- •Brief Contents

- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Who Should Use this Book

- •Philosophy

- •A Short Word on Experiments

- •Acknowledgments

- •Rational Choice Theory and Rational Modeling

- •Rationality and Demand Curves

- •Bounded Rationality and Model Types

- •References

- •Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

- •Fixed versus Sunk Costs

- •The Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Theory and Reactions to Sunk Cost

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for the Sunk Cost Fallacy

- •Transaction Utility and Flat-Rate Bias

- •Procedural Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •Rational Explanations for Flat-Rate Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Theory and Reference-Dependent Preferences

- •Rational Choice with Income from Varying Sources

- •The Theory of Mental Accounting

- •Budgeting and Consumption Bundles

- •Accounts, Integrating, or Segregating

- •Payment Decoupling, Prepurchase, and Credit Card Purchases

- •Investments and Opening and Closing Accounts

- •Reference Points and Indifference Curves

- •Rational Choice, Temptation and Gifts versus Cash

- •Budgets, Accounts, Temptation, and Gifts

- •Rational Choice over Time

- •References

- •Rational Choice and Default Options

- •Rational Explanations of the Status Quo Bias

- •History and Notes

- •Reference Points, Indifference Curves, and the Consumer Problem

- •An Evolutionary Explanation for Loss Aversion

- •Rational Choice and Getting and Giving Up Goods

- •Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect

- •Rational Explanations for the Endowment Effect

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Bidding in Auctions

- •Procedural Explanations for Overbidding

- •Levels of Rationality

- •Bidding Heuristics and Transparency

- •Rational Bidding under Dutch and First-Price Auctions

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Prices in English, Dutch, and First-Price Auctions

- •Auction with Uncertainty

- •Rational Bidding under Uncertainty

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Multiple Rational Choice with Certainty and Uncertainty

- •The Portfolio Problem

- •Narrow versus Broad Bracketing

- •Bracketing the Portfolio Problem

- •More than the Sum of Its Parts

- •The Utility Function and Risk Aversion

- •Bracketing and Variety

- •Rational Bracketing for Variety

- •Changing Preferences, Adding Up, and Choice Bracketing

- •Addiction and Melioration

- •Narrow Bracketing and Motivation

- •Behavioral Bracketing

- •History and Notes

- •Rational Explanations for Bracketing Behavior

- •Statistical Inference and Information

- •Calibration Exercises

- •Representativeness

- •Conjunction Bias

- •The Law of Small Numbers

- •Conservatism versus Representativeness

- •Availability Heuristic

- •Bias, Bigotry, and Availability

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rational Information Search

- •Risk Aversion and Production

- •Self-Serving Bias

- •Is Bad Information Bad?

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rational Decision under Risk

- •Independence and Rational Decision under Risk

- •Allowing Violations of Independence

- •The Shape of Indifference Curves

- •Evidence on the Shape of Probability Weights

- •Probability Weights without Preferences for the Inferior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Risk Aversion, Risk Loving, and Loss Aversion

- •Prospect Theory

- •Prospect Theory and Indifference Curves

- •Does Prospect Theory Solve the Whole Problem?

- •Prospect Theory and Risk Aversion in Small Gambles

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •The Standard Models of Intertemporal Choice

- •Making Decisions for Our Future Self

- •Projection Bias and Addiction

- •The Role of Emotions and Visceral Factors in Choice

- •Modeling the Hot–Cold Empathy Gap

- •Hindsight Bias and the Curse of Knowledge

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •The Fully Additive Model

- •Discounting in Continuous Time

- •Why Would Discounting Be Stable?

- •Naïve Hyperbolic Discounting

- •Naïve Quasi-Hyperbolic Discounting

- •The Common Difference Effect

- •The Absolute Magnitude Effect

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Rationality and the Possibility of Committing

- •Commitment under Time Inconsistency

- •Choosing When to Do It

- •Of Sophisticates and Naïfs

- •Uncommitting

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Rationality and Altruism

- •Public Goods Provision and Altruistic Behavior

- •History and Notes

- •Thought Questions

- •Inequity Aversion

- •Holding Firms Accountable in a Competitive Marketplace

- •Fairness

- •Kindness Functions

- •Psychological Games

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Of Trust and Trustworthiness

- •Trust in the Marketplace

- •Trust and Distrust

- •Reciprocity

- •History and Notes

- •References

- •Glossary

- •Index

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

TRANSACTION UTILITY AND CONSUMER PRICING |

take on a life of its own, so that rather than simply losing some money, we lose the money and have an unpleasant meal to boot. In this chapter we discuss Richard Thaler’s notion of transaction utility and resulting behavioral anomalies. Transaction utility can be defined as the utility one receives for feeling one has received greater value in a transaction than one has given away in paying for the good. This leads to three prominent anomalies: the sunk cost fallacy, flat-rate bias, and reference-dependent preferences.

Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs

Economists are often taught about the impact of fixed costs on choice through the profit- maximization model. As we saw in Chapter 1, the firm generally faces the following problem:

max pf x − rx − C |

2 1 |

x |

|

which is solved by x*, where price times the slope of the production function is equal to the cost of inputs, p  f

f  x

x

x = r. In this case, the fixed cost C does not enter into the solution condition. Thus, whether fixed costs increase or decrease, so long as the firm chooses positive production levels, the level of production remains the same. The fixed cost does affect the amount of profit, but it does not affect the amount of inputs required to maximize profits.

x = r. In this case, the fixed cost C does not enter into the solution condition. Thus, whether fixed costs increase or decrease, so long as the firm chooses positive production levels, the level of production remains the same. The fixed cost does affect the amount of profit, but it does not affect the amount of inputs required to maximize profits.

The same need not be the case under utility maximization. Consider a rational consumer who could consume two goods, where consuming one of the goods requires that the consumer pay a fixed amount for access to a good, plus some amount for each piece consumed. This is generally referred to as a two-part tariff. One example might be a phone plan that charges a fixed amount per month, plus a fee for each text message sent. Linear pricing, or charging a fixed amount for each unit of the good, can be thought of as a special case of the two-part tariff where the fixed amount is set to zero. We will assume that the second good is priced linearly. Flat-rate pricing, where consumers are allowed to consume as much as they like for a fixed fee, can be considered a special case of the two-part tariff where the per-piece rate has been set to zero. The consumer’s problem can be written as

max U x1, x2 |

2 2 |

x1, x2 |

|

subject to the budget constraint |

|

p0x1 + p1x1 + p2x2 ≤ y, |

2 3 |

where x1 ≥ 0 is the amount of the two-part tariff good, x2 ≥ 0 is the amount of the linearly priced good, U x1, x2

x1, x2 is the consumer’s utility of consumption as a function of the amount consumed, p0 is the fixed cost of access, p1 is the per-unit price of consumption for the two-part tariff good, p2 is the per-unit cost of the linearly priced good, and y is the total available budget for consumption. Finally, x1 is an indicator of

is the consumer’s utility of consumption as a function of the amount consumed, p0 is the fixed cost of access, p1 is the per-unit price of consumption for the two-part tariff good, p2 is the per-unit cost of the linearly priced good, and y is the total available budget for consumption. Finally, x1 is an indicator of

|

|

|

|

Rational Choice with Fixed and Marginal Costs |

|

19 |

|

whether the consumer has decided to consume any of the two-part tariff good, with x1 = 1 if x1 is positive and zero otherwise. We assume for now that the consumer always gains positive utility for consuming additional amounts of good 2.

If the flat fee p0 is set equal to zero, this problem becomes the standard two-good consumption problem found in any standard microeconomics textbook. The solution in this case requires that the consumer optimize by consuming at the point of tangency between the highest utility level indifference curve that intersects at least one point of the budget constraint as presented in Chapter 1.

If both the flat fee and the linear price are positive, consumers will only purchase good 1 if doing so allows them to obtain a higher level of utility. If the first good is not purchased, then the budget constraint implies that consumers will consume as much of good 2 as they can afford, x2 = y p2, with a corresponding level of utility U

p2, with a corresponding level of utility U 0, x2

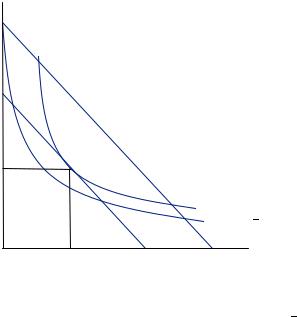

0, x2 . If the consumer purchases at least some of the two-part tariff good, the consumer decision problem functions much like the standard utility-maximization problem, where the budget constraint has been shifted in reflecting a loss in budget of p0. This problem is represented in Figure 2.1. In Figure 2.1, the consumer can choose not to consume good 1 and instead consume at x2 on the outermost budget constraint (solid line representing y = p1x1 + p2x2, or equivalently x2 =

. If the consumer purchases at least some of the two-part tariff good, the consumer decision problem functions much like the standard utility-maximization problem, where the budget constraint has been shifted in reflecting a loss in budget of p0. This problem is represented in Figure 2.1. In Figure 2.1, the consumer can choose not to consume good 1 and instead consume at x2 on the outermost budget constraint (solid line representing y = p1x1 + p2x2, or equivalently x2 =  y − p1x1

y − p1x1 p1) and obtain utility U

p1) and obtain utility U 0, x2

0, x2 , or she can find the greatest utility possible along the innermost budget constraint (dashed line representing y = p0 + p1x1 + p2x2, or equivalently x2 =

, or she can find the greatest utility possible along the innermost budget constraint (dashed line representing y = p0 + p1x1 + p2x2, or equivalently x2 =  y − p0 − p1x1

y − p0 − p1x1 p1) and obtain utility U

p1) and obtain utility U x*1 , x*2

x*1 , x*2 . If the indifference curve that passes through the point U

. If the indifference curve that passes through the point U x*1 , x*2

x*1 , x*2 intersects the x2 axis below the point x2, then the consumer is better off not purchasing any of good 1 and avoiding the fixed cost. In this case, pictured in Figure 2.1, increasing the fixed fee cannot alter consumption because the good associated with the fee is not purchased. Decreasing the fee shifts the dashed budget curve out, potentially reaching a point where it is optimal to consume both goods.

intersects the x2 axis below the point x2, then the consumer is better off not purchasing any of good 1 and avoiding the fixed cost. In this case, pictured in Figure 2.1, increasing the fixed fee cannot alter consumption because the good associated with the fee is not purchased. Decreasing the fee shifts the dashed budget curve out, potentially reaching a point where it is optimal to consume both goods.

x2 x2

x2*

x2 = (y − p0 − p1x1)/p2

x1*

U = U(0, x2)

U = U(x1*, x2*) x2 = (y − p1x1)/p2

x1

FIGURE 2.1

Utility Maximization with a Two-Part Tariff: A Corner Solution

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

TRANSACTION UTILITY AND CONSUMER PRICING |

x2 x2

|

x2* |

|

FIGURE 2.2 |

|

|

Utility Maximization |

|

|

with a Two-Part Tar- |

|

x2 = (y − p0 − p1x1)/p2 |

iff: An Internal |

|

|

|

x1* |

|

Solution |

|

|

U = U(x1*, x2*)

U = U(0, x2)

x2 = (y − p1x1)/p2 x1

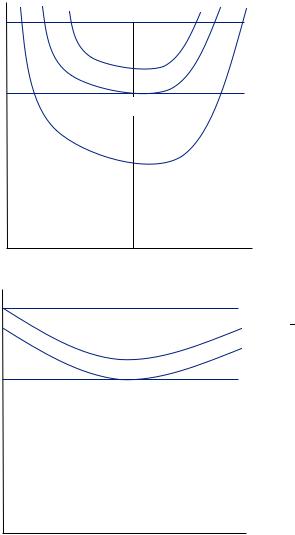

Alternatively, in Figure 2.2, the indifference curve that passes through the point U x1*, x2*

x1*, x2* does not intersect the x2 axis below the point x2, and thus a greater level of utility can be obtained by consuming both goods and paying the fixed access fee. Increasing or decreasing the fee can alter the consumption of both goods as the tangency points forming the income expansion path shift either northwest or southeast along the budget curve. However, if both goods are normal, more of each good should be purchased as the fixed fee is decreased.

does not intersect the x2 axis below the point x2, and thus a greater level of utility can be obtained by consuming both goods and paying the fixed access fee. Increasing or decreasing the fee can alter the consumption of both goods as the tangency points forming the income expansion path shift either northwest or southeast along the budget curve. However, if both goods are normal, more of each good should be purchased as the fixed fee is decreased.

Finally, if the per-unit price for good 1 is zero, as would be the case at an all-you-can- eat buffet, the budget constraint can be written as p2x2 ≤ y if good 1 is not consumed and as p2x2 ≤ y − p0 if it is. These budget constraints are illustrated in Figure 2.3. As before, if both goods are consumed, then the highest utility is obtained along the indifference curve that is tangent to the budget constraint, as in Figure 2.3. Since the budget constraint is flat, this can only occur at a bliss point for good 1. A bliss point is an amount of consumption such that consuming any more or any less will result in a lower level of utility. Given that a person can consume as much of good 1 as she would like after paying the fixed price, if there were no bliss point, the consumer would choose to consume infinite amounts, a solution that is infeasible in any real-world scenario. Consuming both goods is always the optimal solution if the indifference curve that is tangent to the lower budget constraint intersects the x2 axis above the upper budget constraint as pictured in Figure 2.3. The alternative is depicted in Figure 2.4, where the indifference curve tangent to the lower budget constrain intersects the x2 axis below the upper budget constraint. In this case, none of good 1 is consumed and consumption of good 2 is x2 = y p.

p.

In the case that both goods are consumed, increasing the fixed price has the same impact as reducing the total budget (Figure 2.3). If the two goods are complements or substitutes, then the marginal utility of consumption for good 1 will be altered by adjusting the amount of good 2 consumed. In this case, increasing the fixed price reduces the amount of good 2 consumed, which necessarily moves the bliss point for good 1

|

|

|

|

Fixed versus Sunk Costs |

|

21 |

|

x2 |

U > U(x1*, x2*) |

x2*

U = U(x1*, x2*)

x1*

x2 x2

x2 = y/p2

U < U(x1*, x2*)

x2 = (y − p0)/p2

x1

x2 = y/p2

U = U(0, x2)

U = U(x1*, x2*)

x2 = (y − p0)/p2

x1

FIGURE 2.3

Utility Maximization with Flat-Rate Pricing: An Internal Solution

FIGURE 2.4

Utility Maximization with Flat-Rate Pricing: A Corner Solution

through the change in marginal utility for good 1. Alternatively, if the two goods are neither substitutes nor complements but are independent, then increasing or decreasing consumption of good 2 should have no impact on the marginal utility for good 1. In this case, no matter what the level of the fixed price is, the amount of good 1 consumed should be the same so long as it is positive.

Fixed versus Sunk Costs

A concept that is related to, though distinct from, fixed costs is sunk costs (Figure 2.4). At the time of a decision, a fixed cost may be avoided either by not choosing the good