Varian Microeconomics Workout

.pdf

doubling both prices have on the set of commodity bundles that Abishag

can a®ord? |

|

. |

(c)Suppose that Abishag decides to sell 10 quinces. Label her ¯nal consumption bundle in your graph with the letter C.

(d)Now, after she has sold 10 quinces and owns the bundle labeled C, suppose that the price of kumquats falls so that kumquats cost the same as quinces. On the diagram above, draw Abishag's new budget line, using red ink.

(e)If Abishag obeys the weak axiom of revealed preference, then there are some points on her red budget line that we can be sure Abishag will not choose. On the graph, make a squiggly line over the portion of Abishag's red budget line that we can be sure she will not choose.

9.2 (0) Mario has a small garden where he raises eggplant and tomatoes. He consumes some of these vegetables, and he sells some in the market. Eggplants and tomatoes are perfect complements for Mario, since the only recipes he knows use them together in a 1:1 ratio. One week his garden yielded 30 pounds of eggplant and 10 pounds of tomatoes. At that time the price of each vegetable was $5 per pound.

(a) What is the monetary value of Mario's endowment of vegetables?

.

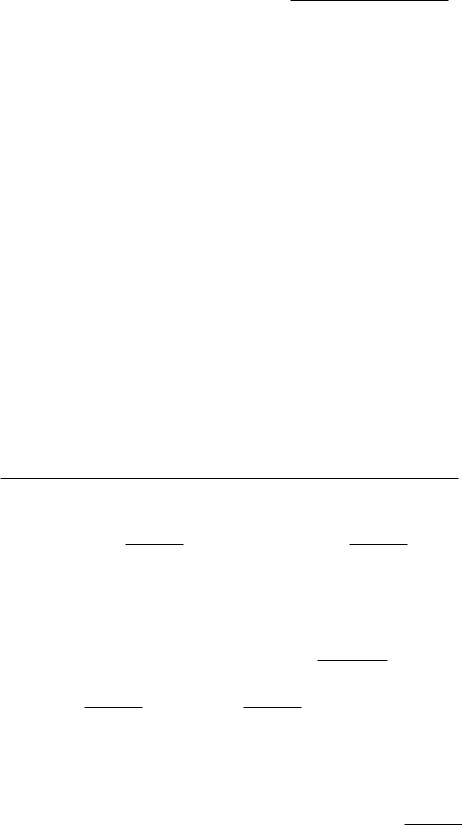

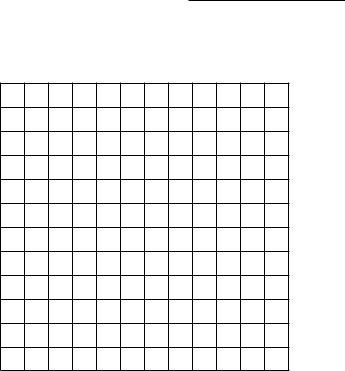

(b) On the graph below, use blue ink to draw Mario's budget line. Mario

ends up consuming pounds of tomatoes and pounds of eggplant. Draw the indi®erence curve through the consumption bundle that Mario chooses and label this bundle A.

(c) Suppose that before Mario makes any trades, the price of tomatoes rises to $15 a pound, while the price of eggplant stays at $5 a pound.

What is the value of Mario's endowment now? Draw his new budget line, using red ink. He will now choose a consumption bundle

consisting of tomatoes and eggplants.

(d) Suppose that Mario had sold his entire crop at the market for a total of $200, intending to buy back some tomatoes and eggplant for his own consumption. Before he had a chance to buy anything back, the price of tomatoes rose to $15, while the price of eggplant stayed at $5. Draw his

budget line, using pencil or black ink. Mario will now consume

pounds of tomatoes and |

|

pounds of eggplant. |

(e) Assuming that the price of tomatoes rose to $15 from $5 before Mario made any transactions, the change in the demand for tomatoes due to the

substitution e®ect was |

|

|

The change in the demand for tomatoes |

|||||||

due to the ordinary income e®ect was |

|

The change in the |

||||||||

|

||||||||||

demand for tomatoes due to the endowment income e®ect was |

|

|

||||||||

|

The total change in the demand for tomatoes was |

|

|

. |

||||||

|

Eggplant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

30

20

10

0 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

|

|

|

Tomatoes |

|

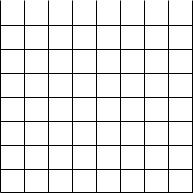

9.3 (0) Lucetta consumes only two goods, A and B. Her only source of income is gifts of these commodities from her many admirers. She doesn't always get these goods in the proportions in which she wants to consume them, but she can always buy or sell A at the price pA = 1 and B at the price pB = 2. Lucetta's utility function is U(a; b) = ab, where a is the amount of A she consumes and b is the amount of B she consumes.

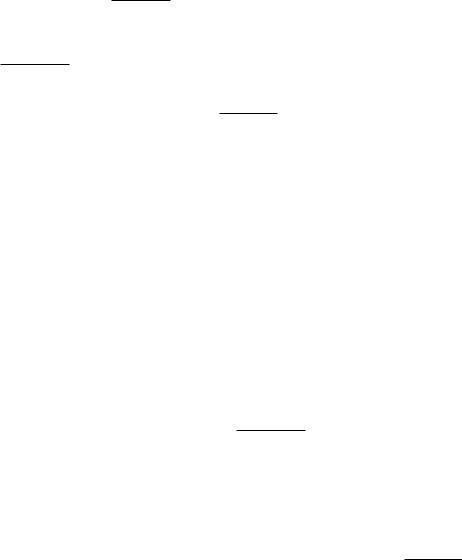

(a) Suppose that Lucetta's admirers give her 100 units of A and 200 units of B. In the graph below, use red ink to draw her budget line. Label her initial endowment E.

(b) What are Lucetta's gross demands for A? |

|

And for B? |

||

|

||||

|

|

|

|

. |

(c) What are Lucetta's net demands? |

|

|

. |

|

(d) Suppose that before Lucetta has made any trades, the price of good B falls to 1, and the price of good A stays at 1. Draw Lucetta's budget line at these prices on your graph, using blue ink.

(e) Does Lucetta's consumption of good B rise or fall? |

|

By |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

how much? |

|

|

|

What happens to Lucetta's consumption of |

|||||||||||

good A? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

|

Good B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

600 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

400 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

300 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

0 |

|

75 |

150 |

225 |

300 |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Good A |

|

|

|||

(f) Suppose that before the price of good B fell, Lucetta had exchanged all of her gifts for money, planning to use the money to buy her consumption

bundle later. How much of good B will she choose to consume?

How much of good A? |

|

. |

(g) Explain why her consumption is di®erent depending on whether she

was holding goods or money at the time of the price change.

.

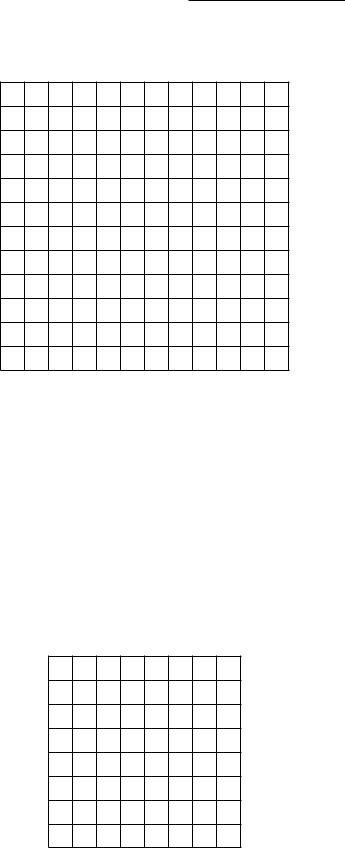

9.4 (0) Priscilla ¯nds it optimal not to engage in trade at the going prices and just consumes her endowment. Priscilla has no kinks in her indi®erence curves, and she is endowed with positive amounts of both goods. Use pencil or black ink to draw a budget line and an indi®erence curve for Priscilla that would be consistent with these facts. Suppose that the price

of good 2 stays the same, but the price of good 1 falls. Use blue ink to show her new budget line. Priscilla satis¯es the weak axiom of revealed preference. Could it happen that Priscilla will consume less of good 1 than be-

fore? Explain.

.

9.5 (0) Potatoes are a Gi®en good for Paddy, who has a small potato farm. The price of potatoes fell, but Paddy increased his potato consumption. At ¯rst this astonished the village economist, who thought that a decrease in the price of a Gi®en good was supposed to reduce demand. But then he remembered that Paddy was a net supplier of potatoes. With the help of a graph, he was able to explain Paddy's behavior. In the axes below, show how this could have happened. Put \potatoes" on the horizontal axis and \all other goods" on the vertical axis. Label the old equilibrium A and the new equilibrium B. Draw a point C so that the Slutsky substitution e®ect is the movement from A to C and the Slutsky income e®ect is the movement from C to B. On this same graph, you are also going to have to show that potatoes are a Gi®en good. To do this, draw a budget line showing the e®ect of a fall in the price of potatoes if Paddy didn't own any potatoes, and only had money income. Label the new consumption point under these circumstances by D. (Warning: You probably will need to make a few dry runs on some scratch paper to get the whole story straight.)

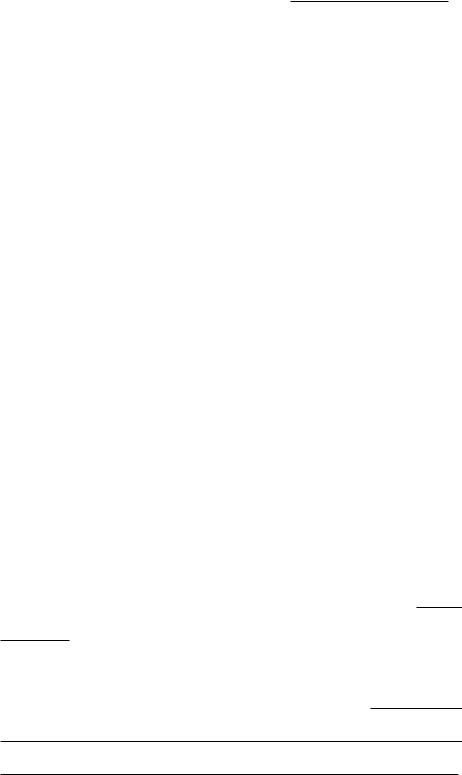

9.6 (0) Recall the travails of Agatha, from the previous chapter. She had to travel 1,500 miles from Istanbul to Paris. She had only $200 with which to buy ¯rst-class and second-class tickets on the Orient Express when the price of ¯rst-class tickets was $.20 a mile and the price of second-class tickets was $.10 a mile. She bought tickets that enabled her to travel all the way to Paris, with as many miles of ¯rst class as she could a®ord. After she boarded the train, she discovered to her amazement that the price of second-class tickets had fallen to $.05 a mile while the price of ¯rst-class tickets remained at $.20 a mile. She also discovered that on the train it was possible to buy or sell ¯rst-class tickets for $.20 a mile and to buy or sell second-class tickets for $.05 a mile. Agatha had no money left to buy either kind of ticket, but she did have the tickets that she had already bought.

(a) On the graph below, use pencil to show the combinations of tickets that she could a®ord at the old prices. Use blue ink to show the combinations of tickets that would take her exactly 1,500 miles. Mark the point that she chooses with the letter A.

First-class miles

1600

1200

800

400

0400 800 1200 1600

Second-class miles

(b)Use red ink to draw a line showing all of the combinations of ¯rst-class and second-class travel that she can a®ord when she is on the train, by trading her endowment of tickets at the new prices that apply on board the train.

(c)On your graph, show the point that she chooses after ¯nding out about the price change. Does she choose more, less, or the same amount

of second-class tickets? |

|

. |

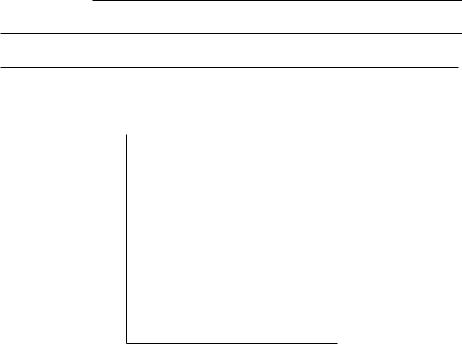

9.7 (0) Mr. Cog works in a machine factory. He can work as many hours per day as he wishes at a wage rate of w. Let C be the number of dollars he spends on consumer goods and let R be the number of hours of leisure that he chooses.

(a) Mr. Cog earns $8 an hour and has 18 hours per day to devote to labor or leisure, and he has $16 of nonlabor income per day. Write an

equation for his budget between consumption and leisure.

Use blue ink to draw his budget line in the graph below. His initial endowment is the point where he does no work and enjoys 18 hours of leisure per day. Mark this point on the graph below with the letter A. (Remember that although Cog can choose to work and thereby \sell" some of his endowment of leisure, he cannot \buy leisure" by paying somebody else to loaf for him.) If Mr. Cog has the utility function U(R; C) = CR,

how many hours of leisure per day will he choose? |

|

How many |

||

hours per day will he work? |

|

|

. |

|

Consumption

240

200

160

120

80

40

0 |

4 |

8 |

12 |

16 |

20 |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leisure |

(b) Suppose that Mr. Cog's wage rate rises to $12 an hour. Use red ink to draw his new budget line. (He still has $16 a day in nonlabor income.) If he continued to work exactly as many hours as he did before the wage increase, how much more money would he have each day to spend on

consumption? |

|

|

But with his new budget line, he chooses to |

|||

work |

|

|

hours, and so his consumption increases by |

|

. |

|

(c) Suppose that Mr. Cog still receives $8 an hour but that his nonlabor income rises to $48 per day. Use black ink to draw his budget line. How

many hours does he choose to work? |

|

. |

(d) Suppose that Mr. Cog has a wage of $w per hour, a nonlabor income of $m, and that he has 18 hours a day to divide between labor and leisure. Cog's budget line has the equation C + wR = m + 18w. Using the same methods you used in the chapter on demand functions, ¯nd the amount of leisure that Cog will demand as a function of wages and of nonlabor income. (Hint: Notice that this is the same as ¯nding the demand for R when the price of R is w, the price of C is 1, and income is m+18w.) Mr.

Cog's demand function for leisure is R(w; m) = |

|

|

Mr. Cog's |

|

supply function for labor is therefore 18 ¡ R(w; m) = |

|

|

. |

|

9.8 (0) Fred has just arrived at college and is trying to ¯gure out how to supplement the meager checks that he gets from home. \How can anyone live on $50 a week for spending money?" he asks. But he asks to no avail. \If you want more money, get a job," say his parents. So Fred glumly investigates the possibilities. The amount of leisure time that he has left after allowing for necessary activities like sleeping, brushing teeth, and studying for economics classes is 50 hours a week. He can work as many hours per week at a nearby Taco Bell for $5 an hour. Fred's utility function for leisure and money to spend on consumption is U(C; L) = CL.

(a) Fred has an endowment that consists of $50 of money to spend on

consumption and hours of leisure, some of which he might \sell" for money. The money value of Fred's endowment bundle, including both his money allowance and the market value of his leisure time is therefore

Fred's \budget line" for leisure and consumption is like a budget line for someone who can buy these two goods at a price of $1 per

unit of consumption and a price of per unit of leisure. The only di®erence is that this budget line doesn't run all the way to the horizontal axis.

(b)On the graph below, use black ink to show Fred's budget line. (Hint: Find the combination of leisure and consumption expenditures that he could have if he didn't work at all. Find the combination he would have if he chose to have no leisure at all. What other points are on your graph?) On the same graph, use blue ink to sketch the indi®erence curves that give Fred utility levels of 3,000, 4,500, and 7,500.

(c)If you maximized Fred's utility subject to the above budget, how

much consumption would he choose? (Hint: Remember how to solve for the demand function of someone with a Cobb-Douglas utility function?)

(d) The amount of leisure that Fred will choose to consume is

hours. This means that his optimal labor supply will be |

|

hours. |

Consumption

300

250

200

150

100

50

0 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leisure |

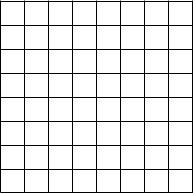

9.9 (0) George Johnson earns $5 per hour in his job as a tru²e sniffer. After allowing time for all of the activities necessary for bodily upkeep, George has 80 hours per week to allocate between leisure and labor. Sketch the budget constraints for George resulting from the following government programs.

(a) There is no government subsidy or taxation of labor income. (Use blue ink on the graph below.)

Consumption

400

300

200

100

0 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

|

|

|

|

Leisure |

(b)All individuals receive a lump sum payment of $100 per week from the government. There is no tax on the ¯rst $100 per week of labor income. But all labor income above $100 per week is subject to a 50% income tax. (Use red ink on the graph above.)

(c)If an individual is not working, he receives a payment of $100. If he works he does not receive the $100, and all wages are subject to a 50% income tax. (Use blue ink on the graph below.)

Consumption

400

300

200

100

0 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

|

|

|

|

Leisure |

(d)The same conditions as in Part (c) apply, except that the ¯rst 20 hours of labor are exempt from the tax. (Use red ink on the graph above.)

(e)All wages are taxed at 50%, but as an incentive to encourage work, the government gives a payment of $100 to anyone who works more than 20 hours a week. (Use blue ink on the graph below.)