A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

Taung Site of the discovery of the type specimen

of AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFRICANUS in 1924, close

to the town of Taung, N. Cape Province, South Africa. The site consists of four superimposed travertine aprons (with associated breccia and conglomerate deposits) banked against the Gaap escarpment. The Taung skull and associated fossils came from sediments filling a cavern system eroded in the oldest (Thabaseek) travertine, probably contemporaneous with the next younger (Norlim) travertine. Attempts to derive radiometric dates for the Taung skull are considered inconclusive, and estimates based on faunal remains vary between 2.3 and 1.8 million years.

K.W. Butzer: ‘Palaeoecology of South African australopithecines: Taung revisited’, CA 15 (1974), 367–82; P.V. Tobias, ed.: Hominid evolution: past, present and future

(New York, 1985), 25–40, 189–200.

RI

Ta-wen-k’ou (Dawenkou) Neolithic culture named after the type-site near T’ai-an, in the Shantung region of China, which is sometimes referred to as the Ch’ing-lien-kang culture (a red pottery culture investigated in 1951 at the type-site of this name, in Huai-an-hsien, in northern Chiang-su). Over a hundred Ta-wen-k’ou culture sites are known, mainly distributed in central and southern

TAXILA 565

Shan-tung and northern Chiang-su; clusters of radiocarbon datings range from 5500 to 3500 BC. The culture is more or less contemporary with YANG-SHAO to the west in the Huang-ho River Basin, Ma-chia-pang and HO-MU-TU to the south in Chiang-su and Che-chiang, and TA-PEN-K’ENG in the southern coastal region of Fu-chien, Kuangtung, Kuang-hsi and western Taiwan.

For the most part the Ta-wen-k’ou predates the LUNG-SHAN culture. Agriculture was practised, as suggested by millet grains found in several sites and the presence of sickles of bone, tooth and shell. A large variety of animal bones including the domestic pig, cattle, deer, alligator, turtles, chickens, fish, molluscs and snails bear witness to the diet and hunting and fishing activities, as well as providing an indication of the more humid and warmer lacustrine environment of the time. Houses were of the round semi-subterranean type, some square, and with postholes, but only a few have been found.

Anon.: Ta-wen-k’ou (Peking, 1974); Chang Kwang-chih:

The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven, 1986), 156–69.

NB

Taxila Large urban site located near modern Rawalpindi in northern Pakistan alongside a major

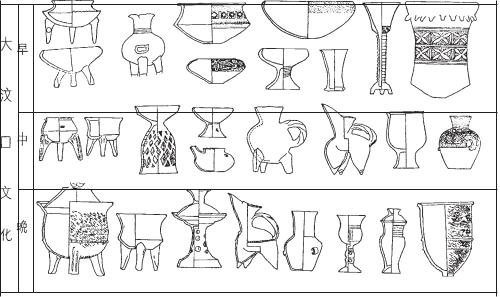

Figure 54 Ta-wen-k’ou Division of the Ta-wen-k’ou culture into three phases as reflected in the pottery styles. Source: Anon.: Ta-wen-k’ou (Peking, 1974), fig. 91.

566 TAXILA

route between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. First excavated by A. Cunningham in the 1860s, it consists of several mounds (Hathial, Bhir, Sirkap and Sirsukh), not all of which were occupied at the same time. The occupation levels, dated primarily by numismatic evidence, stretch from the ACHAEMENID period (c.516 BC) to the 3rd century AD. Although Greek textual sources document the arrival of Alexander the Great at Taxila in 326 BC, definitive archaeological evidence of his brief occupation has yet to be identified.

During the MAURYAN PERIOD (c.321–189 BC) the city of Taxila was a major political centre, first under the Mauryan empire and later under autonomous rulers. Indo-Greek occupation of the city began in the early 2nd century BC, and it was during this period that the construction of the walled city of Sirkap was initiated (but see Erdosy 1990 for a different perspective). The next occupants of Taxila

were the Sakas (SCYTHIANS) and PARTHIANS

(c.90 BC–AD 60; Erdosy 1990: 668). The mound of Sirsukh is associated with subsequent Kushana occupation of the city (c.AD 60–230), during which many of the Buddhist monasteries were expanded and GANDHARAN-style sculpture flourished. Excavations have revealed dense architectural remains, including Buddhist STUPAS and monasteries, and a wide array of ceramic, copper and iron goods, as well as sculptures and ornaments of gold, silver and other precious materials.

J. Marshall: Taxila, 3 vols (Cambridge, 1951); A.H. Dani: The historic city of Taxila (Paris, 1986); G. Erdosy: ‘Taxila: political history and urban structure’, South Asian archaeology 1987, ed. M. Taddei (Naples, 1990), 657–75.

CS

Tayma see ARABIA, PRE-ISLAMIC

tazunu see AFRICA 5.3

technocomplex Term used to describe a group of cultures which are characterized by assemblages sharing a polythetic range. Each of the cultures in the group has different specific types of the same general family of artefacts, but they all share a widely diffused and interlinked response to common factors in environment, economy and technology.

D.L. Clarke: Analytical archaeology (London, 1968).

KM

Tehuacán Arid highland valley in Puebla, south-central Mexico, where a series of caves and

open-air sites provided evidence for the history of domestication and the beginnings of sedentism in Mesoamerica between c.7000 and 2300 BC. The valley continued to be occupied during Classic and Postclassic periods (c.AD 300–1521).

D.S. Byers, ed.: The prehistory of the Tehuacán Valley, I: environment and subsistence (Andover, 1967).

PRI

Teishebaina see URARTU

Tekkalakota Neolithic site located in an area of granitic hills in modern Karnataka, southern India. The excavations of M.S. Nagaraja Rao in 1963–4 defined two chronological periods (Phase I, 1700–1600 BC and Phase II, 1600–1500 BC) and revealed well-preserved foundations of circular huts as well as large quantities of faunal remains, including domestic cattle, sheep, deer and rodents. The botanical remains indicate that horse gram (Dolichos biflorus) was being cultivated.

Artefacts excavated at Tekkalakota include handand wheel-made ceramics, beads, copper implements and gold ear ornaments. Seven burials were excavated: six from phase I and one from Phase II. In Phase I partially disarticulated adult skeletons were buried in shallow pits covered with stones, while children were buried in ceramic urns. The Phase II burial comprised the extended body of an adult associated with

and plain red ceramic vessels. Nearby rock-shelters contain petroglyphs and wall paintings depicting bulls, dogs, and humans, interpreted by Nagaraja Rao and M.C. Malhotra (1965: 98) as dating to the Neolithic period.

M.S. Nagaraja Rao and M.C. Malhotra: The Stone Age hill dwellers of Tekkalakota (Pune, 1965); B.P. Sahu: From hunters to breeders (Delhi, 1988), 189–91, 225–6.

CS

tell Arabic term used to describe the distinctive stratified mounds of archaeological deposits which formed on the sites of early settlements, particularly in Western Asia, southeastern Europe and North Africa. Tell sites accumulate vertically because of the repeated demolition and re-levelling of mudbrick houses over the course of long periods of time. Probably the earliest examples are to be found in the Jordan valley, including the town of JERICHO, where the Proto-Neolithic strata form a 10-metre high mound. The word ‘tell’ can be traced back to tilu, the AKKADIAN word for mound. The equivalent words used to describe such town-mounds in

Egypt, Persia and Turkey are kom, tepe and hüyük respectively.

Despite the growth of interest in

ARCHAEOLOGY and LANDSCAPE STUDIES during

the 1980s and 1990s, only a small number of specific tell sites, e.g. SITAGROI (Davidson 1976), LACHISH (Rosen Miller 1986) and AXUM (Butzer 1982: 93–7, 142–5), have been studied explicitly in terms of

their SITE FORMATION PROCESSES. Arlene Miller

Rosen (1986: 1) points out that there is still ‘only a vague understanding of the processes by which tells form and why tells develop from some urban sites and not others’, but her own research, involving a combination of MICROARCHAEOLOGY, mud-brick analyses and the study of the processes of erosion, has provided a good scientific basis for future work. Wendy Matthews’ use of micromorphology at ABU SALABIKH has proved to be a promising means of determining the original functions of specific rooms within a tell site (see Matthews and Postgate 1994).

D.A. Davidson: ‘Particle size and phosphate analysis: evidence for the evolution of a tell’, Archaeometry 15 (1973), 143–52; ––––: ‘Processes of tell formation and erosion’,

Geoarchaeology: earth science and the past, ed. D.A. Davidson and M.L. Shackley (London, 1976), 255–66; K.W. Butzer: Archaeology as human ecology: method and theory for a contextual approach (Cambridge, 1982); A. Miller Rosen: Cities of clay: the geoarchaeology of tells

(Chicago, 1986); W. Matthews and J.N. Postgate: ‘The imprint of living in an early Mesopotamian city: questions and answers’, Whither environmental archaeology?, ed. R. Luff and P. Rowley-Conwy (Oxford, 1994).

IS

Tell (el-) For the purposes of alphabetization, the word ‘Tell’ is disregarded, e.g. see HASSUNA, TELL.

Telloh (anc. Girsu) City site in southern Iraq, 48 km north of Nasriya, which was the first Sumerian site to be scientifically excavated (see SUMER). Although initially misidentified as the city of LAGASH, it is now known to be Girsu, an important cult centre of the god Ningirsu during the Lagash Dynasty (c.2570–2342 BC), located about 20 km from the site of Lagash itself (Tell el-Hiba). It was first investigated in 1877–1900 by Ernest de Sarzec, who discovered thousands of cuneiform tablets bearing important texts regarding the history and socio-economic structure of the Lagash Dynasty but succeeded in destroying much of the architecture through failing to identify unbaked brick structures.

The later excavations of Georges Cros (1903–9), Henri de Genouillac (1928–31) and André Parrot (1931–3) were more fruitful. One of the most

TEOTIHUACÁN 567

important monuments from Telloh is the so-called Stele of the Vultures (now in the Louvre), which records a series of disputes over water between the states of Lagash and Umma in the reign of Eanatum of Lagash (c.2440 BC). The earliest settlement at the site dates to the late Ubaid period (c.3800 BC) but it reached its peak during the 3rd millennium BC. Temporarily subdued by the Akkadians in the late 3rd millennium BC, the state of Lagash underwent a brief renaissance under Ur-Bau and his successor Gudea, during the late Gutian period, c.2200–2150 BC. Apart from the huge brick mausoleum of Urningirsu (Gudea’s son) there are few surviving buildings from this period, but the renewed prosperity at Girsu is best indicated by the magnificent diorite statues of Gudea, more than twenty of which have been excavated at Telloh. The city maintained a certain degree of importance during the early 2nd millennium, but it was eventually abandoned in the late 18th century BC and there was no further occupation until the Parthian period (c.250 BC–AD224).

L. Heuzey: Découvertes en Chaldée, 2 vols (Paris, 1884–1912); G. Cros, L. Heuzey and F. Thureau-Dangin: Nouvelles fouilles de Tello, 2 vols (Paris, 1910–14); H. de Genouillac: Fouilles de Tello, 2 vols (Paris, 1934–6); A. Parrot: Tello, vingt campagnes de fouilles (1877–1933)

(Paris, 1948).

IS

Temple Mound Period Rarely-used term pertaining to the MISSISSIPPIAN period. It refers to the presence of flat-topped, rectangular earthen mounds at large Mississippian sites distributed throughout the southern Midwest and Southeast of North America. These mounds served as platforms for buildings, including so-called temples or mortuary houses that contained the bones of the ancestors of highly ranked people.

G.R. Willey: An introduction to American archaeology I: North and Middle America (Englewood Cliffs, 1966).

GM

temple mountain Architectural term used in southeast Asian archaeology to refer to structures built to house the god-king’s cremated remains and to serve as a temple to him after his death. The tallest surviving examples are at ANGKOR Wat in Cambodia.

Tenochtitlán see AZTECS

Teotihuacán Located in an arid valley northeast of the BASIN OF MEXICO, near modern Mexico city, this massive Late Formative and Classic city

568 TEOTIHUACÁN

Pyramid of the Moon |

Pyramid of the Sun |

Ciudadela |

Street of the Dead |

Temple of Quetzalcoatl |

Figure 55 Teotihuacán Isometric view of the ceremonial structures lining the main north-south axis of Teotihuacán, known as the Street of the Dead. Source: M.E. Miller: The art of ancient Mesoamerica (Thames and Hudson, 1986), fig. 41.

exerted a profound influence on the development of many of the later cultures in Mesoamerica. Teotihuacán covers an area of about 20 sq. km; its total population has been estimated at about 125,000 people or more during its Classic peak around AD 300–500. The principal centre of a powerful highland state, Teotihuacán began its dramatic growth in the Late Formative period, with most major construction in the city completed by c.AD 150. The city’s enormous size and the difficulty of understanding the complex factors leading to its rise and fall have posed enormous challenges to archaeological research; these have been exacerbated by modern occupation and disturbance of the site. Two ambitious projects of survey and settlement pattern analysis combined mapping and surface collection of artefacts in an investigation of the site’s history. One project was directed toward the processes of urbanization and growth of the city itself (Millon 1973) and the other addressed Teotihuacán’s role in the larger basin context (Sanders et al. 1979). More recent work has explored the social and ideological factors underlying the site’s structure (Sugiyama 1993).

Teotihuacán exhibits a strikingly integrated site plan laid out on a regular grid of streets. Major civic-ceremonial architecture is arranged along a broad avenue stretching some 2 km north-south, known as the Street of the Dead. At the north end is a large terraced pyramid known as the Temple of the Moon; on the east side is another terraced pyramid known as the Temple of the Sun. The Sun temple sits above a natural cave in the bedrock, believed to have been a sacred location that probably determined the temple’s siting. South of

the Sun Temple is a huge square enclosure, the Ciudadela, with a large temple on its east side; across the avenue is another enormous enclosure that might have served as a market. Recent work around the Temple of Quetzalcoatl in the Ciudadela (Cabrera et al. 1991) has shown that the structure was built in a single phase of construction accompanied by the sacrifice and burial of perhaps 200 individuals. The temple-pyramids at Teotihuacán were built in characteristic TALUD-

TABLERO style.

All around this civic-ceremonial core is a dense arrangement of buildings, including perhaps as many as 2000 multi-family apartment compounds. Residents of these compounds may have been linked by family (lineage) ties, and may have shared occupational specialities, as particular compounds seem to have concentrations of artefacts associated with pottery making, for example, or woodworking. Compounds associated with wealthier families were decorated with beautiful, brightlycoloured murals showing religious scenes.

There is abundant evidence for obsidian working at the Teotihuacán apartment compounds. One of the explanations offered for the dramatic size and influence of Teotihuacán throughout Classic period Mesoamerica is that the city controlled the exploitation and distribution of two or more valued sources of obsidian for tool-making. Other explanations focus on the many springs in the otherwise dry Teotihuacán valley: these were incorporated into irrigation systems, which increased agricultural yields by permitting water to be delivered to crops before the normal rainy (planting) season and by allowing crops to mature

before the first frosts in this relatively cold, highaltitude region.

The language spoken by Teotihuacános is unknown, although it may have been Totonacan. Unlike other contemporaneous areas of ‘prehistoric’ Mesoamerica, no written texts have been found at Teotihuacán; the city’s art – known primarily from murals – is ahistorical and lacks reference to dates and events. Similarly little is known about Teotihuacán’s political organization: it is uncertain whether the city and state were governed by a divine king or secular leaders.

Teotihuacán engaged in widespread trade with other areas of Mesoamerica, obsidian and CACAO being two of the principal goods involved. Teotihuacán influence is seen as far away as the LOWLAND MAYA area in architectural styles, sculptural motifs (e.g. representations of the rain-god Tlaloc) and pottery vessels such as cylinder tripods.

Between AD 550 and 650 Teotihuacán began to experience disruptions in its architectural and population growth, as well as a retraction of its ties to other areas of Mesoamerica. Toward the end of this period archaeological investigations have revealed signs of conflict at the city, including destruction of temples and extensive conflagrations. The reasons for these disruptions are unclear, but Teotihuacán apparently underwent a major ‘collapse’ or decline around AD 750. The population of the city is estimated to have dropped to approximately 30,000 persons. At about the same time that Teotihuacán was experiencing difficulties, sites around the periphery of the basin of Mexico, such as Tula (see TOLTECS) and CHOLULA, began to flourish. Teotihuacán was never completely abandoned, however, and during Late Postclassic times the city had a population of approximately 80,000 persons; some AZTEC legends claimed that Teotihuacán was the place of creation of the sun and moon gods and the names of its principal temples are those used by the Aztecs.

R. Millon: Urbanization at Teotihuacán, Mexico, I: The Teotihuacán map (Austin, 1973); W.T. Sanders et al.: The basin of Mexico: ecological processes in the evolution of a civilization (New York, 1979); R. Cabrera et al.: ‘The templo de Quetzalcoatl project at Teotihuacan’, AM 2 (1991), 77–92; S. Sugiyama: ‘Worldview materialized in Teotihuacán, Mexico’, LAA 4 (1993), 103–29.

PRI

tepe see TELL

tephrochronology The use of chemically

TEPHROCHRONOLOGY 569

characterized layers of volcanic glass particles (tephra) as stratigraphic markers for correlating one location with another: historical dating of the eruption or other dating evidence (e.g. RADIOCARBON DATING on associated peat layers) provides a reference chronology. The technique has been used in northwestern Europe, the United States of America and the Far East.

In northwestern Europe, for example, the tephra layers are largely from Icelandic eruptions; in Britain no other source has been identified. The tephra are air-borne particles (typically 200 μm) that are most heavily deposited by rainfall over high ground; thus the incidence of tephra layers in Scotland is high, but peters out further south in Britain. The deposition of these layers is rapid and their distribution is wide (up to 2000 km); each provides a synchronous marker over a potentially large area (northern Britain, northern Germany, central and southern Scandinavia for the Icelandic tephra). Not all eruptions will necessarily be represented at each locality, however, depending on the size of the eruption and meteorological conditions (nearly 80 layers have been identified in Iceland for the Holocene period compared to some 20 in Scotland and about 12 in Northern Ireland).

It has been shown that tephra from volcanoes in a relatively restricted locality have distinct petrological and chemical characteristics, definable by optical microscopy (e.g. refractive index and birefringence) and analysis in the electron microprobe respectively: many are characterized by analysis alone. The study of tephra layers generally concentrates on those in peat bogs and lake sediment where the record is more continuous than for other terrestrial sediments. Their presence is identified by X-radiography of columns or cores. The direct association of these marker layers with pollen sequences provides the opportunity to study environmental change on both a regional and broader basis.

Apart from a small number of historically recorded eruptions (e.g. Hekla 1 in AD 1104), the dating of tephra layers has largely been by radiocarbon dating of associated organic material: high-precision radiocarbon dating and MATCHING have provided calendar dates to within a decade or two. Large eruptions have an effect on tree-ring size, but there is no direct means of correlating a specific eruption with the particular episode of reduced growth. The occurrence of tephra in ICE CORES, however, has the potential to provide another dating source. Research has been undertaken in the 1990s to identify Icelandic tephra in the Swedish VARVE sequence which would provide

570 TEPHROCHRONOLOGY

dates to the nearest year for those eruptions represented.

A.J. Dugmore: ‘Tephrochronology and UK archaeology’, Archaeological sciences, ed. P. Budd (Oxford, 1991), 242–50.

SB

terminus ante quem (Latin: ‘end before which’) Phrase used to describe a situation where it can be assumed that a piece of archaeological evidence dates to a period earlier than a certain date. In terms of stratigraphy, it is possible to assign a terminus ante quem when the deposit in question is sealed by, or cut through by, one or more datable features. If a building can be assigned a secure date, e.g. AD 1300, then it can be assumed that any layers through which its foundation trenches cut must have a terminus ante quem of AD 1300. See also

CROSS DATING.

P. Barker: Techniques of archaeological excavation, 2nd edn (London, 1982), 197–200.

IS

terminus post quem (Latin: ‘end after which’) Phrase used to describe a situation where it can be assumed that an archaeological feature or deposit was formed on or after a certain date. Thus, the presence of a coin of the emperor Augustus in the lowest stratum of a Romano-British settlement would suggest a terminus post quem of the 1st century AD for the foundation of the town (i.e. the deposit could not have been formed earlier than that date but it could be later). See also CROSS

DATING.

P. Barker: Techniques of archaeological excavation, 2nd end (London, 1982), 197–200.

IS

Ternifine Pleistocene artesian lake site (now known as Tighénif) 20 km east of Mascara, northwestern Algeria, discovered in 1872 when a sand pit was opened by the side of a Muslim cemetery; the floor of the sand pit was excavated to a depth of 7 m beneath the water table by Camille Arambourg and R. Hoffstetter in 1931 and 1954–6, and, after a considerable lowering of the water table, again by a Franco-Algerian team in 1981–3. Faunal remains and ACHEULEAN artefacts were found at the base of the sands and in a greyish clay layer with carbonate nodules, above sterile varicoloured clay which formed the bed of the lake. On faunal grounds (supported by PALAEOMAGNETIC measurements) the site is considered to belong to the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene, about 700,000 years ago.

Three adult human mandibles and one parietal found together with the other remains (as well as a number of isolated teeth, four of which are now thought to have belonged to a child) were attributed by Arambourg to Atlanthropus mauritanicus, but he recognized their similarity to the hominids from CHOUKOUTIEN, and they are now generally classified as HOMO ERECTUS. As such they still constitute the earliest hominid remains known from North Africa.

C. Arambourg and R. Hoffstetter: Le gisement de Ternifine (Paris, 1963); M.H. Day: Guide to fossil man, 4th edn (London, 1986); D. Geraads, J.J. Hublin, J.J. Jaeger, H. Tong, S. Sen and P. Toubeau: ‘The Pleistocene hominid site of Ternifine, Algeria: new results on the environment, age, and human industries’, Quaternary Research 25 (1986), 380–6.

PA-J

‘terracotta army’ see CH’IN

terra preta South American form of ‘black earth’ consisting of the dark fertile soils of anthropic origin found along the Amazon and its tributaries.

M.J. Eden, W. Bray, L. Herrera, and C. McEwan: ‘Terra preta soils and their archaeological context in the Caquetá Basin of Southeast Colombia’, AA 49/1 (1984), 125–40.

KB

Teshik-Tash Palaeolithic (MOUSTERIAN) cave site in southern Uzbekistan, in the Baisuntau Mountains, in the valley of Turgan-Darya. Discovered in 1937 by A.P. Okladnikov, who

Figure 56 Teshik-Tash Reconstruction drawing of the head of a Neanderthal, based on the skull found at Teshik-Tash. Source: V.A. Ranov: DA 185 (1993).

identified five archaeological levels, the faunal record is dominated by Siberian ibex and also includes red deer, wild horse, brown bear etc. The lithic inventory includes discoid cores and typical Mousterian points. The most remarkable discovery was that of a NEANDERTHAL child, eight or nine years of age, found beneath the deposits of the first level. The skeleton was found in a shallow niche on top of which horns of ibex had been set vertically to form a regular circle, suggesting a deliberate burial.

A.P. Okladnikov: ‘Paleolit i mezolit Srednei Azii’,

Srednjaja Azija v epohu kamnja i bronzy ed. V.M. Masson (Moscow and Leningrad, 1966).

PD

Thac Lac culture see COASTAL NEOLITHIC

Thailand see ASIA 3

Thala Borivat see ZHENLA CULTURE

Thapsos Situated on the Magnisi peninsula near Syracuse, this settlement of the later 2nd millennium BC is the type-site of the Sicilian Bronze Age culture that existed in between the CASTELLUCCIO and Pantalica cultural phases, and offers unique evidence of an intrusive trading depot. The original settlement consists of round, oval and rectangular huts, with roofs supported by internal posts. The elaborate grey pottery includes distinctive pedestal vases – some supporting shallow bowl forms – which may have been used as part of eating or drinking rituals.

Soon after 1400 BC the earlier village gained a series of buildings of a quite different style: rectangular structures about 20 m long placed around the four sides of a paved courtyard, with associated paved streets. These unusual structures are usually interpreted as warehouses or as part of a palace/ storage complex, and it is assumed that at this stage Thapsos effectively became a small trading ‘port’. It is not yet agreed whether the builders of the complex were local or intrusive – there is little material culture directly associated with the structure. However, it can only be understood in terms of the complex trading networks that developed in the Mediterranean at this period, evidenced by the Mycenaen and Cypriot ware found in the associated tombs.

The 400 or so rock-cut tombs associated with this settlement were excavated by Paolo Orsi in the 1890s and exhibit carved portals, often approached via a ramp, beyond which are single and multiple

THEORY AND THEORY BUILDING 571

chambers with niches. The tombs contained multiple inhumations, and grave-goods including pottery, paste beads and bronze weaponry.

P. Orsi: ‘Thapsos, necropoli sicula con vasi e bronzi miceni’, Monumenti Antichi vi (1895); G. Voza: ‘Thapsos, primi resultati delle piu recenti ricerche’, Atti XIV Riunione Scientifica Istituto Italiana Preistoria e Protostoria

(Florence, 1972), 175–205.

RJA

Thebes (anc. Waset; modern Luxor) Extensive Egyptian site situated on both sides of the Nile, about 500 km south of Cairo, consisting primarily of temples and tombs dating from at least as early as the 3rd millennium BC until the Roman period. For the archaeological remains on the east bank see

KARNAK and LUXOR; for the west bank see DEIR ELBAHARI, DEIR EL-MEDINA, MALKATA, MEDINET HABU, RAMESSEUM, SAFF-TOMB, VALLEY OF THE

KINGS and VALLEY OF THE QUEENS.

H.E. Winlock: The rise and fall of the Middle Kingdom in Thebes (New York, 1947); E. Riefstahl: Thebes in the time of Amunhotep III (Norman, 1964); L. Manniche: City of the dead: Thebes in Egypt (London, 1987).

IS

theory and theory building At the most fundamental level, abstract thinking about archaeology tries to make explicit the purposes of archaeology and to relate these aims directly to an efficient and defensible archaeological methodology. It may try to link these aims to the place, or function, that archaeologists are deemed to hold within society generally. It may try to analyse how archaeologists select areas of inquiry, and identify and prioritize research goals.

However, while all of this is ‘theoretical archaeology’ in the widest sense of the term, most archaeologists have a much narrower conception of archaeological theory. Despite some radical thinking within the POST-PROCESSUAL movement, in practice, most archaeological theorizing attempts to accomplish one of two interrelated objectives:

1 To explain in a general sense how archaeologists can move from a knowledge of the available data on a subject – e.g. material culture from particular sites, or distributions of sites within a region – to making some useful statement about the past or past behaviours. Archaeological theory is, in this sense, an explicit discussion of the link between data and different levels of interpretation or meaning.

2 To devise, apply or test a conceptual, social or economic model (e.g., FORAGING THEORY) in

572 THEORY AND THEORY BUILDING

relation to a particular aspect of the archaeological record.

Since many of the individual entries in this dictionary discuss the latter, we will concentrate here on the different ways archaeologists have discovered of linking data to meaning. Often the archaeologist gives meaning to primary evidence by making some commonsensical analogy with the way modern humans behave, or by using a clearly argued historical or ETHNOGRAPHIC ANALOGY. Alternatively, the archaeologist might make a wholly imaginative leap or, at the other extreme, attempt to construct a strictly logical argument. Either way, the process by which the statement is made and linked to the data, how it is verified or assessed for plausibility (see also VERIFICATION and FALSIFICATION), and how it is related to existing assumptions and theories about past cultures is of interest to the theorist. Here we can add one further quality of archaeological theorizing: it is the selfconscious statement and analysis of assumptions, accepted principles, rules of procedure and methodologies that have been devised to describe, predict or explain the relationship between archaeological data and social phenomena. To be a theory, rather than simply a way of doing things, an approach to the data/meaning problem must be explicit.

Like other aspects of the discipline, archaeological theory borrows heavily from social and natural sciences. Archaeological theorists have repeatedly turned to leading philosophies of science (e.g. Popper 1934, 1963; Hempel 1965, 1966; Kuhn 1962), and in doing so they have also had to ask whether the nature of archaeological data is different to the nature of data in other areas of human enquiry. Occasionally a philosopher of science has returned the favour (Salmon, 1982). In the philosophy of science, the principal approaches to theory building are often divided into those that build meaning up from looking at individual instances, and those that formulate laws and then deduce hypotheses from them that are testable in the real world – although in practice few research programmes are purely one or the other. These two approaches are discussed in the entry on

INDUCTIVE AND DEDUCTIVE EXPLANATION.

Many of the arguments between those expounding

PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY and POSTPROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY, centre around the

relative truthfulness and usefulness – not quite the same thing – of these different explanatory approaches.

Explicitly or otherwise, and like other scientists,

archaeologists tend to classify different kinds of statement into a sort of hierarchy of interest and (more contentiously) reliability. For example, some archaeological statements such as ‘All large pottery vessels found at site X are decorated with a wave design’ are simple generalizations that can be quite easily proved or disproved (tested) by further research or experiment. These ‘low-level’ theories

–essential to much archaeological description – are usually just summaries of repeated associations which suggest a strongly positive correlation between two sets of data. The link between data and statement is often straightforward – even if at a philosophical level it is contentious to identify correlation with causality. However, although such statements are a building block of archaeology, they rarely add much to our knowledge of the culture at an explanatory level.

The link between data and other kinds of statements is much more complex. For example, ‘All pottery decorated with a wave design was used to hold ritual water’ is much more difficult to prove or disprove. As a statement, it may have been prompted by the archaeologist making a simplistic link between the motif and the area of the site where the pottery was found, or by a statistically significant link noted at a hundred other betterunderstood sites. Either way, the difficulty in the link between the data and the statement is that both the validity and the usefulness of the statement no longer reside in a simple description of correlations between data sets, but depend upon a presumed understanding of an element of human behaviour. We might try to break the statement down into a series of carefully worded definitions linked by logical rules, and test it in various ways. But this would not offer us proof that the statement was true in any general sense. Setting aside the problem of devising convincing tests, and the problem of sampling, those tests would only suggest that the statement was true for as long as the rules about human behaviour, as stated in our argument, obtained. The problem remains when examining any open system

–human behaviour is not the only indefinable variable.

This hints at some of the problems encountered in processual archaeology, and at one of the reasons for the limited success of archaeologists in discovering useful and widely accepted

MIDDLE-RANGE THEORY. This was the name the

New Archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s gave to a concerted attempt to identify and test a body of theories which consistently explained distinctive characteristics of the archaeological record, whatever context they might be applied to. By

developing a platform of verified theories, often linking human behaviour to archaeological evidence, archaeologists would be able to make secure inferences. This emphasis on testing hypotheses against data gave theory building in processual archaeology a strongly POSITIVIST flavour (see for example, IWO ELERU). Michael Schiffer’s

BEHAVIORAL ARCHAEOLOGY also attempted to

build testable laws with regard to the dialogue between human behaviour and the archaeological

record. His C-TRANSFORMS and N-TRANSFORMS

described and codified the cultural and natural processes which formed the archaeological record (Schiffer 1976). Gibbon (1989) provides a thorough examination of the LOGICAL POSITIVIST assumptions underlying the New Archaeology and argues that the movement failed to construct and verify a useful body of theory.

Other theorists, from both CONTEXTUAL

ARCHAEOLOGY and the broad POST-PROCESSUAL

ARCHAEOLOGY, have attacked the processualist approach for a number of reasons. They argue that the kinds of theories that can be stated in such a way as to make them verifiable tend to be extremely simple, mechanistic theories. In other words, the processual archaeologists are doomed only to succeed with the trivial. The interesting questions asked by archaeologists concern social phenomena that cannot be isolated, and are often unique in any particular manifestation. This means that essential elements of the verification obtained by experimentation in the natural sciences, notably the notion of closed systems and repeatability, are absent. They accuse processual archaeologists of dressing up their arguments in scientific language, illustrations and paraphernalia, which far from making arguments explicit and challengable, act to cover up archaeology’s unavoidable platform of assumptions, its obscure and broken sets of data.

Gibbon (1989: 144–80) also describes what he terms the ‘realist’ approach to knowledge gathering, formulated by various philosophers of science since the demise of logical positivism. This approach is much more self-conscious about the effect of preconceptions on theory building, and better adapted to dealing with complex open systems and hidden causes. Logical positivism’s insistence on absolutes

– specifically the equivalence of causality and correlation – meant that it could not offer useful ways of analysing relationships between phenomena in most of the circumstances scientists faced. By contrast, ‘statements of laws in realist science make a claim about the activity of a tendency’, so that rather than attempting to formulate universal truths or laws ‘the task of the applied scientist is to un-

THEORY AND THEORY BUILDING 573

tangle the web of interlocking influences’ in each empirical manifestation.

A related approach to the ways in which theory is actually constructed in archaeology has also been outlined by Ian Hodder (1992: 213–40). This takes as its inspiration a close analysis of what Hodder, as an archaeologist, believes that archaeologists actually do when they approach an archaeological problem. As an example, Hodder describes his process of thought when investigating a particular site, showing how the assumptions and hypotheses he initially held went through a series of radical revision and refinements as excavation progressed. In this process, many of the ideas are not stated formally or closely defined in a strictly logical or ‘scientific’ manner – as they would have been in a more processual approach. Instead, they informed the decisions made on where and how to excavate in a sort of continuous dialectic. Hodder characterizes this as a hermeneutic (interpretative or explanatory) circle. According to this idea, rather than setting out to construct theories with testable propositions to arrive at some objective verified statement, archaeologists should acknowledge that they build most archaeological theories from a whole set of earlier assumptions and theories, some carefully considered and others half baked. The important part of the process is not the theory building, or even the theory testing in any formal sense, but continually setting the theory against the evidence in a particular context. Even as the theory is readjusted, the evidence grows and alters in character and complexity, inviting a continual reworking and re-presentation of the theory – a sort of truthseeking spiral. It is this continual reshifting of knowledge that prevents theory from becoming circular, even though it is to some extent both generated by and tested against the archaeological evidence.

An interesting feature of this argument is that its description of the central motor of theory building – the generation of ideas, their formulation into statements, their setting against the evidence, their repeated revision – is not dissimilar to the actions prescribed in the New Archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s. The difference is that Hodder’s approach focuses on a tightening oscillation around the ‘truth’, rather than a laborious but secure way of validating single statements. And the concern shifts from specifying the exact status and relationships of the components of the theory or model (in an effort to increase the universality of the theory and to tie it securely to other explanatory efforts) to an ongoing pragmatic effort to find a ‘best fit’ model or theory for a particular circumstance.

574 THEORY AND THEORY BUILDING

The rhetoric of the various camps of archaeological theory suggests that their approaches to truth-seeking in archaeology are different in essence, whereas often differences seem to resolve themselves into style and communication. This is important because it suggests that practising archaeologists may legitimately choose between them on the basis of appropriateness and utility – make ‘trade-offs’ – when theory-building in different areas. In some areas, for example when attempting to justify analogies or create law-like generalizations, the usefulness of which can be leveraged by other archaeologists, it may be convenient to practise the truth-seeking methods and rhetoric of processual archaeology. In other circumstances, archaeologists may not want to invest time and effort in building (and expensively and laboriously justifying) a single theory of dubious value, when the alternative is to throw twenty specific but flimsy theories at a rich and evolving set of data knowing that only the fittest will survive.

As implied above, a distinguishing feature of middle-range theory in archaeology is that it not only attempts to build an explicit verified link between data and human action, but also attempts to generalize this link. That is, it attempts to state a defining rule or principle that will hold good beyond the specific cultural or archaeological context in which it was formulated. In this, it is similar to other theory-building approaches such as the attempt to build cross-cultural laws or use

ETHNOGRAPHIC ANALOGIES. The tension between

the formulation of theories about particular human behaviour based on particular evidence, and the formulation of generalizing theories about societies or human behaviour at a wider level, is a strong feature of the development of archaeological theory. In a discipline dependent upon the tenuous link between material culture and human behaviour, and with inherently patchy sets of evidence, the attraction of generalizing theories is undeniable. Whether such theorizing is framed as a law, or a formal or suggestive analogy, is perhaps simply a question of efficiency and clarity (see also

COVERING LAW).

In the wider social sciences, ‘general’ or ‘social’ theory is the name given to the highest-level theories that explain how regularities in human societies are generated. MARXISM, for example, offers a series of statements about human social organization as an explanation for both regularities seen in human societies over time and the behaviour of key phenomena within every society of a certain kind. This kind of general theory is extremely difficult to prove or disprove within the social

sciences, as it inevitably depends upon hypothesized links and relationships that cannot be observed in the real world. Marxism depends ultimately upon a belief in the linking concept of contradictions in the forces of production. Although most high-level theories are less general and less complex in application than Marxism, the large and disparate body of economic and social theory in archaeology includes older concepts such as

DIFFUSIONISM or HYDRAULIC DESPOTISM as well

as relative newcomers such as

and WORLD SYSTEMS THEORY.

Whether a particular general theory is accepted depends upon both plausibility (how well it seems to accord with the available evidence) and receptiveness (i.e. the social and academic environment in which the theory is put forward). Because of this dependence upon receptiveness, some archaeologists have argued that it is wrong to speak about archaeological theory without a self-conscious examination of how archaeology as a discipline, and particular approaches within archaeology, relate to wider concerns and beliefs within modern society. This concern with the social practice of disciplines such as archaeology, often termed praxis (Greek for ‘practice’), is characteristic of post-processual archaeology. Just as David Clarke in 1973 described the loss of innocence of the New Archaeology, as a process whereby implicit thinking was replaced by explicit theory building and testing, so postprocessual theorists came eventually to speak of the ‘innocence’ of thinkers such as Lewis Binford and other processual archaeologists, whose attempts to build bodies of tested theories of archaeology imply a belief in a scientific archaeology free from the wider influences of society. Post-processualists argued that even if such theories can be shown to be ‘true’, in the sense that they have a consistent relationship with the raw archaeological data, they can never be formulated ‘objectively’. The selection of the theory to be tested, its exact formulation, the extent and the way in which it is applied to the evidence, and above all the importance it is accorded will all inevitably be informed by the research PARADIGM and the wider intellectual and social environment of the discipline. Perhaps the classic example of the importance of praxis to theory building in archaeology is GENDER ARCHAEOLOGY. Gender archaeology not only confronts many assumptions within archaeology, but also makes clear that many fundamental questions about human prehistory have simply never been posed: historically, because of the male-centred intellectual and social environment, they were not considered important.