α |

|

max xj − xi, 0 − |

βi |

|

max xi − xj, 0 |

n − 1 |

|

n − 1 |

|

||||

|

|

j i |

|

j |

i |

||

|

|

|

|

|

15

15 1

1

and where xi is the monetary payoff to player i, n is the total number of players, and α and βi are positive-valued parameters. Here α represents the disutility felt by the decision maker whenever others receive a higher payout than he does (perhaps due to jealousy), and βi represents the disutility felt by the decision maker whenever he receives a higher payout than some other player does (perhaps due to sympathy). In this case, players decide whether they will be spiteful or altruistic toward any one player based upon whether that player receives more or less from their payout. Thus, behavior motivated by inequity aversion is much like the notion of positional externalities discussed in Chapter 14.

Preferences such as those represented in equation 15.1 are easily applied to twoplayer games such as the dictator and ultimatum games we have used as examples. For example, consider the dictator game in which a dictator is called upon to divide $10

between himself and a peer. In this case, the problem can be represented as |

|

maxx 0,10 x − α max 10 − 2x, 0 − β max 2x − 10, 0 , |

15 2 |

where x is the amount the dictator receives and 10 − x is the amount the other player receives. Thus, the difference between the payout to the dictator and the other player is x −  10 − x

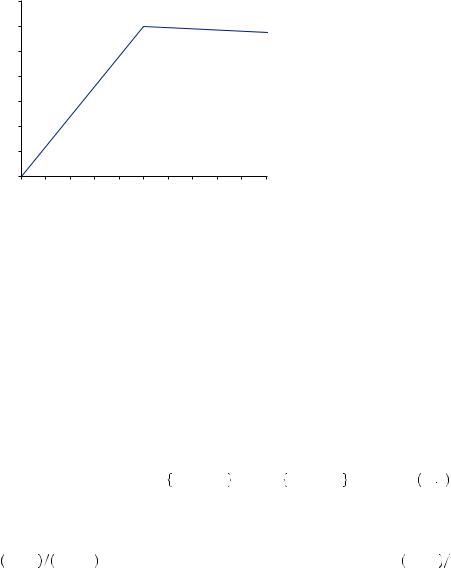

10 − x = 2x − 10. One example of this utility function is displayed in Figure 15.1 (with α = 0.7 and β = 0.6). If the dictator takes $5, then the value of the second two terms in equation 15.2 are zero, and the dictator receives utility of 5. If, instead, the dictator takes any more than $5, the utility function has a slope of 1 − 2β. If the dictator takes less than $5, then the utility function has a slope of 1 + 2α. If β < 0.5, then the utility function will be positively sloped everywhere, and the dictator will choose to take all the money. If β > 0.5, then the utility function will be negatively sloped above $5, and the dictator would only ever take $5.

= 2x − 10. One example of this utility function is displayed in Figure 15.1 (with α = 0.7 and β = 0.6). If the dictator takes $5, then the value of the second two terms in equation 15.2 are zero, and the dictator receives utility of 5. If, instead, the dictator takes any more than $5, the utility function has a slope of 1 − 2β. If the dictator takes less than $5, then the utility function has a slope of 1 + 2α. If β < 0.5, then the utility function will be positively sloped everywhere, and the dictator will choose to take all the money. If β > 0.5, then the utility function will be negatively sloped above $5, and the dictator would only ever take $5.

|

|

|

|

Inequity Aversion |

|

421 |

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Utility |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$0 |

$1 |

$2 |

$3 |

$4 |

$5 |

$6 |

$7 |

$8 |

$9 |

$10 |

Dictator’s payoff

FIGURE 15.1

Inequity-Averse Preferences in the Dictator Game

Inequity-averse preferences are also instructive in considering the ultimatum game. To find the SPNE, let us first consider the second player’s decision. Given that Player 1 chooses to allocate x to himself and 10 − x to Player 2, Player 2 then faces the choice of whether to accept or reject the offer. Player 2 thus solves

maxh 0,1

0,1

h ×

h ×  10 − x − α2 max

10 − x − α2 max 2x − 10, 0

2x − 10, 0 − β2max

− β2max 10 − 2x, 0

10 − 2x, 0 +

+  1 − h

1 − h ×

×  0

0 ,

,  15

15 3

3

where h is the choice variable, equal to 1 if Player 2 accepts the offer and equal to 0 if Player 2 rejects it, and subscript 2 indicates the parameters of Player 2’s utility function. The first term in the braces represents the utility gained from accepting the offer, and the second term (which is always 0) is the utility of rejecting the offer. Player 2 will thus reject the offer if the utility of accepting is less than 0, or if

10 − x < α2max 2x − 10, 0 + β2max 10 − 2x, 0 . |

15 4 |

In other words, Player 2 should reject the offer if the offer falls below some threshold level defined by Player 2’s preferences. If, for example, we only consider offers that

give Player |

2 less |

than Player 1, Player 2 |

will reject |

if the offer 10 − x < 10 − |

10 α2 + 1 |

1 + 2α2 |

. This corresponds to |

Player 1’s |

receiving x > 10 α2 + 1 |

1 + 2α2

1 + 2α2 . Falling below this threshold would represent a split that was so unequal that Player 2 would prefer everyone to receive nothing. Thus, an inequity-averse person might decide to reject an offer from Player 1, even if the offer would provide Player 2 more money than rejecting the offer.

. Falling below this threshold would represent a split that was so unequal that Player 2 would prefer everyone to receive nothing. Thus, an inequity-averse person might decide to reject an offer from Player 1, even if the offer would provide Player 2 more money than rejecting the offer.

To find the SPNE strategy for Player 1, consider the choice of Player 1 in the first stage of the game. If Player 1 is inequity averse, then his decision will be much like that in the dictator game. So long as Player 1 offers an amount to Player 2 that is greater than10 − 10 α2 + 1

α2 + 1

1 + 2α2

1 + 2α2 , Player 2 will accept. Player 1 must thus solve equation 15.2 subject to the constraint x < 10

, Player 2 will accept. Player 1 must thus solve equation 15.2 subject to the constraint x < 10 α2 + 1

α2 + 1

1 + 2α2

1 + 2α2 . If Player 1 takes $5, then the

. If Player 1 takes $5, then the

|

|

|

|

|

422 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

value of the second two terms in equation 15.2 is zero, and Player 1 receives utility of 5. If the dictator takes any more than $5, the utility function has a slope of 1 − 2β1. If the dictator takes less than $5, then the utility function has a slope of 1 + 2α1. Thus, Player 1 will never take less than $5 unless Player 2 would decide to reject this offer. However, given the functional form for the utility function, Player 2 would never reject this offer (it yields utility of 5 > 0 for both). If the parameter of Player 1’s utility function β1 < 0.5, then the utility function will be positively sloped everywhere. In this case, Player 1 will choose the allocation that gives Player 1 the most money without Player 2 rejecting. Thus Player 1 would choose the largest x such that x < 10 α2 + 1

α2 + 1

1 + 2α2

1 + 2α2 . This occurs where

. This occurs where

x = 10 |

α2 + 1 |

. |

15 5 |

|

|||

|

1 + 2α2 |

|

|

Thus, the more-averse Player 2 is to obtaining less than Player 1, the greater the offer to Player 2, with a maximum value of 5 as α2 goes to infinity. If β1 > 0.5, then the utility function is negatively sloped above $5, and Player 1 would only ever take $5 in the first stage.

Clearly, this is a very restrictive theory, and it cannot fully explain all of the various behaviors we observe, particularly in the dictator game. Many of the outcomes of the dictator game have the dictator taking something between $5 and $10—an outcome excluded by this model. However, this simple model clearly communicates the idea that people might have an aversion to unequal distributions of payouts. More-general models have been built on the same ideal (e.g., by allowing increasing marginal disutility of inequality) that would potentially explain more of the various outcomes observed in the dictator game.

EXAMPLE 15.2 Millionaires and Billionaires

Inequity aversion often finds its way into political discourse. In 2011, facing mounting deficits, the United States faced the possibility of a downgrade in its credit rating. If reduction of a budget deficit is the primary goal, there are only two ways to reach it: raise revenues (primarily through taxes) or reduce spending (primarily by cutting social programs). Major disagreements formed over whether to focus more on raising taxes or on lowering expenditures. President Barack Obama argued that raising taxes on the rich would be a reasonable way to proceed. In a speech, he argued that the wealthy receive much of their income through capital gains, which are taxed at a low 15 percent relative to income. Income could be taxed up to 35 percent for higher income earners. This leads to a situation where those making the most money might actually pay a lower tax on overall income than those who obtain most or all of their income through salaried employment. Referring to the iconic billionaire investor, he protested, “Warren Buffett’s secretary should not pay a higher tax rate than Warren Buffett.” The president continually argued for increases in taxes on millionaires and billionaires. “It’s only right that we should ask everyone to pay their fair share.” Moreover, he pointed out that cutting spending would hurt the poor, who have the least to give.

|

|

|

|

Inequity Aversion |

|

423 |

|

On the other side of the aisle, many members of Congress argued that the rich were paying more than their fair share relative to the poor. They argued that a majority of overall tax revenues were taken from the relatively tiny percentage of people in the United States who could be considered wealthy. The top 10 percent of earners accounted for 46 percent of income but paid more than 70 percent of total income taxes. This group included those earning $104,000 and above, far short of the “millionaire and billionaire” image the President portrayed. By many measures, it is the group of earners in a range from $250,000 to $400,000 who face the highest tax burden of any in the country—a group that the President was targeting with tax increases. Instead, others prefer cutting spending that, among other things, goes to the poor, who often face no income tax burden but who benefit from these social programs.

It is perhaps not surprising that both sides could look at the same statistics and come to far different conclusions. Of note, however, is how both sides cloak their arguments in terms of inequity. One side claims that increasing tax rates for the wealthy is necessary to make outcomes equal. The other claims that taxes on the wealthy are already too high and that equity requires that spending on the poor be cut. Neither seems to question the desirability of equity in their arguments, perhaps because they are pandering to an inequity-averse electorate. Often the perception of what is an equitable division of the spoils depends upon how the spoils are framed.

Consider the experiments conducted by Alvin Roth and Keith Murnighan examining how information can influence bargaining. In their experiment, two players were given a number of lottery tickets and were given a certain amount of time to come to an agreement about how to divide the tickets. The proportion of lottery tickets held by a player determined their chance of winning a prize. So having 50 percent of the tickets would result in a 50 percent chance of winning a prize. If no agreement was reached before time ran out, no one would receive lottery tickets. One player would win $5 if one of his lottery tickets paid off, and the other player would win $20 if one of his tickets paid off. Players were always informed of what their own payoff would be should they win, but players were not always informed of their opponents’ payoff. Interestingly, when the $5 player was unaware of the payoff to the other player, players often agreed to a division of lottery tickets that was very close to 50/50. If instead the $5 player knew the other player would receive $20 for a win, the division of lottery tickets was much closer to 80/20 in favor of the $5 player. In this case, without the information about unequal payoffs, equal probabilities looks like a fair deal. However, once one knows that payoffs are unequal, probabilities that are unequal now look more attractive. The sharing rule is influenced by how inequality is framed.

One possible explanation of the difference between the two sides of our tax and spend debate is self-serving bias. Thus comparing income tax and capital gains taxes and comparing those in the middle class to those who make billions a year makes perfect sense if your goal is to increase the consumption of the poor relative to the ultrawealthy. Alternatively, comparing income tax rates of the mid-upper income ranges to income taxes by those in poverty—and particularly those on welfare rolls—might make sense if your goal is to maintain consumption of the upper-middle class.

In essence, people tend to bias their opinion of what is fair or equitable to favor their own consumption. For example, Linda Babcock, George Loewenstein, Samuel Issacharoff, and Colin Camerer gave a series of participants a description based on court testimony from an automobile accident. Participants were then assigned roles in the case and given the

|

|

|

|

|

424 |

|

FAIRNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL GAMES |

opportunity to try to negotiate a settlement, with participants receiving $1 for every thousand dollars of the settlement. They were given 30 minutes to negotiate a settlement in which a fixed amount of money would be divided among them. If they could not reach an agreement, then the actual judgment made in court would be enforced. Some, however, were assigned roles before they read the court testimony, and others were assigned roles only after they had read the court testimony. Those who did not know their roles were able to reach a settlement 22 percent more often than those who knew their roles while reading. This suggests that those who did not know their roles took a more-objective approach to understanding the details of the case than those who had been assigned a role to argue. Once we have a stake in the game, our perceptions of fairness are skewed toward our own self-interest in a way that can affect our judgment in all business transactions.

EXAMPLE 15.3 Unsettled Settlements

In 2003, American Airlines ended a years-long negotiation with the flight attendants’ union. The flight attendants had been working without a contact for most of a decade. They had been unwilling to yield to American Airlines in the negotiations due to their demand for a large increase in pay. In fact, American Airlines had conceded an increase in pay over the period while negotiations took place, but the increase was much lower than the flight attendants had demanded. Interestingly, the contract the flight attendants finally accepted actually reduced their pay. Why did they finally accept? After the tragic attacks of September 11, the airline industry had been hard hit, and American Airlines was bleeding money. Eventually the flight attendants (and pilots also) made concessions because they wanted to be fair. When American Airlines started to lose money, suddenly the flight attendants believed that American Airlines was being honest when they claimed that pushing the salaries any higher would lead to bankruptcy. The flight attendants’ negotiators felt they were making a sacrifice to help save the company and to make room for a more fair and equitable distribution of the dwindling profits.

Two days after an agreement was reached, news broke that top executives at American Airlines were going to receive large bonus checks and other retention incentives. Immediately the deal was off. The flight attendants were again up in arms. Had this changed the monetary offer to the flight attendants? No. But it led them to feel the executives had been dishonest and greedy. If they were going to be greedy, then the flight attendants would too. Eventually, under extreme pressure, the executives gave back their bonuses. This pacified the flight attendants and other workers who had been irked by the bonuses paid to executives. In the end, the flight attendants were not angry over the $10 billion in concessions and lower salary they had been forced to accept. Instead, they were angry about the tens of millions of dollars given to about 10 executives. Redistributing this money would have made a negligible difference in the salaries of the flight attendants—a couple hundred dollars at most. Nonetheless, they were not about to accept the lower salary unless the executives had to do without their bonuses. Even though the bonuses had made no real difference directly in the profitability of the company, the perception that executives had been greedy and callous nearly bankrupted the company by stirring another costly labor dispute.

In fact, simple inequality aversion has a difficult time explaining many of the behaviors we observe. Armin Falk, Ernst Fehr, and Urs Fischbacher demonstrated this using a