A NEW SOCIETY

1707–1850

The Stuart dynasty was supplanted by the House of Hanover when Queen Anne died in 1714. Over the next half-century Britain became the strongest military power in Europe, built a global empire, and refined the constitutional monarchy inherited from 1689. The government was dominated by an entrenched Whig oligarchy until 1757, owing in part to the threat of a Jacobite restoration, which was identified with Tory supporters. This threat was defeated on two major occasions, in 1715 and 1745, and then subsided. The main concern then became the status of the American colonies, whose rebellion in 1776–81 threw off British rule. This coincided with a period of political instability in England, ending when the French Revolution of 1789 brought major European war (1793–1801, 1803–15). A victorious coalition led by Britain defeated Napoleon Bonaparte, but the postwar years, while peaceful, were a time of tremendous social stress and political tension, all of which helped to induce a remarkable series of reforms from 1820 to 1850.

The new society that emerged in this period enabled the middle classes to gain in numbers and affluence by 1800, and over the next half-century that momentum carried the poor toward a social recognition hitherto unknown. In 1850 British society still had old familiar outlines, but its structure was coming to resemble that of today. There was also a new appreciation of social class and social justice. For over a century Britons had absorbed the fruits of a new consumer culture fed by a global empire, and this broad wave of development was destined to remake society.

In the 17th century the old society had featured a tiny elite ruling in a patriarchal order with a focus on the land and a dominant religion, and with the lower orders settled in seemingly permanent subservience. This order of things was now and then marred by famine, plagues, and pestilence. More significantly, in the middle of the century an apocalyptic revolution had overturned the old structure. The attempt to restore the old order after 1660 could not succeed, as many new elements—and some old frictions—were present.

What was distinctive and valuable in the changes that occurred was the flexible stability that the older British society, and its newer forms, retained throughout the period. Numerous observers commented on the differences between

45

46 Great Britain

most of Britain and her continental neighbors: mobility among classes, commercial opportunities, and broad access to law were paramount. This flexible stability enabled Britain to move through the changes that this chapter will trace, without the trauma of revolution. And when pressure for political reform grew in the 19th century, the memories of two revolutions—the bad in 1649 and the good in 1689—also promoted moderation. One of the most pervasive factors associated with the changing climate of the latter half of the 17th century was a broad stream of intellectual development that reconfigured the natural world and in so doing challenged elementary ideas of society.

THE ENLIGHTENMENT

The term “enlightenment” has had an odd history. It was first a self-conscious description of contemporaries who saw themselves escaping the “darkness” of the world of medieval thought, dominated by religion and religious controversy, heedless of man’s mental capacity, and dogmatic in its treatment of new ideas. They found their escape route by way of empirical study and logical deduction. Historians looking for the roots of the French Revolution of 1789 found a brilliant corps of writers (the philosophes) in 18th-century France (Montesquieu, Diderot, Voltaire) who seemed to be the inspiration for later events. They were joined by an amazing band of intellectuals in 18th-century Scotland (Hume, Hutcheson, Kames, Smith) whose work received recognition as the “Scottish Enlightenment.” But there had also been nearly a century of philosophic thought in England (Bacon, Boyle, Newton, Locke) that formed part of the basis for the Age of Enlightenment, as it was called. Whether or not these thinkers should be credited with triggering Europe’s enlightenment, their contributions to Britain’s social and political history must be considered.

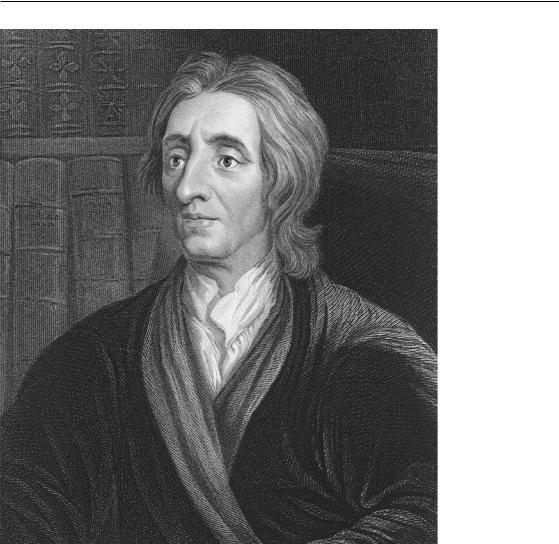

The notable thinkers and early scientists in 17th-century Britain rebuilt the understanding of the cosmos, the natural world, and the human function within it. Francis Bacon was the most influential early figure, noted for his works on inductive method. William Harvey was a physician who described the circulatory system of the human body, Roger Boyle experimented with gases and their properties, and Sir Isaac Newton developed a theory of gravity to explain the operation of the universe. After the Restoration (1660), the Royal Society was incorporated to foster the work of such men. Their significance was to open a new avenue for human intelligence, outside the bounds of traditional, theological explanation. At the time of the Glorious Revolution (1688), the greatest thinker of his age, John Locke, recast the understanding of government, evaluated the role of the church, and speculated on the nature of human psychology in his books Treatises on Government (1689) and Essays Concerning Human Understanding (1690).

This same period saw passage of a Toleration Act (1689), which allowed (and regulated) the practice of Protestant dissent. It was not generous (Catholics and Quakers were excluded) and it was intended more to fortify the Anglican establishment than to honor the beliefs of others. Nevertheless, the next generation became an important time for the growth of dissent (Presbyterians, Baptists,

A New Society 47

John Locke

(Hulton/Archive)

Congregationalists), as well as a time of emerging public expression of deism, that is, the belief in a god whose existence was proven by nature, not revealed truth. This was confined to a very small segment, and orthodox churchmen regarded with it horror. Nevertheless, it was another sign of the Enlightenment’s influence, which would continue to stimulate religious diversity and debate.

In a more pragmatic way, the end of the century saw the flourishing of political and social economics. A powerful dose of empiricism was added to the operation of government: systematic calculation in finance and the development of banking and exchange facilities were important advances. They were, of course, subject to manipulation, as in the infamous South Sea Bubble scheme, which

48 Great Britain

caused widespread ruin when it collapsed in 1720. But on balance the new type of finance was the key to Britain’s commercial growth in that era. In the wider society there was an effort to count the population. The economist Sir William Petty pioneered in this, beginning in mid-century Ireland. In 1688 the statistician Gregory King calculated the size of the various levels of English society, using hearth tax returns as a basis for computation. Only slowly did society accept the idea of precise statistics: the Ordnance Survey mapped the country from 1791, and the decennial census began in 1801.

Another form of the Enlightenment can be seen with the expiration of the Licensing Act (1695), when toleration for all manner of publications began to increase. Newspapers, journals, and other printed works multiplied, and clubs and associations for the sharing of information and ideas grew rapidly. While both of these were primarily urban phenomena, they made singular contributions to a new view of knowledge and information. And in one dimension, this was decidedly not just an urban matter.

AGRICULTURAL REVOLUTION

This term is now out of favor. Earlier historians, inspired by the revolutionary change in industry later in the 18th century, saw a comparable set of changes in agriculture at the beginning of the century. Now the consensus of historians is that although there were indeed very important improvements, they were spread out over a very long time, were not adopted for all cultivation, and are very difficult to measure accurately. Given those qualifications, it is undeniable that England (and other parts of Britain) ended famine by the middle of the 18th century, feeding a population that grew very rapidly for the next century even as large numbers of the farming population migrated into the growing new industrial towns.

Some of the change was due to technical experimentation: new patterns of crop rotation, some borrowed from Dutch farming; the use of fertilizers, such as marl (a clay soil rich in lime); and mechanical inventions, like Jethro Tull’s seed drill. Food supply was made more manageable with the growth of better inland transportation, e.g., the turnpikes that began to expand in 1730, then canals, and, much later, railroads.

One factor long held to be critical was the movement to enclose open fields. These fields had been cultivated for centuries on a system of strips held by different tenants who did the major work in common and shared the product. Also, woodland and common pasture under this older system were part of the design. Such common lands had no discernible legal title, and in order to reallocate them it was necessary to obtain an act of Parliament to create a title and dispose of it. Thus, private enclosure acts became a common event. Their numbers grew quickly in the later 18th century, and they may have increased the pace of change, because those landlords seeking enclosure were usually the ones intent on using newer methods as a means to increase output.

The most important ingredient in agricultural growth was reminiscent of some features of the Enlightenment: empirical study, sharing of information,

A New Society 49

and stimulation of “improvement.” Progressive landlords used this term to describe themselves. One of the more famous, Thomas Coke of Norfolk, organized meetings at his estate, conducted experiments in crop rotation and livestock breeding, and gave incentives to his tenants to adopt the changes. In the farmer’s notoriously conservative environment, he and others promoted a wide range of improvement. Of course, the forces of an expanding market provided a traditional incentive that all farmers understood.

Growth in the British population was a striking feature of the later 18th century. There had actually been a leveling or decline in population in the late 17th century. Then, after four or five decades of slow growth, a large increase began around the 1780s. Historians and demographers who have studied the process intently have not found a dramatic explanation for the rise. Several factors produced a drop in death rates (especially among young children) and an accompanying increase in the birth rate. There was no single trigger, but some of the causes included better diet and better medical care (including inoculation against smallpox) and the disappearance of plague (the last outbreak was in 1665; cholera would revive the horror in the 1830s). Probably most important was an increase in fertility rates, i.e., earlier and more numerous marriages. This change could be caused by higher earnings and changes in living patterns: whereas farm workers might have lived in a single enlarged household, urban and industrial workers might more often have had separate dwellings or apartments. Whatever the explanation, the consequence was that population in England and Wales nearly tripled in the century after 1750. In the same period Scotland’s rose by 130 percent and Ireland’s population, up to 1846, increased by 450 percent.

To the extent that there was an agricultural revolution, those who profited most from it were an agrarian ruling class of peers and gentry who owned most land and leased it to tenant farmers. Parliament’s business was very much tied to the land in 1700, and that business was done by members of this class. The land was taxed—an innovation to pay for William III’s wars—and other burdens of government fell on the landowner, who was responsible for local government (the commission of the peace; the militia; and county offices such as sheriff, service on grand juries, etc.) However, the landowning class was about to meet its greatest social and political challenge, as the small corps of professional people and merchants of the 17th century was transformed into a much enlarged middle class—great colonial merchants known as nabobs, bankers and brokers, factory owners and industrialists—who created a new capitalist layer in the social hierarchy.

TRADE AND INDUSTRY

Those people once called the “middling sort” were a small group in the old society, one that enjoyed better incomes than the laboring poor as well as some social standing. This was particularly true for the more notable professionals and traders. By the middle of the 19th century their numbers would explode, along with their aggregate wealth. The reasons for this growth were

50 Great Britain

the creation or mobilization of capital; the expansion of trade, especially overseas; growth of industrial production; and the creation of a consumer society.

Some economic historians speak of a “financial revolution” at the end of the 17th century. This is more than an attempt to echo the better-known industrial revolution. Vast amounts of money were raised to fight William III’s wars, much of it raised by loans through the Bank of England, with the government paying 8 percent annual interest. In London and the provinces, banking grew steadily. Stock exchanges facilitated the link between shareholders and entrepreneurs and employed armies of agents and solicitors. Landowners and merchants continued to invest in government bonds but also lent increasing sums to underwrite shipping, road building, and canals. This capitalization was essential to the coming age of industry.

No less essential to economic growth was the expansion of England’s (and later Scotland’s and Ireland’s) trade. From the latter days of the 17th century, the contest for imperial trade went more and more in Britain’s favor, while the conditions of internal trade in the British Isles offered a cooperative marketing structure. The two components reinforced each other. The wars of the period 1756–1815 secured Britain’s place as the leading international trader. The cost of war was high, but the gains for commerce outweighed the losses. Imports and exports increased by 500–600 percent, most notably in imports of raw materials and exports of manufactured goods. Particularly important in these areas were colonial markets, including the West Indies, India, and the onetime American colonies. The share of national income from overseas trade doubled in the 18th century.

Internal trade grew as well. The previously noted transport improvements in roads and canals, plus improvements in river navigation, helped the movement of goods. By the 1830s there were 22,000 miles of turnpikes and 4,000 miles of canals in use. These connections helped the growth of towns in England and Scotland. Most towns had been small, with only a few over 5,000. The 18th century saw a doubling in the share of population living in such larger towns. London remained an outsized exception, growing still more in this period, but alongside it grew major trading centers and new manufacturing towns. In the 1851 census there were 63 towns with more than 20,000 inhabitants, whereas in 1801 there had only been 15. By mid-century the urban population was about 50 percent of the total; it had about half of that in 1700.

Another factor in Britain’s favor was that the island constituted the largest free-trade area in Europe: most continental states had tariff barriers and border limits to trade. It may be that this feature was one of the stimulants to a radical new theory of economics. The idea of free trade was promoted by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, notably in his Inquiry into the Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). His thinking was that the effect of regulation must be to limit trade; and while some circumstances (war, famine, and natural disasters) might require government intervention, the general unregulated dealings of merchants and customers ought to produce the most benefit to all. This statement of what came to be called classical economics marked the opening of a new phase in British economic thinking. It was only slowly incorporated into gov-

A New Society 51

ernment policy through extended debates in many areas. But by 1850 the corn laws, navigation laws, and other restrictions had been repealed, and Britain had begun a new era of “free trade.” Some accounts suggest this was the core of an age of laissez faire, or noninterference by government. Though that became a slogan for many and a social philosophy for others, the performance of British governments presented a mixed picture of regulation and distance.

The most studied feature of British society in the 18th century was the rise of industry—the “industrial revolution.” Historians are now retreating from this usage, but its essential point has validity. There was a massive shift in employment, production, and creation of wealth, from older agricultural sectors to that of industry. This process took more than a half-century (approximately from 1780 to 1830), but it was an undeniably major change. The earlier 18th century witnessed a scattered number of innovations: in coal production (1720s), iron manufacture (1730), and textiles (1760–80). After the 1780s, improvements in steam engineering (James Watt) and the manufacture of iron (Henry Cort and John Wilkinson) and textiles (Richard Arkwright) launched a new wave of growth. By the 1830s a large portion of the industrial workforce worked in factories, their location concentrated in some of the new towns.

The classic image of the factories as “dark satanic mills” is overstated, but it conveys one contemporary reaction, and it suggests the likelihood of a social response sympathizing with the new worker’s hard lot. But just as much sympathy should go to the obsolescent handloom weavers of the 1800–30 period, and the dynamic of workers’ complaints was enhanced by

English textile factory, 1877

(Hulton/Archive)

52 Great Britain

their collective presence in the new workplace. What this meant in terms of ammunition for reforms will be examined in the next section. What the output of factories meant for society as a whole was to provide one more impetus to a consumer revolution.

Leaving aside the question of pace, it is acknowledged by recent historians that this period witnessed a radical change in spending and consumption. There was a sufficient increase in income levels in the 18th century to provide the means for many members of society to obtain goods that were simply not available to many before 1700. Household furnishings, clothing, and luxury items were all in conspicuously greater supply in the course of the period, and Britain had, by comparison, far more of all of these than other countries in Europe. In addition, along with the rise in quantity came a new environment of acquisition: mass production, promotion, and competition became basic features of the consumer society. Moreover, the inequalities that were bound to occur, plus the awakened demand accompanying these changes, must have played a part in responses to those truly revolutionary events—in 1776 and 1789—which marked the later years of the period.

REVOLUTION AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Political revolutions in the later 18th century had important effects on British society and government. Basically, the upheavals in America and France put British institutions under the microscope and added significant pressure to existing ideas for reform. The consequence was a series of changes that helped to transform society by 1850. By then society was aware of and responding to the first coherent demands of its “working class.”

To understand the events of this period, an outline of its politics is necessary. The War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13) ended with the Treaty of Utrecht, which confirmed Britain’s imperial gains in 1713. At home the main issue was the royal succession. Pursuant to the 1701 Act of Settlement, when Queen Anne died in 1714, George I (eldest son of the electress Sophia of Hanover) succeeded her. After taking the throne in 1714, he insisted on Whig ministers, believing that all Tories were supporters of the Jacobite cause. That movement brought on a Jacobite rebellion in 1715, which was crushed by royal troops, and the last in 1745, with the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie at Culloden in 1746. Whigs were able to capitalize on the threat to prove their loyalty. In 1721 Robert Walpole became the king’s first minister, and he continued in that post when George II came to the throne in 1727. Walpole’s main achievement was a long period of peace, reducing the demands of the land tax while showing skill in managing the government’s finances. But part of that skill was in the use of patronage, for which he was both feared and admired. After the outbreak of war with France in the 1740s, he was removed from office, and the king turned to Walpole’s lieutenant, Henry Pelham. By the later 1750s, the Seven Years’ War brought William Pitt to the post of first minister. He was forced to resign in 1761 just after George III came to the throne. That king began his long reign (1760–1820) by relying on his former tutor Lord Bute as chief minister. This odd

A New Society 53

choice opened a period of instability, and there was a quick succession of ministers until Lord North assumed control in 1770. His government would last until 1782, though North often tried to resign during the American Revolution.

The war in America was precipitated by Britain’s efforts to make the colonies pay for their defense, first with the Stamp Tax (1765) and then with tariffs on colonial trade. Resistance to this policy finally generated a colonial rebellion, which British troops attempted to suppress, but George Washington led a successful campaign to defeat the forces of the Crown. After victory (1781) and a peace treaty (1783), the 13 colonies became independent. This crisis naturally caused serious repercussions: Britain’s colonial policies were severely criticized, and the Colonial Office was temporarily abolished. But there was still keen interest in colonial development, particularly in the Pacific, the Caribbean, and Africa. In domestic affairs, the loss of American colonies brought on a period of angry debates over government failure; election reform, finances, and colonial policy were all disputed.

During the crisis in 1783, the king removed his ministers and selected William Pitt (the young son of the former chief minister) as leader of the government. Pitt won an election in 1784 and went on to serve the Crown for the rest of the century. He put forward a mix of progressive policy (reducing sinecures, carefully managing finances) and conservative philosophy (crackdowns on sedition, vigorous monitoring of critics of the Crown). Pitt was in office when the French Revolution broke out. He and others did not sense its danger at first, and indeed, he thought there was no likelihood of war; but France, having disposed of her king, declared war on Britain in 1793. Pitt had to gather a coalition of European states (the first of four), which he subsidized with British money while using the British fleet to control the seas.

Pitt was forced to resign in 1801, after the king rejected his plan for an act of union with Ireland. Pitt wanted to include Roman Catholics in the settlement, but the king refused. The plan of union was a reaction to the Irish rebellion in 1798, which was supported by a small amount of French assistance. That created a fear of future assault on England and the chance of being surrounded. Union also addressed the fear of the minority Anglo-Irish population toward the Catholic majority.

War continued in 1802 with a new opponent in Napoleon Bonaparte, the feared revolutionary general and, later, emperor. His plan for an invasion of England was made impossible by Admiral Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar (1805). But Napoleon still conquered most of Europe, faltering only when he tried to conquer Russia (1812). His final defeat by Wellington at Waterloo (1815) marked the ascendancy of Britain in European and world politics. A period of 40 years of peace for Britain followed, though there were several serious bouts of revolution on the continent.

At home in Britain there was great distress in 1815. Heavy taxation, agricultural depression, loss of foreign trade, and massive military commitments all made of life more difficult. After the war there were riots and demonstrations, both being met with government force (Spa Fields, 1816; Peterloo, 1819). Later, limited economic improvement was paralleled by an increase in the number and

54 Great Britain

intensity of supporters of a wide range of political, social, and economic reforms. A cluster of debates and decisions put the finishing touches on the new society by 1850.

Since the later 18th century there had been mounting criticism of the system of parliamentary representation. In the rural areas there were fairly large electorates, as the vote was granted to owners or occupiers of land worth 40 shillings per annum—a level set in the fifteenth century. In the boroughs (old townships with the right to send a member to Parliament), some electorates might be very large, but many had become small or even nonexistent. The latter “rotten” boroughs were under the control of landowners who could decide the member who would sit in the House of Commons. As early as the 1780s there had been a movement among county gentry to transfer some of these seats to the counties, thus obtaining more representative membership. This movement was swept aside in the 1790s, but criticism of the old order mounted. In 1830 a new ministry undertook reform, though it took two years, plus much debate and pressure, before the important reform was enacted. In 1832 the vote was given to all those who held property worth £10 per annum, and a number of the rotten boroughs lost their seats, which were transferred to new towns that had had no members. Bills were passed for England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. The greatest increase in voters was in Scotland, the smallest in Ireland.

In none of these cases, however, was there an effort to go beyond the principle of representation for property owners. This clearly left out the vast majority of the population. In 1836 the London Workingmen’s Association was organized to press for universal manhood suffrage. This was the root of the Chartist movement, so called for its main document, “The People’s Charter,” which called for votes for all males and the conversion of Parliament into a genuine democratic assembly. This document was presented to Parliament on several occasions in petition form, but it was rejected every time. These failures discredited the moderate reformers, and more radical approaches were proposed. Though the movement ended in 1848, almost all of the charter’s points were made law by 1910.

Social reforms were also put forward, again with roots in the 18th century. Many of these were the result of agitation by “evangelical” reformers—those who wanted, in keeping with holy scripture, to remedy what were seen as immoral policies. The first major target of the movement was the slave trade, and a 20-year agitation resulted in an act abolishing that trade in 1807. The next target was slavery itself, which was abolished in the British Empire in 1833. There were also dedicated secular reformers, most notably the followers of Jeremy Bentham, known as utilitarians. Their aim was to introduce reforms for the “greatest good for the greatest number.” Among other things, utilitarians supported reform of prisons, criminal law, and the poor law. The latter was the system of parish support for the able and disabled poor. This had been instituted on a national basis in the Elizabethan era, but it had become extremely costly during years of economic stress at the turn of the century. Thus many, especially ratepayers, were anxious to introduce a new system. A controversial act in 1834 tried to do just that, but it had mixed results. Meanwhile a serious

A New Society 55

crisis in public health arose in 1832 with the outbreak of cholera, which took 31,000 lives. There was serious debate on the means of preventing such epidemics, and after many hearings and discussions, the first general public health laws were enacted.

In another closely related category, the conduct of economic life came into the purview of legislators in several ways. Worker efforts to organize and protect their livelihood were challenged by Combination Acts (1799, 1800). Any combination, or union, in restraint of trade (by employers or workers) was illegal in common law, but Parliament chose to invoke special enforcement provisions against workers. After two decades of campaigning, these acts were repealed in 1824, allowing an increase in legal organization by workers. There were also significant reforms in the workplace. Conditions for factory workers were a matter of serious complaint, and as early as 1802 there was some legislation. The title of the first act was a sign of the times: the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act was aimed at protecting young workers from poor conditions in contemporary factories. There were more real dangers—from long hours of work, from dangerous machinery, and from unscrupulous employers. A roster of reforms came forward, especially after 1830. Another area of economic reform was the campaign to abolish the “corn laws,” which were protective tariffs on various grains. The laws were enacted during the French wars to encourage cultivation of marginal land and were kept after the wars at the request of landowners. They were not beneficial to consumers, especially poor workers. In 1839 a group of progressive manufacturers organized the Anti-Corn Law League. This was a new type of pressure group, with well-funded and well-orchestrated campaigns, touring speakers, publications, and an intense lobbying effort in Parliament. The league targeted Robert Peel, the conservative leader, as the laws’ chief supporter, but ironically it was he who, in the Irish Famine crisis of 1846, pushed through the repeal. This was followed soon after by repeal of the navigation laws—and the beginning of the era of free trade in Britain.

In 1851 the census revealed that Britain had become 50 percent urban. It also took measurements of religious observance for the first (and only) time. The results of that tabulation were very disturbing. Less than half the population was attending church at some time on Sunday. Tallies of the several different congregations revealed that dissenters outnumbered Anglicans; and Catholics, whose worship had been lately recognized as lawful, showed significant attendance. The society glimpsed in that census was vastly different from the early 18th century. It boasted a broad and wealthy middle class and a literate and demanding working class. Those two would no longer accept the old regime; indeed the reforms of the last generation pointed to further change ahead. And this society, growing rapidly and sending its products across the globe along with missionaries and merchants, was fast becoming the leading imperial power. That fact would shape the new society of the late 19th century.