- •Abbreviations

- •1 Overview of Antimicrobial Therapy

- •Factors in Antibiotic Selection

- •Factors in Antibiotic Dosing

- •Microbiology and Susceptibility Testing

- •PK/PD and Other Considerations in Antimicrobial Therapy

- •Antibiotic Failure

- •Pitfalls in Antibiotic Prescribing

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •2 Empiric Therapy Based on Clinical Syndrome

- •Empiric Therapy of CNS Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of HEENT Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of GI Tract Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Genitourinary Tract Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- •Empiric Therapy of Bone and Joint Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

- •Sepsis/Septic Shock

- •Febrile Neutropenia

- •Transplant Infections

- •Toxin-Mediated Infectious Diseases

- •Bioterrorist Agents

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •Gram Stain Characteristics of Isolates

- •Parasites, Fungi, Unusual Organisms in Blood

- •Parasites, Fungi, Unusual Organisms in CSF/Brain

- •Parasites, Fungi, Unusual Organisms in Lungs

- •Parasites, Fungi, Unusual Organisms in Heart

- •Parasites, Fungi, Unusual Organisms in the Liver

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •5 HIV Infection

- •HIV Infection Overview

- •Stages of HIV Infection

- •Acute (Primary) HIV Infection

- •Initial Assessment of HIV Infection

- •Indications for Treatment of HIV Infection

- •Antiretroviral Treatment

- •Treatment of Other Opportunistic Infections in HIV

- •HIV Coinfections (HBV/HCV)

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •6 Prophylaxis and Immunizations

- •Surgical Prophylaxis

- •Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- •Chronic Medical Prophylaxis

- •Endocarditis Prophylaxis

- •Travel Prophylaxis

- •Tetanus Prophylaxis

- •Immunizations

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •Empiric Therapy of CNS Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of HEENT Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Vascular Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Gastrointestinal Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Bone and Joint Infections

- •Empiric Therapy of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

- •Common Pediatric Antimicrobial Drugs

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •8 Chest X-Ray Atlas

- •References and Suggested Readings

- •9 Infectious Disease Differential Diagnosis

- •11 Antimicrobial Drug Summaries

- •Appendix

- •Malaria in Adults (United States)

- •Malaria in Children (United States)

- •Index

Chapter 5. HIV Infection |

301 |

Chapter 5 |

|

HIV Infection |

|

Paul E. Sax, MD |

|

Jean E. Hage, MD |

|

Arthur Gran, MD |

|

Jeffrey Baron, PharmD |

|

HIV Infection Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

.302. . . . . . . . . |

Stages of HIV Infection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

303 |

Acute (Primary) HIV Infection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

304. . . . . . . . . . |

Approach to HIV Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

305. |

Initial Assessment of HIV Infection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

308. . . . . . . . . . |

Indications for Treatment of HIV Infection .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. |

312 |

Antiretroviral Treatment .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. |

313 |

Antiretroviral Treatment Failure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

316 |

Prophylaxis of Opportunistic Infections in HIV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

319. . . . . . . . . |

Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

323. . . . . . . . . |

Treatment of Other Opportunistic Infections in HIV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

338 |

HIV Coinfections (HBV/HCV) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

344 |

References and Suggested Readings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

351 |

For HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

365. . |

For HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

366 |

302 |

A n t i b i o t i c E s s e n t i a l s |

HIV INFECTION OVERVIEW

Paul E. Sax, M.D.

Infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) leads to a chronic and without treatment usually fatal infection characterized by progressive immunodeficiency, a long clinical latency period, and opportunistic infections.. The hallmark of HIV disease is infection and viral replication within T-lymphocytes expressing the CD4 antigen (helper-inducer lymphocytes), a critical component of normal cell-mediated immunity.. Qualitative defects in CD4 responsiveness and progressive depletion in CD4 cell counts increase the risk for opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia, and neoplasms such as lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.. HIV infection can also disrupt blood monocyte, tissue macrophage, and B-lymphocyte (humoral immunity) function, predisposing to infection with encapsulated bacteria.. Direct attack of CD4-positive cells in the central and peripheral nervous system can cause HIV meningitis, peripheral neuropathy, and dementia.. More than 1 million people in the United States and 30 million people worldwide are infected with HIV.. Without treatment, the average time from acquisition of HIV to an AIDS-defining opportunistic infection is about 10 years; survival then averages 1–2 years.. There is tremendous individual variability in these time intervals, with some patients progressing from acute HIV infection to death within 1–2 years, and others not manifesting HIV-related immunosuppression for > 20 years after HIV acquisition.. Antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis against opportunistic infections have markedly improved the overall prognosis of HIV disease. . The approach to HIV infection is shown in Figure 5..1..

HIV INFECTION

Diagnosis and Evaluation |

|

|

Treatment |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

History, physical, labs (p. 308) HIV antibody testing (p. 305)

CD4 T-cell count (p. 309) Plasma HIV RNA (p. 307)

|

Antiretroviral |

|

|

Opportunistic |

|

||

|

therapy |

|

|

infections |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initiation (p. 312) |

Prophylaxis (p. 320) |

|||||

Optimal regimen (p. 316) |

Treatment (p. 323) |

||||||

Drug failure (p. 316) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5.1. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of HIV Infection

Chapter 5. HIV Infection |

303 |

STAGES OF HIV INFECTION

A.Viral Transmission. HIV infection is acquired primarily by sexual intercourse (anal, vaginal, infrequently oral), exposure to contaminated blood (primarily needle transmission), or maternal-fetus (perinatal) transmission.. Sexual practices with the highest risk of transmission include unprotected receptive anal intercourse (especially with mucosal tearing), unprotected receptive vaginal intercourse (especially during menses), and unprotected rectal/vaginal intercourse in the presence of genital ulcers (e..g.., primary syphilis, genital herpes, chancroid).. Lower risk sexual practices include insertive anal/vaginal intercourse and oral-genital contact.. The risk of transmission after a single encounter with an HIV source has been estimated to be 1 in 150 with needle sharing, 1 in 300 with occupational percutaneous exposure, 1 in 300–1000 with receptive anal intercourse, 1 in 500–1250 with receptive vaginal intercourse, 1 in 1000–3000 with insertive vaginal intercourse, and 1 in 3000 with insertive anal intercourse.. Transmission risk increases with the number of encounters and with higher HIV RNA plasma levels.. The mode of transmission does not affect the natural history of HIV disease..

B.Acute (Primary) HIV Infection (p. 304). Acute HIV occurs 1–4 weeks after transmission,

and is accompanied by a burst of viral replication with a decline in CD4 cell count. . Most patients manifest a symptomatic mononucleosis-like syndrome, which is often overlooked.. Acute HIV infection is confirmed by a high HIV RNA in the absence of HIV antibody..

C. Seroconversion. Development of a positive HIV antibody test usually occurs within 4 weeks of acute infection, and invariably (with few exceptions) by 6 months..

D.Asymptomatic HIV Infection lasts a variable amount of time (average 8–10 years), and

is accompanied by a gradual decline in CD4 cell counts and a relatively stable HIV RNA level (sometimes referred to as the viral “set point”)..

E.Symptomatic HIV Infection. Previously referred to as “AIDS Related Complex (ARC),” findings include thrush or vaginal candidiasis (persistent, frequent, or poorly responsive to treatment), cervical dysplasia/carcinoma in-situ, herpes zoster (recurrent episodes or involving multiple dermatomes), oral hairy leukoplakia, peripheral neuropathy, diarrhea, or constitutional symptoms (e..g.., low-grade fevers, weight loss)..

F.AIDS is defined by a CD4 cell count < 200/mm3, a CD4 cell percentage of total lymphocytes <14%, or one of several AIDS-related opportunistic infections. . Common opportunistic infections include Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia, cryptococcal meningitis, recurrent bacterial pneumonia, Candida esophagitis, CNS toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. . Other AIDS indicators in HIV-infected patients include candidiasis of the bronchi, trachea, or lungs; disseminated/extrapulmonary coccidiomycosis, cryptococcosis, or histoplasmosis; chronic (>1 month) intestinal cryptosporidiosis or isosporiasis; Kaposi’s sarcoma; lymphoid interstitial pneumonia/pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia; disseminated/extrapulmonary Mycobacterium (avium-intracellulare, kansasii,

304 |

A n t i b i o t i c E s s e n t i a l s |

other species) infection; progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML); recurrent Salmonella septicemia; or HIV wasting syndrome..

G.Advanced HIV Disease is diagnosed when the CD4 cell count is < 50/mm3.. Most AIDS-related deaths occur at this point. . Common late stage opportunistic infections are caused by CMV disease (retinitis, colitis) or disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI)..

ACUTE (PRIMARY) HIV INFECTION

A.Description. Acute clinical illness associated with primary acquisition of HIV, occurring 1–4 weeks after viral transmission (range: 6 days to 6 weeks). . Symptoms develop in 50–90%, but are often mistaken for the flu, mononucleosis, or other nonspecific viral syndrome. . More severe symptoms may correlate with a higher viral set point and more rapid HIV disease progression. . Even without therapy, most patients recover, reflecting development of a partially effective immune response and depletion of susceptible CD4 cells..

B.Differential Diagnosis includes EBV, CMV, viral hepatitis, enteroviral infection, 2° syphilis, toxoplasmosis, HSV with erythema multiforme, drug reaction, Behcet’s disease, acute lupus..

C.Signs and Symptoms usually reflect hematogenous dissemination of virus to lymphoreticular and neurologic sites:

• Fever (97%)..

• Pharyngitis (73%).. Typically non-exudative (unlike EBV, which is usually exudative)..

• Rash (77%).. Maculopapular viral exanthem of the face and trunk is most common, but can involve the extremities, palms and soles..

• Arthralgia/myalgia (58%)..

• Neurologic symptoms (12%). . Headache is most common. . Neuropathy, Bell’s palsy, and meningoencephalitis are rare, but may predict worse outcome..

• Oral/genital ulcerations, thrush, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss..

D.Laboratory Findings

1. CBC. Lymphopenia followed by lymphocytosis (common). . Atypical lymphocytosis is variable, but usually low level (unlike EBV, where atypical lymphocytosis may be 20–30% or higher).. Thrombocytopenia occurs in some..

2.Elevated transaminases in some but not all patients..

3.Depressed CD4 cell count. Can rarely be low enough to induce opportunistic infections..

4.HIV antibody. Usually negative, although persons with prolonged symptoms of acute HIV may have positive antibody tests if diagnosed late during the course of illness..

Chapter 5. HIV Infection |

305 |

E.Confirming the Diagnosis of Acute HIV Infection

1.Obtain HIV antibody after informed consent (if required by state law) to exclude prior disease..

2.Order viral load test (HIV RNA PCR), preferably RT-PCR. . HIV RNA confirms acute HIV infection prior to seroconversion. . Most individuals will have very high HIV RNA

(>100,000 copies/mL). . Be suspicious of a false-positive test if the HIV RNA is low (< 20,000 copies/mL).. For any positive test, it is important to repeat HIV RNA and HIV antibody testing. . p24 antigen can also be used to establish the diagnosis, but is less sensitive than HIV RNA PCR..

3.Order other tests/serologies if HIV RNA test is negative. Order throat cultures for bacterial/viral respiratory pathogens, EBV VCA IgM/IgG, CMV IgM/IgG, HHV-6 IgM/IgG, and hepatitis serologies as appropriate to establish a diagnosis for patient’s symptoms..

F.Management of Acute HIV Infection

1.Initiate antiretroviral therapy. The rationale behind this change is to treat a greater proportion of people with HIV, regardless of disease stage, is based on accumulating evidence of the benefits of earlier initiation of HIV treatment and, conversely, the potential for uncontrolled viral replication and CD4 depletion..

2.Obtain HIV resistance genotype (see p. . 317) because of a rising background prevalence of transmission of antiretroviral therapy-resistant virus.. A genotype resistance test is preferred; therapy can be st arted pending results of the test..

3.Possible benefits for treatment of acute HIV infection. Possible (but unproven) benefits include hastening symptom resolution, reducing viral transmission, lowering virologic “set point,” and preserving virus-specific CD4 responses..

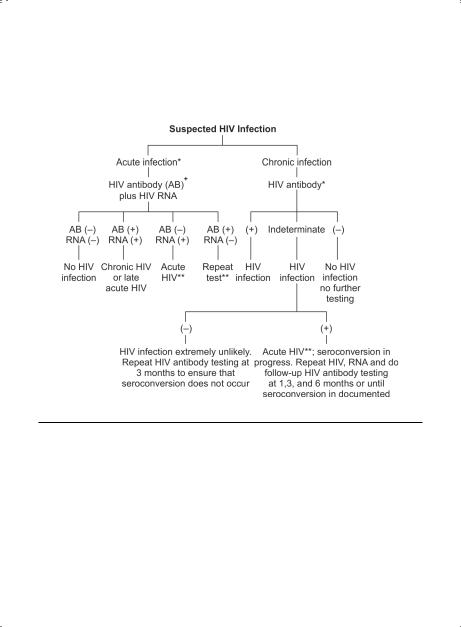

APPROACH TO HIV TESTING (Figure 5.2)

A.Standard HIV Antibody Tests. Most patients produce antibody to HIV within 6–8 weeks of exposure; half will have a positive antibody test in 3–4 weeks, and nearly 100% will have detectable antibody by 6 months..

1.ELISA. Usual screening test.. All positives must be confirmed with Western blot or other more specific tests..

2.Western blot. CDC criteria for interpretation: positive: at least two of the following bands: p24, gp41, gp160/120; negative: no bands; indeterminate: any HIV band, but does not meet criteria for positivity..

3.Test performance. Standard method is ELISA screen with Western blot confirmation..

a.ELISA negative: Western blot is not required (ELISA sensitivity 99. .7%, specificity 98..5%).. Obtain HIV RNA if acute HIV infection is suspected..

b.. ELISA positive: Confirm with Western blot.. Probability that ELISA and Western blot are both false-positives is extremely low (< 1 per 140,000).. Absence of p31 band could be a clue to a false positive Western blot..

c. Unexpected ELISA/Western blot: Repeat test to exclude clerical/computer error..

306 |

A n t i b i o t i c E s s e n t i a l s |

4.Indeterminate Western Blot. Common clinical problem, affecting 4–20% of reactive ELISAs.. Usually due to a single p24 band or weak other bands.. Causes include seroconversion in progress, advanced HIV disease with loss of antibody response,

Figure 5.2. Approach to HIV Testing

(–) = negative test; (+) = positive test..

*Occurs 1–4 weeks after viral transmission.. Most patients manifest a viral syndrome (fever, pharyngitis ± rash/ arthralgias), which is often mistaken for the flu and therefore overlooked..

**HIV RNA in acute HIV infection should be very high (usually > 100,000 copies/mL)..

+All positive ELISA tests must be confirmed by Western Blot; usually this is done automatically in clinical laboratories..

++ May be long-term non-progressor or laboratory error..

Chapter 5. HIV Infection |

307 |

cross-reacting antibody from pregnancy, blood transfusions, organ transplantation, autoantibodies from collagen vascular disease, infection with HIV-2, influenza vaccination, or recipient of HIV vaccine. . In low-risk patients, an indeterminate result almost never represents true HIV infection. . Since seroconversion in progress is generally associated with high HIV RNA levels, the recommended approach is to order an HIV RNA test..

B.Quantitative Plasma HIV RNA (HIV Viral Load Assays)

1.Description. Measures amount of HIV RNA in plasma.. High sensitivity of assays allows detection of virus in most patients not on antiviral therapy.. Used to diagnose acute HIV infection and more commonly to monitor the response to antiretroviral therapy..

2.Uses of HIV RNA Assay

a.Confirms diagnosis of acute HIV infection. A high HIV RNA with a negative HIV antibody test confirms acute HIV infection prior to seroconversion..

b.Helpful in initial evaluation of HIV infection. Establishes baseline HIV RNA and

helps (along with CD4 cell count) determine whether to initiate or defer therapy, as HIV RNA correlates with rate of CD4 decline..

c.Monitors response to antiviral therapy. HIV RNA changes rapidly decline 2–4 weeks after starting or changing effective antiretroviral therapy, with slower decline thereafter. . Patients with the greatest HIV RNA response have the best clinical outcome.. No change in HIV RNA suggests therapy will be ineffective..

d.Estimates risk for opportunistic infection. For patients with similar CD4 cell counts, the risk of opportunistic infections is higher with higher HIV RNAs..

3.Assays and Interpretation

a.Tests, sensitivities, and dynamic range. Three main assays, each with advantages and disadvantages, are widely used.. Any assay can be used to diagnose acute HIV infection and guide/monitor therapy, but the same test should be used to follow patients longitudinally..

1.RT-PCR Amplicor (Roche): Sensitivity = 400 copies/mL; dynamic range = 400–750,000 copies/mL..

2.RT-PCR Ultrasensitive 1.5 (Roche): Sensitivity = 50 copies/mL; dynamic range = 50–75,000 copies/mL..

3.bDNA Versant 3.0 (Bayer): Sensitivity = 75 copies/mL; dynamic range = 50– 500,000 copies/mL..

b.Correlation between HIV RNA and CD4. HIV RNA assays correlate inversely with CD4 cell counts, but do so imperfectly (e..g.., some patients with high CD4 counts have relatively high HIV RNA levels, and vice versa..) For any given CD4, higher HIV RNA levels correlate with more rapid CD4 decline.. In response to antiretroviral therapy, changes in HIV RNA generally precede changes in CD4 cell count..