HISTORY OF GREAT BRITAIN

EARLY BRITAIN

Britain is both a geographical entity and a political idea. The space has been searched, excavated, and mapped with great thoroughness. Archaeology can now explain much about the earliest habitation and the evolving cultures of prehistory and the early years of the historical era. The political past is far harder to describe, because of the rarity of written evidence and other clues.

The record on the ground tells us of inhabitants who built remarkable stone monuments and equally remarkable stone dwellings. These prehistoric people are known to have been present from the end of the ice ages; they began a succession of cultures that probably spanned 10,000 years. The later cultures began to use bronze and to practice agriculture (starting around 4000 B.C.). With the Iron Age (from 700 B.C.), Britain was soon inhabited by incoming peoples loosely referred to as Celts, who originated in central and eastern Europe. These tribes had warrior-kings whose hill-forts were centers of tribal government. An agrarian people, they used iron swords and worshiped nature gods that were described by Roman observers. Substantial physical evidence of their existence can be found in all parts of Britain.

ORIGINS OF BRITAIN

The idea of Britain as a political entity is an abstraction beyond the imagination of the tribal king. It is clear that no central rule was in place either before or after the Roman occupation. The many small, pre-Roman tribal kingdoms formed shifting alliances, and some of them survived as subjects of Roman rule. The first Roman contact came with the invasion by Julius Caesar in 55–54 B.C. The occupation by the Roman legions lasted from A.D. 43 to 406. In the empire’s wake, a long turbulent period of upheaval followed, with many invasions and many realignments, again featuring tribal units that sometimes merged into larger allied groups. The one common element for Britain, Ireland, and all of Europe was the spread of Christianity. This conversion began in the later days of the empire, and it was maintained in Ireland but snuffed out by Germanic invaders of Britain (A.D. 400–600). There was no central political authority for nearly 500 years after the end of Roman occupation. The meager political record consists of a few chronicles and rare commentary, plus some later king lists that named the predecessors of medieval rulers, far into the distant and mythical past.

3

4 Great Britain

The Roman conquest was most advanced in the area roughly corresponding to modern England. Much of Wales and Scotland was controlled from garrisons but not completely subdued by the invaders. The northern frontier was marked by Hadrian’s Wall, which ran 73 miles across the narrow isthmus between the Tyne and the Solway Firth. On the western frontier, Roman garrisons in Wales and Cornwall marked limits of imperial rule. Beyond these boundaries the native Celts maintained their tribal rule and culture. Their cousins inside the Roman-occupied territory became known as “Britons”—that is, Celts whose culture had merged with the Romans. From the end of the fourth century, the imperial structure began to break down, and it was lost in the early years of the fifth century. It was then that new invasions of Angles, Saxons, and other continental peoples began. They overran much of the former Roman zone but failed to penetrate some frontier areas. Numerous Anglo-Saxon tribal kingdoms took shape in the sixth and seventh centuries. In that period they were converted to Christianity by twin missions: in the north by the Irish Celtic church (Iona in Scotland and Lindisfarne in northern England) and in the south by the Roman church, via Canterbury. The first contemporary history by the monk Bede in Northumbria was called the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (A.D. 731). In Bede’s day a set of seven kingdoms (called the “heptarchy”) ruled most of Anglo-Saxon England. They were probably the result of mergers of many smaller tribal groups. In the early eighth century, Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, Kent, Essex, Sussex, and East Anglia were the most powerful kingdoms. Kingdoms rose and fell, and the most powerful ruler was sometimes known by the name “Bretwalda,” literally a “wide-ruler” or an over-king. But still there was no unified Britain.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms became the target of Viking raids and invasions between A.D. 793 and 870. The result was the defeat of all of them except Wessex, which, led by Alfred the Great, began the process of reconquering the land that would become “England.” Alfred could only begin the process, and it took nearly a century before a form of unified rule evolved under later Saxon kings. One of the main obstacles was the large settlement of Vikings across central and northern England, known as the “Danelaw.” Edgar, king of Wessex and Northumbria, held an imperial coronation at Bath in 973, and later in the year, on the river Dee at Chester, he was rowed in a boat by eight sub-kings, including the rulers of Scotland, Strathclyde and Gwynedd. The ceremonial acknowledgment of Edgar’s lordship may have been temporary, but it was early evidence of English unification. That unity was tentative and short-lived, for by the end of the century there were more Scandinavian invasions, leading to Cnut of Denmark’s conquest and rule of a united England. The period of Danish rule lasted from 1016 to 1042, followed by restoration of the Anglo-Saxon king Edward (the Confessor, ruled 1043–66).

NORMANS AND ANGEVINS

After Edward’s death and the very brief rule of King Harold, there were two powerful invasions in 1066: the Norwegians in the north and the Normans in

Early Britain 5

the south. Although Harold defeated the king of Norway, the Norman invasion succeeded. William the Conqueror (1066–87) wiped out most of the AngloSaxon nobility and introduced a new aristocracy. The conquest linked feudal lordship to strong existing royal institutions, so the Normans were able to create a powerful and centralized English (or Anglo-Norman) kingdom. But the first half-century of Norman rule also produced a cross-channel empire with divided objectives. The English unit was strong and centralized, and it was fortified against its Welsh and Scottish neighbors. There was hereafter no ready way to assimilate all of Britain; the English would dominate them for nine centuries, but assimilation and a unified culture and society lay a long way ahead.

Scotland had an even cloudier early history, with little documentation before the 12th century. The prehistoric people called “Picts” were contemporary with the Romans, and they were joined in the sixth and seventh centuries by Irish invaders (called “scotti”—whence the name Scotland). Also, parts of Scotland were inhabited by Britons (Strathclyde) and by incoming Angles (Lothian) and Vikings. The mission of the Irish (Celtic) church greatly assisted unification around 850. Scottish kings followed the custom of tanistry, or inheritance by near male relatives. This provided ample opportunity for royal bloodshed. King Malcolm (1005–34) killed a number of tanists, and his grandson Duncan succeeded him, only to be murdered by Macbeth (1040). He in turn was slain by Malcolm III (1058), the king who faced the new Anglo-Norman regime in England. He successfully resisted the Norman advance in the 1060s, although the next two centuries saw considerable movement of Anglo-Normans into the south of Scotland.

Wales was made up of a collection of small tribal groups. Here Britons (Celts) spoke one form of Celtic language and had much in common with kin in Cornwall and Brittany, with whom they shared cultures and engaged in trade. Wales itself was hilly, remote, and poor. It was isolated by the Norman conquest when William I created frontier earldoms (Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford), which were granted extensive powers and made responsible for defense of the border. This arrangement assured both subordination and separation for Wales.

Monmouth was on the southern Anglo-Welsh border, an area that was the home of a churchman named Geoffrey. In 1136 Geoffrey wrote the most compelling story about Britain in all of the middle ages, The History of the Kings of Britain (Historia Regum Britanniae). He lived and taught for much of his life in Oxford (before there was a university there), and he was a singular champion of the Britons. A mixture of myth, romance, and history, his book was one of the most popular works in the Middle Ages, with nearly 200 copies of the manuscript still in existence. Geoffrey claimed that he translated the story from an old book written in Welsh (which has never been found). He told of Brutus, a descendant of Aeneas of Troy, who came to Britain around 1200 B.C. From him a line of kings was traced down to the last British ruler, Cadwallader, who was defeated by the Saxons in the seventh century. One of the high points in Geoffrey’s narrative was the story of Arthur, king of the Britons and heroic leader of the ancestors of the Welsh, whose return to power was prophesied by the seer Merlin. The real significance of Arthur’s story did not lie in British polit-

6 Great Britain

ical history, however. This mythic figure, of prophetic birth and prodigious valor, was a cultural stereotype for the age of chivalry. He was thus adopted by continental writers and went on to a long literary life over the next five or six centuries. But as a British political figure, Arthur represented a ruler who could legitimize native aspirations in the void that was British political history. The real world of the 12th century saw very different tendencies.

Just as Geoffrey of Monmouth died, the throne of England was reclaimed by Henry of Anjou in 1154. The grandson of Henry I and great-grandson of William the Conqueror assumed the throne that had been bequeathed to his mother and contested by another prince. When Henry II restored his family’s rule, he also brought back the cross-channel empire and the French orientation of William the Conqueror. This again made British interests secondary to continental ones, a condition that would endure until the 15th century. Henry had earlier married Eleanor of Aquitaine and thus enlarged the royal domain. But she and the four sons she bore him caused endless political turmoil.

England in the 1150s was a source of wealth, and its tax revenues probably were its most appealing feature to continental rulers. This wealth might be directly exploited through the exactions of feudal overlords, but from the 12th century the process of exploiting that wealth became entangled with critical legal developments: the birth and growth of a common law dispensed by royal judges; the tradition of petitioning the Crown, which issued charters of liberties; and the summoning of councils to approve taxes and other measures, which eventually produced the institution of parliament.

The king’s authority was supported by the church, but he was subject to church authority. In the 12th century there was a major clash between the authority of the pope and that of the Holy Roman Emperor, a dispute that echoed through all royal courts. The issue was whether the pope or the secular rulers controlled the appointment of bishops—a source of continuing tension in the Middle Ages. There were many other points of friction between clerical and lay leaders. Henry II had a dispute with his archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, which ended in a particularly grisly episode. Four of the king’s knights murdered Becket, and while the king denied giving the order, he did public penance for the crime. In the wake of this event, Henry made his famous expedition to Ireland (1171), mainly to discipline his vassal, the earl of Clare, who seemed to be assuming too much power there. But Henry also carried a papal bull vesting him with the power of lordship in Ireland.

Henry’s son Richard I (1189–99), known as the Lion Heart, succeeded to the throne of England, but he spent five years on crusade (and in captivity) and five more in wars on the continent. His youngest brother John succeeded him (1199–1216). Due to the loss of Normandy in 1204, John spent more time in England, but his harsh rule brought resistance and, in turn, the issue of charters to the church, to the city of London, and eventually to his barons in 1215. A large proportion of that document, the “Great Charter” (Magna Carta) was reissued some years later under John’s son Henry III.

Henry III managed his inherited territories with indifferent success. He faced a strong French king, Philip II, and he encountered resistance in Wales, Scotland,

Early Britain 7

and Ireland. In all his dealings, Henry was less warlike than his ancestors, but this did not make his subjects less rebellious. During Henry’s reign there were periodic meetings of barons and clergy, sometimes augmented by the attendance of commoners (knights and burgesses). These were the earliest examples of the institution of Parliament. When a serious revolt occurred in 1265, a so-called model Parliament was summoned. This unusually representative body was dismissed by the king’s son, Prince Edward, who became a much more strong-willed ruler than his father. Edward I (1272–1307) wanted tighter control of his domin-

King John of England submits to the Barons at Runnymede and agrees to sign the Great Charter of

British Liberties, the Magna Carta, 1215.

(Hulton/Archive)

8 Great Britain

ions and began with a campaign to improve the government of Gascony. Wales was soon brought to heel, and a statute was enacted to annex its government (1284). Edward also enacted a series of major statutes to increase his power over the feudal nobility, and when the Scottish line of succession ran out, he intervened to assure a pliable ruler in 1290. But Edward met his match in Scotland: a prolonged series of campaigns added to the demands for revenues already inflated by castle-building in Wales and costly ventures in France. Victory eluded Edward, as William Wallace led a popular campaign against the English (1297), and Robert Bruce energized a revived claim to the throne (1306).

Bruce’s efforts were capped by a victory at Bannockburn in 1314, and in 1320 the Scottish clergy produced a declaration of independence (Arbroath). These events occurred during the troubled reign of Edward II (1307–27), one of the least martial of English rulers. His ineffective government and his personal character were fuel to hostile nobles, who led an unsuccessful palace revolt in 1310. The contrast between Edward II and his son could hardly have been greater. Edward III (1327–77) was placed on the throne after his father was deposed and murdered by his mother and her lover. Soon Edward III took power in his own right, and about 1340 he launched the English campaigns that began the Hundred Years’ War with France. This conflict had roots in a failed French succession, but it had more to do with trade and dynastic power. During the 14th century it was no accident that the focus on France was accompanied by a serious loss in English authority in Ireland, fitful intrusions in affairs of Scotland, and growth of rebellious sentiments in Wales.

FOURTEENTH-CENTURY CRISES

The convergence of a number of crises in the second half of the 14th century marks the period as one of unusual significance. As the English continued to fight in France, the awesome toll of the “Black Death”—the bubonic plague, which struck in 1348—was not only terrifying in itself, but it led to a host of major social changes. The deadly disease would kill somewhere between 10 and 50 percent of the population in communities small and large. Modern attempts to assess the toll are hindered by lack of population data in the Middle Ages, at which time there was limited interest in statistical information. Estimates of the general population before the plague range from 4 million to 6 million; for the end of the century, between 2.5 million and 3 million. There is no way to calculate the precise impact, but there are many chilling accounts from specific communities, monastic houses, and towns or neighborhoods. There is no question that the mortality rate was severe. Moreover, the plague was not a single event: it returned in 1361, 1369, 1375, 1390, and 1405. Recurrence made it even more frightening and reinforced major impacts: a shrinking work force, declining land values, and falling production. There were desperate acts to offset these effects; for example, the Statute of Labourers was enacted to freeze wage levels (1351). The plague unleashed powerful forces of social and economic change, forces which no government, certainly none in the Middle Ages, would be able to control.

Early Britain 9

The consolation of religious faith was never more essential than in the plague years, and yet the church was subject to unprecedented stresses at the same time. Due to the warfare between England and France, there were extraordinary pressures on the Catholic Church. One manifestation of this was a debate over the powers of the papacy to appoint clergy for positions in the English Church during the 1350s. The roots of this resistance went back to the period when the popes moved to Avignon, a papal enclave in southern France (1305–78). Parliament passed laws banning papal appointments and restricting appeals to the Roman curia. This tension appeared again when a schism split the church in 1378.

In this era of war and unrest, there was significant theological controversy. The central figure was John Wycliffe, an Oxford teacher and diplomat. Wycliffe (ca. 1329–84) was one of the foremost critics of church government and papal power. An early advocate of translation of the scriptures into English, he eventually disputed central doctrines of the church (e.g., “transubstantiation,” the belief that the bread and wine of the eucharist become the body and blood of Christ in the course of the sacrament). Wycliffe was condemned by the church but, protected by the university and by his patron, John of Gaunt, he was able to live out his life in peace. However, his followers, known as Lollards, persisted in some of these views and were to suffer later on.

While Wycliffe was on trial in the 1370s, the government faced its own problems in France. Needing new resources, Parliament adopted “poll” taxes in 1377, 1379, and 1380. The last of these triggered the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. A large body of rebels marched on London from Essex and Kent. Their leaders included a renegade priest named John Ball, who called for the removal of all bishops and archbishops. They entered the city, destroyed a number of buildings, and killed the king’s chancellor and treasurer. But the rebels were outnumbered by government supporters. When the 14-year-old King Richard II (1377–99) rode out to meet them at Smithfield, the rebel leader Wat Tyler presented a list of demands. However, during a scuffle Tyler was killed by the lord mayor of London. Soon all the rebels dispersed, and the unrest in a number of counties was followed by arrests and harsh punishments. Yet it may not be just a coincidence that the next generation saw the ending of villein status (unfree tenants who were bound to a lord’s estate). And there could never be quite the same social order after events such as these, especially as there were severe strains at the upper end of society.

The reign of Richard II witnessed a breakdown of relations between the crown and the nobility, and the stresses magnified commonplace feuds into constitutional clashes. Of course, these were not without precedent: barons had opposed King John (1215), they had resisted Henry III (1258 and 1265), and they tried to impose restraints on the royal power of Edward II (1310). The reign of Edward III had a long spell of amity thanks both to his victories and to his support of chivalric ideals (e.g., the Order of the Garter). But the king’s later years saw this harmony evaporate. Defeats in France and distrust of Edward’s advisers brought about the so-called Good Parliament in 1376. The Commons brought charges of court corruption and military incompetence, and

10 Great Britain

the process of impeachment (against two of the king’s ministers) was used for the first time.

When Richard II took the throne the next year (1377) there was some relaxation. But the tensions revived after the Peasants’ Revolt. Richard made this worse by his choice of advisers and his reckless tactics against those who opposed him. Upon coming of age, he encountered more opposition. In 1386 Parliament impeached his chancellor, Michael de la Pole. In 1387 his advisers were charged with treason by a faction known as the “Lords Appellant.” In 1388 the “Merciless Parliament” executed some of the king’s supporters. Richard reasserted his power in 1389, arresting some opponents and exiling others. The king also confiscated some estates, including those of Henry Bolingbroke, the heir of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster. Richard unwisely made expeditions to Ireland during this tense period, and on the second of these, in 1399, Bolingbroke led a small invading force, which defeated and captured the king. This coup removed Richard and inaugurated the Lancastrian dynasty under Henry IV (1399–1413). The events of 1399 did not restore stability. Indeed, the years after 1350 saw multiple crises in government, religion, and society—a pattern that would continue for much of the 15th century.

THE END OF

THE MIDDLE AGES

1399–1509

The condition of the English monarchy in the 15th century was chaotic: five depositions, a devastating defeat in France, and a generation of civil warfare. Until recently, historians allowed this chaos to represent the entire period and the general character of the century, which was then rescued by the appearance of the Tudors and a “new monarchy” in 1485. Now it seems evident that this picture was one that served the interests of contemporary and later authors, exaggerating the misery before and the recovery after 1485. The central point is that the government system was not defective: weak kings and ambitious nobles robbed it of the essential bonds it needed to function.

A second major correction recognizes that the rest of British history was not dependent upon or represented by the crisis in government. There were in fact multiple developments—in religious, intellectual, social, and economic life— which together were creating a different Britain from that of the medieval period. England, with its weak crown and its strategic vulnerability, commanded little respect in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. But England’s wealth and its central position, sometimes challenged, would be the basis of British unification in the 16th century.

WAR AND LORDSHIP

It is helpful to relate the events of this century to the evolving ideas of lordship, the crux of politics. Already in the 14th century the classic feudal ties were replaced by “bastard feudalism,” or contracts of service on cash terms. The 15th century saw this process extended, and the evolution of private armies, or “liveries” in the pay of a wealthy nobleman, became a regular feature. There was not as yet a national army, for as yet there were only fledgling ideas of nationality. The “nations” of this century were unsettled. Were the English a nation or a group of regions? Were the Welsh, Scots, and Irish coherent national groups? Were the French the same as the Burgundians, Bretons, and Gascons? It was still easier to find one’s identity with a lord, whether a king or aristocrat. Further, it should be remembered that in the 15th century the kings and great men could gather forces of several thousand under their banner, and this

11

12 Great Britain

number would be considered quite substantial. The armies that would invade France under Henry V (1413–22) were 5,000–6,000 strong; the armies fighting in Wales under Henry IV (1399–1413) were almost as large on some occasions. The forces in battle during the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485) were usually small, and the 10,000 of both sides at Towton (1461) far exceeded all the other battles. Thus any rebel group, with skill and luck, might pose a serious threat.

In summer 1399 Henry Bolingbroke invaded England with a tiny force of 300 men. He had come to reclaim his Lancaster inheritance, which King Richard II had taken from him. The king hastily returned from his campaign in Ireland but was captured by Bolingbroke, whose allies included the Percys of Northumberland. By August Bolingbroke had claimed the crown as Henry IV, by descent from Edward III through his third son, John of Gaunt. His claim was fortified by the fact that Richard had no heirs, but Henry’s coup spawned a whole series of rebellions: a plot to kill him by Richard’s supporters, leading to the former king’s murder; a revolt in Wales led by Owen Glendower; a revolt by the Percys in 1403; and a related challenge from the archbishop of York, who was executed in 1405.

The Welsh rebellion was not a simple reaction to Richard’s deposition, although Henry might be forgiven for seeing the hand of his rival’s followers in it. The revolt was an attack on English colonial power by native Welsh rebels. Glendower attacked English castles and town settlements; he made alliances with Northumberland and with the Scots and the French; and he eluded capture by the king’s forces, even though they invaded Wales several times. But Glendower’s plan for an independent Wales was crushed. Henry was able to dispose of most of the threats to his rule, and when he died he left four sons to succeed him. There was only one competing claim to the throne, and the earl of March chose not to advance it, though it would later be adopted by Richard of York in the 1450s.

Henry V succeeded his father in 1413. His hold on power was quite secure, threatened only by two inept revolts in 1415. Sir John Oldcastle, a Lollard and a military servant of the king, was convicted of heresy, and he and his supporters were crushed. The earl of Cambridge tried to exploit the March claim to the throne, but the earl of March exposed him, and he was executed with his fellow plotters. But Henry V was intent on plans for French conquest by this time. He prepared an army of 10,000, made an alliance with Burgundy, and set sail in August 1415. After a long siege at Harfleur, Henry marched across country and engaged a much larger French force at Agincourt, winning a stunning victory. He followed this in the next few years with further victories in Normandy, and by the Treaty of Troyes (1420) he became regent of France and heir to the throne, taking the princess Catherine as his bride. But Henry died just before the French king in 1422, leaving a nine-month-old heir, Henry VI. The boy would be crowned both in France and in England, but he would also preside over the final expulsion of the English from France.

Henry VI did not rule in his own right until 1437. In the interim his uncles— John, duke of Bedford, and Humphrey, duke of Gloucester—and his greatuncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort, vied for authority. At the same time there was

The End of the Middle Ages 13

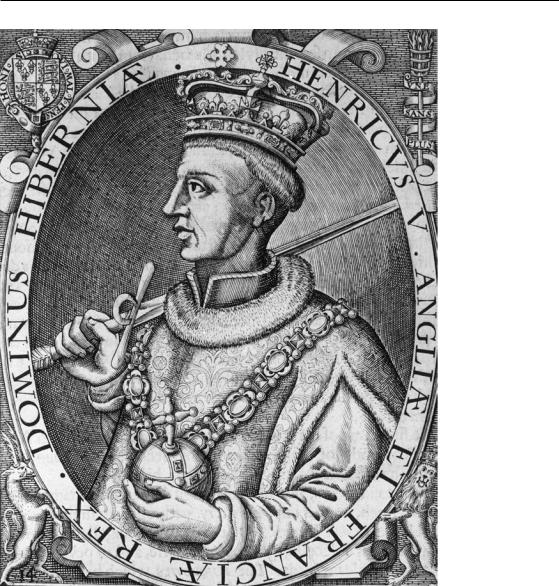

King Henry V

(Hulton/Archive)

growing resistance in France, led by Joan of Arc and by resurgent factions. The coronation of Charles VII, the death of the duke of Bedford, and the loss of the alliance with Burgundy made it essential to make peace. Henry married the princess Margaret of Anjou as a conciliatory gesture in 1445, but French resistance continued, sweeping the English out of Normandy in 1450 and Gascony in 1453. The great continental adventure was over, with only the colony at Calais remaining in English control.

14 Great Britain

The failure in France tended to mask early success at home. The English succession was untroubled by revolt, as the royal council imposed its control firmly. The house of Lancaster seemed to have brought a new stability to English politics, but in a short time the royal uncles and other leaders fell out over the events in France and the constitutional vacuum in England. Henry had his first coronation in London in 1429. He was then taken to France, but the planned coronation there was delayed and then had to be conducted quickly so that he could return to safety in England (1432). There was now a joint royal council for the two kingdoms, but this did little to reduce the conflicts between the senior advisers. Even when Bedford died in 1435, there was no cessation of friction. Henry VI began to assume power in his own right in 1437, sharing authority with the royal council. The timing was not in his favor: heavy expenses had been demanded from parliaments since 1415 and before, and the tide of victory in France was being reversed. The cost and trouble of a French crown was now clear to see. And in the next few years his subjects would see that Henry VI was not a king like his father.

Even a skillful ruler would have struggled with the conditions facing the young king. But he was inexperienced, extravagant, and lacking in good judgment. His courtiers assumed more and more control of the royal council, and in so doing they aroused increasing hostility. One of the king’s leading advisers, the duke of Suffolk, was murdered in 1450. In the same year there was a serious popular revolt known as “Cade’s Rebellion.” Even more serious, at the time when the French inflicted the defeat in Gascony in 1453, Henry suffered a mental collapse, and Richard of York asserted himself as regent. He carried on the claim to succession of the earl of March, which had been bypassed in 1399. Although Queen Margaret presented Henry with a son in 1453, there was conflict over the succession, and the fighting which soon began would later be dubbed the Wars of the Roses after the symbols of the Houses of York (white rose) and Lancaster (red rose). After several battles, Richard claimed the throne in 1460, but he died soon after in a battle at Wakefield. His son assumed the title, supported by the earl of Warwick (“the kingmaker”), and as Edward IV defeated the army of Queen Margaret and Henry VI at Towton in March 1461, affirming his title as king.

NEW MONARCHS

Edward’s reign can be divided into a troubled first half and a much more successful second. At first he was confronted with the forces of King Henry (captured in 1465) and Queen Margaret (in exile in Scotland). He also could not rally all the nobility to his side; indeed, by 1469 he had alienated his most powerful backer, the earl of Warwick. Thus in 1470 there was a coup: Warwick forced Edward out and restored Henry VI. This lasted but a short time. In March 1471 Edward returned and defeated Warwick (Battle of Barnet) and Margaret (Battle of Tewkesbury). Her son Edward was killed in the battle, and Henry VI died in the Tower of London, probably murdered. The major phase of the Wars of the Roses had ended with a decisive Yorkist victory. Edward IV had secured his

The End of the Middle Ages 15

throne, and his rule for the next 12 years proved successful. He placed his broth- ers—George, duke of Clarence, and Richard, duke of Gloucester—alongside a set of loyal noblemen, in charge of the several regions of the kingdom. Edward resumed the English royal quest for a French title, but his allies deserted him during his expedition in 1475, and the king settled for a ransom and trade and marriage settlements from the king of France. At home Edward’s policies included financial reforms, support for merchants, and significant reduction in the level of taxation. But this reign was also troubled by noble factions: the king’s brother George, duke of Clarence, was involved in treacherous acts, and the king had him attainted by Parliament and executed in 1478. The treachery of his other brother would dominate affairs after Edward’s death in 1483.

The king’s son would have become Edward V, but his accession was prevented by his uncle Richard, duke of Gloucester. The 12-year-old prince was declared illegitimate, and Richard assumed the throne as Richard III. The prince and his younger brother were never seen again, apparently murdered in the Tower on their uncle’s orders. Richard had ruthlessly silenced most of the leaders of the court who opposed him, and his acts reopened the gates of dynastic warfare. His short reign was preoccupied with numerous efforts to buttress his claim to the throne. But there was a rival in exile, who soon would challenge him.

Henry Tudor was the son of Edmund Tudor and Margaret Beaufort, descended from the ubiquitous John of Gaunt. As earl of Richmond, he was a minor Lancastrian supporter who went into exile after Tewkesbury. Henry received enough support from France to mount an expedition in 1485. He landed in Pembroke and marched through Wales and western England, rallying support. Richard’s army marched to meet them, and they fought at Bosworth in Leicestershire. The king’s army was larger than Henry’s, but it was not as loyal. When Richard was killed, his forces dissolved. Henry marched to London and claimed the throne as Henry VII.

The new dynasty, a partial restoration of the Lancaster line, was deliberately joined to that of York by Henry’s marriage to Elizabeth (daughter of Edward IV). But the chaos of factional warfare was not quickly nor easily ended. Henry’s own claim was tenuous; his wife’s legitimacy had been denied; there were rumors that the young princes were still alive; and of course no one expected a sudden end to the bitter and bloody disputes, deceptions, and treachery of the last generation. Indeed, the first half of Henry’s reign was consumed by the fallout from this atmosphere. There was a Yorkist rebellion in the name of Edward, earl of Warwick (son of the late duke of Clarence and nephew of Edward IV). Led by an imposter named Lambert Simnel, posing as the earl, this group was defeated at the Battle of Stoke in 1487. Another imposter named Perkin Warbeck posed as Richard, duke of York. The king beat his forces in 1497, and Warbeck was later executed along with the real earl of Warwick in 1499. It is perhaps significant that Henry had the apparently easy task of crushing fraudulent enemies, but the main point was that the Crown was not yet secure.

The reign of Henry VII was for a long time regarded as a “new monarchy.” The new king’s effectiveness, against the background of previous instability, goes far to explain this impression. But Henry only made better use of existing

16 Great Britain

royal powers. What was new was the reduced size of the English nobility and the exhaustion after 30 years of aristocratic factional fighting. The king restored order and discipline, was attentive to royal finance, exploited diplomatic opportunities to improve trade and secure his own position, and generally brought an efficient and determined approach to royal government. The outcome was strict monitoring of aristocratic factions and stronger royal justice, with a consequent decline in rebellion. Henry achieved this by use of a strong royal council, with enhanced judicial powers in its meetings in the court of Star Chamber. He exploited regular assets like feudal dues, crown lands, and forfeitures, plus occasional heavy levels of parliamentary taxation. But Henry husbanded these resources, and with a pacific foreign policy and steady support of trade, he accumulated an unheard-of surplus in the royal treasury in the course of his reign.

Little has been said here of Parliament. It once was thought that the early Lancastrian parliaments had begun a precocious democratic development, claiming to control purse strings and public debate. But it appears that the crisis conditions surrounding so many meetings, the need to raise ample revenues for French campaigns, and the recurrent use of parliamentary councils to ratify royal power and title lent an appearance of power to these councils that was misleading. Henry Tudor convened Parliament frequently in the first half of his reign, but as his power solidified and his finances stabilized, he only had to summon Parliament twice in the second half.

Finally, Henry performed the most essential of royal duties by providing legitimate heirs: his sons Arthur (1486) and Henry (1491) and daughters Margaret (1489) and Mary (1496). Arthur was wed to Catherine of Aragon in 1501 but died six months later. She would later marry the younger son, Henry, in 1509. Margaret was married to James IV of Scotland, a union that eventually united the two crowns in 1603. The Tudor dynasty brought an end to the debilitating series of conflicts that had plagued England and Britain during the 15th century. How had the rest of society fared in this same period?

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGES

English religious life at the end of the Middle Ages is hard to see clearly because of the glare of the 16th century’s reformation. The Church of the 15th century was deeply involved with papal appointments, judgments, and finance. It also included large orders of monks and friars—in Britain, some 900 religious houses in all. To the later Protestant, these were potential sources of corruption and abuse, but to contemporaries they were quite normal. From the archbishops and bishops and other senior clerics, many of whom held important positions in royal government, to the parish priests—rectors, vicars, curates—churchmen were a competent and comprehensive administrative corps. They attended to the souls of their flock, but they also managed estates, collected tithes, and conducted courts at all levels. The 40,000–50,000 clergy in the British Isles were for the most part dutiful and conscientious. But recent relations between Rome and the national churches had injected a dangerous division. After the “captivity” of the papacy in Avignon (1308–78) there was a schism for the next 40

The End of the Middle Ages 17

years, during which there were two and sometimes three rival popes. Such a crisis opened the door to criticism, already manifest in such measures as the statutes passed in England to prevent papal appointments and to limit its legal jurisdiction (Statute of Provisors [1351] and Statute of Praemunire [1392]). Out of this situation there came mounting anticlerical criticism and rising reform ideas. When movements for reform began, attention was always drawn to the most vulnerable individuals and practices. The Lollards in the early years of the 15th century were numerous enough to provoke major reaction; statutes and orders to root them out had had some effect by the second decade. But another reaction, just as important in the overall picture, was the growth of individual expressions of faith. There was considerable interest in devotional literature and lay piety in the 15th century—for example, the writing of Richard Rolle, a Yorkshire hermit, and Margery Kempe, wife of a burgess of Lynn; or the devotional work of Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII. Much of the writing was in the vernacular, and lay involvement in the church was greatly encouraged.

The 15th-century economy experienced some changes that would have created problems even without the extraordinary burdens of warfare, foreign and civil. A declining population meant contraction in agriculture; a shrinking money supply and falling prices were common features; and trade disruptions and harvest failures were compounding problems, especially in the middle of the century. The most significant developments included a shift to pastoral farming and the transfer from export of wool to manufacture and trade in woolen cloth. The phenomenon of failed villages, difficult to trace but evident in many comments and complaints, reflected the combined effects of population decline, falling wool exports, and conversion of farmland to pasture. Part of the picture had to be the improved ability of peasants and workers to move from one place to another: a fairly high demand for labor gave the worker unprecedented mobility.

Towns and trade showed important signs of growth in the 15th century. London grew more rapidly than other towns, consequently increasing its share of trade and economic activity. There and in other urban centers, the life of the community was controlled by the powerful guilds, which provided the mayors and aldermen and other leaders. Many of the most successful among them bought estates and entered the gentry. Cities like York, Bristol and Norwich were also thriving by the end of the century. The towns that suffered most had been dependent on the trade in raw wool. Their trade had been burdened by high duties during the war years of the 14th and 15th centuries, which added costs to the continental manufacturers, a de facto tariff behind which English cloth manufacturing was able to develop. This was aided by the availability of water power for mills as well as other natural advantages. Several regions of England (the Cotswolds, Yorkshire, and East Anglia) produced special products which became highly competitive. As the trade expanded, London’s share grew, and merchants there became more involved in the growth of English shipping. Where much of English trade had been carried in Florentine and Venetian vessels, the second half of the 15th century saw English shipping ventures into the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, the precursors of 16thand 17th-century mercantile growth.

18 Great Britain

Society saw several very important changes. The laws of supply and demand favored the peasantry and brought reciprocal shifts in standards of living; landlords lost ground while tenants and workers improved. The decline of villeinage had begun in the previous century, and it was completed in the 15th. This was marked by the increase in copyhold tenure; that is, the granting of a copy of the manor court roll to a tenant, which amounted to a permanent lease. This much more favorable tenancy was a direct consequence of the relative advantage tenants possessed due to population decline (the Black Death). That condition began to be reversed by the end of the century.

There were some steps toward defining the class that became known as the “gentry.” The higher nobility, the peerage, had been defined more fully in the 14th century. They were the elite of the landowning class; the lesser but still wealthy landowners were consigned to the ranks of knights, esquires, and gentlemen. These were indeterminate groups whose ranks were swelled by increasing fortunes and new purchases of landed estates. In the 1440s those with incomes of £40 or more were enjoined to take a knighthood, though many did not. That status was required for one to be elected as a knight of the shire to attend Parliament (1445). There were no such clear delineations pertaining to the esquire and the gentleman. The terms placed their bearers in the wide zone between nobility and yeomanry, or small farmers. These were the more affluent local men, who were expected to serve in Parliament or as justices of the peace or as grand jurors—in other words, the governing class.

The 15th century also saw significant intellectual development and, apparently, increasing literacy. Sir Thomas More made the implausible claim that by 1500 half of the English population was literate. Assuming that he was correct in seeing significant improvement, some credit must be given to the popular devotional literature of the time and to the growing number of schools and colleges founded in the second half of the century. Moreover, the appearance of the printing press by 1476 aided the circulation of reading material. The century had a significant rise in the number of laymen who held official posts, many of which were formerly occupied by churchmen. There was also the oft-noted but elevated category of the intellectual elite, many of them exposed to and influenced by the humanist scholarship of both Italian and northern European origin. The number who traveled to these regions, returning to teach and write, was increasing. At another level, the study of law was being expanded in the Inns of Court, the schools for English lawyers. While it was too soon to speak of an English “renaissance,” the 15th century was providing some essential foundations.

England’s political troubles might have enabled her neighbors to resist her control. But there was intermittent exercise of that control, and there was no concerted effort to destroy the foundations of English power, with the exception of the Glendower revolt in the early years of the century. That exception to the rule also indicated the difficulty of resistance. While the revolt was of great duration (1400–15), its accomplishment was negligible. When the English captured James I of Scotland, an ally of France, and held him for ransom (1406–24), that seemed to show the weakness of the northern kingdom, but

The End of the Middle Ages 19

there was never a genuine threat to the Scottish monarchy. Perhaps only the increasing autonomy of Irish and Anglo-Irish leaders was cause for real concern. Yet England experienced no apparent fundamental weakening in relation to her immediate neighbors, and a restoration of English royal authority began to counteract the chaos of the 15th century. Sir John Fortescue, a constitutional lawyer of the time, had recommended a government less dependent upon public finance and less subject to the interests of powerful aristocrats; Edward IV and Henry VII began to achieve this. By the 16th century the power of the English monarchy had been stabilized. In the testing crises of the new century, a more centralized British state would be formed.