Учебники / Textbook and Color Atlas of Salivary Gland Pathology - DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT Carlson 2008

.pdf

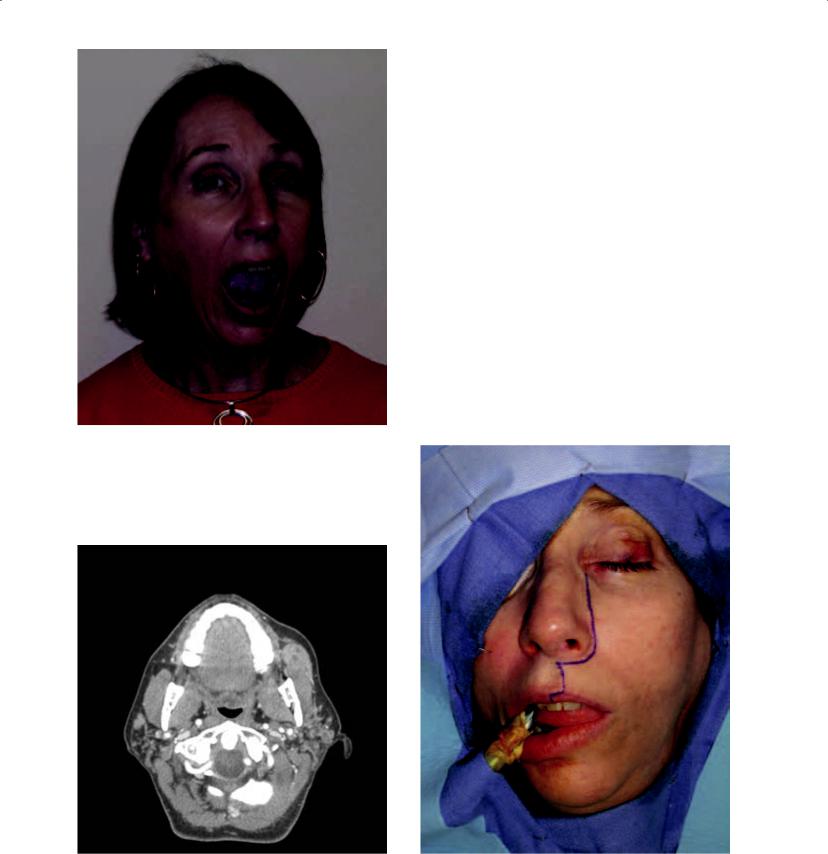

Figure 6.5b. Computerized tomograms identified a heterogenous mass of the left buccal region, associated with minor salivary gland tissue vs. an accessory parotid gland. A salivary gland neoplasm was favored based on clinical and radiographic information.

Figure 6.5a. A 55-year-old woman with a 10-year history of a progressively enlarging mass of the left cheek that is able to be visualized inferior to her left zygomatic buttress when she opens her mouth. She reported a history of Sjogren’s syndrome.

Figure 6.5c. Excision was accomplished with a WeberFerguson incision so as to provide access and minimize trauma to Stenson’s duct and the buccal branch of the facial nerve.

136

Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands |

137 |

d  e

e

Figures 6.5d and 6.5e. An incision in the buccal mucosa (d) was also utilized, which permitted effective dissection of the tissue bed (e).

f |

g |

Figures 6.5f and 6.5g. The specimen was able to be removed without difficulty (f) and was diagnosed as a lymphoepithelial lesion.

DIAGNOSIS OF SJOGREN’S SYNDROME WITH SALIVARY GLAND BIOPSY

Incisional biopsy of minor salivary glands was introduced as a clinical diagnostic procedure for Sjogren’s syndrome in 1966. Many studies since

that time have examined the value of this biopsy procedure (Marx, Hartman, and Rethman 1988). One study graded inflammation in labial salivary gland biopsy specimens from patients with various rheumatologic diseases and in postmortem specimens (Chisolm and Mason 1968). A grading

138 Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands

scheme of lymphocytes and plasma cells per 4 mm2 was established and has been described by numerous authors since its original description (Greenspan et al. 1974). Grade 0 referred to the absence of these cells, grade 1 showed a slight infiltrate, grade 2 showed a moderate infiltrate or less than one focus per 4 mm2, grade 3 showed one focus per 4 mm2, and grade 4 showed more than one focus per 4 mm2. It has been noted that grade 4 (more than one focus of 50 or more lymphocytes per 4 mm2 area of gland) is seen only in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and was not seen in postmortem specimens. Due to the strong association with the presence of Sjogren’s syndrome, focal sialadenitis in a labial minor salivary gland incisional biopsy specimen with a focus score of more than one focus/4 mm2 has been proposed as the diagnostic criterion for the salivary component of this disease (Daniels, Silverman, and Michalski et al. 1975). It has been pointed out that the focus score cannot separate early from late disease as chronicity of symptoms and focus score did not show a relationship (Greenspan et al. 1974). The highest focus score, however, was seen in patients with the sicca components of Sjogren’s syndrome without associated connective tissue disease. Finally, since variation of disease apparently exists from minor salivary gland lobe to lobe, at least 4–7 lobes of minor salivary gland tissue should be removed and examined microscopically (Greenspan et al. 1974).

Incisional biopsy of the parotid gland has at least theoretical benefit and justification in the diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Previous recommendations for major salivary gland biopsy reported potential complications of facial nerve damage, cutaneous fistula, and scarring of the facial skin when utilizing a parotid biopsy to establish or confirm a diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Incisional parotid biopsy may be performed without assuming any of these complications, except in very rare circumstances (Marx, Hartman, and Rethman 1988). Recent studies, in fact, point to a higher yield of diagnosis when using the parotid biopsy (Marx 1995) (Figure 6.6). In Marx’s series of 54 patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, 31 (58%) had a positive labial biopsy, while 54 (100%) had a positive parotid biopsy (Marx 1995). He concluded his study by stating that incisional parotid biopsy will confirm and definitively document the diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome (Figure 6.7). The incisional parotid biopsy will also serve to rule out

the presence of lymphoma, which is observed to develop in approximately 5–10% of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome (Daniels 1991; Talal and Bunim 1964). Patients with Sjogren’s syndrome are felt to have 47 times greater incidence of lymphoma than that of an age-controlled population (Marx, Hartman, and Rethman 1988). Ten such lymphomas were reported in Marx’s study. They developed 4–12 years after the diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome was made, with a mean of 7.2 years. In 8 of the 10 cases, a rapid change in the size of the parotid enlargement was noted, and all of the patients exhibited a darkening of the skin overlying the enlarged parotid gland. These changes dictated biopsy of the parotid gland in the background of the systemic disease, with the knowledge that lymphoma does not develop in the lower lip in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome.

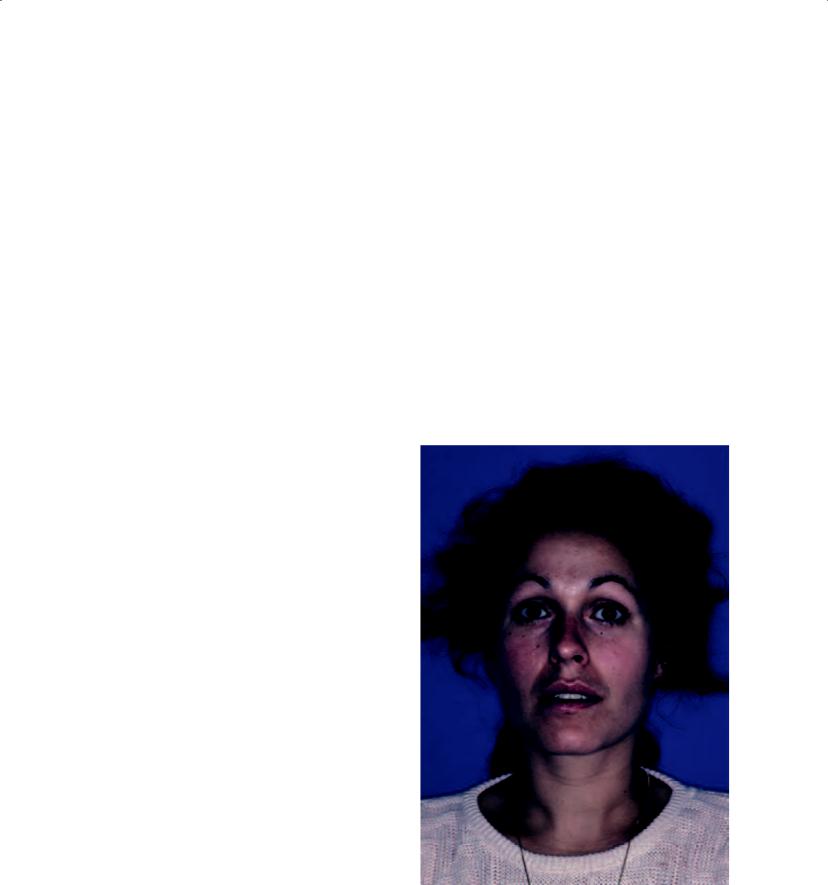

Figure 6.6a. A 32-year-old woman with the recent development of dry eyes and mouth, possibly suggestive of Sjogren’s syndrome.

b |

c |

|

Figures 6.6b and 6.6c. No swelling of the parotid glands was appreciated on physical examination. An incisional biopsy |

|

of the lower lip and right parotid gland were performed. The histopathology showed a normal lower lip biopsy (b) and signs |

|

consistent with Sjogren’s syndrome on parotid biopsy (c). |

Figure 6.7a. An incisional parotid biopsy was performed on the patient seen in Figure 6.1. The incision is placed behind the right ear, which enables the surgeon to procure sufficient parotid tissue to establish a diagnosis, while also providing a cosmetic scar.

Figure 6.7b. The dissection proceeds through skin and subcutaneous tissue, after which time the parotid capsule is noted. This is incised and a 1 cm2 specimen of parotid gland is removed. The closure requires a reapproximation of the parotid capsule so as to avoid a salivary fistula postoperatively.

139

140 Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands

Histopathology of Sjogren’s Syndrome

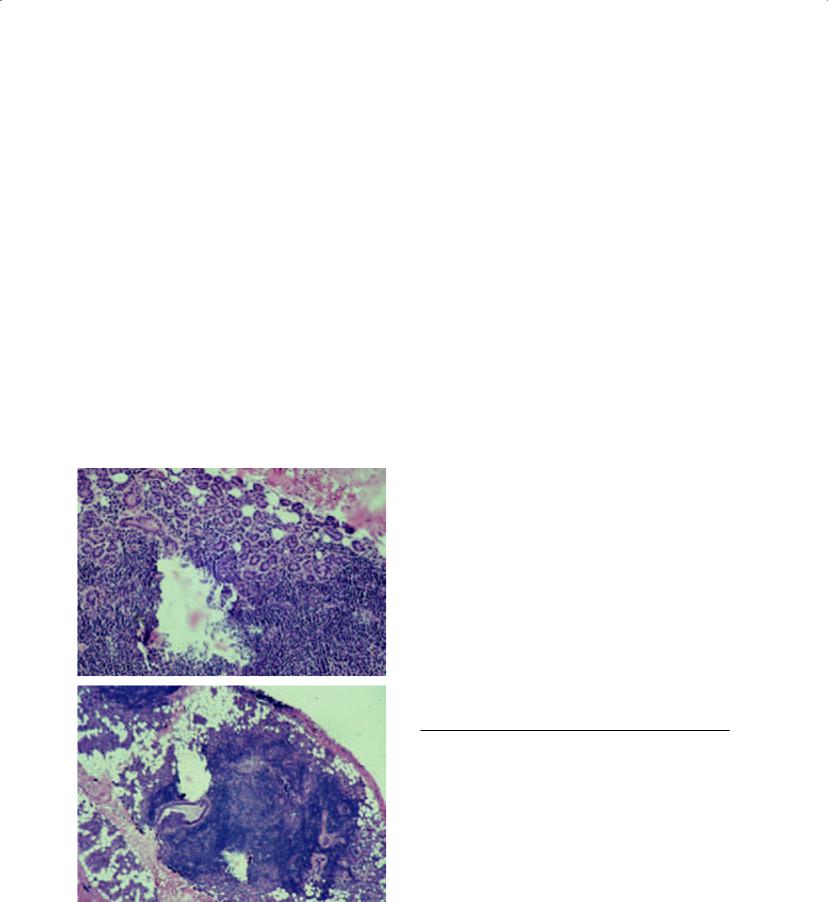

Abnormal salivary gland function is associated with well-defined histologic alterations including clustering of lymphocytic infiltrates as a common feature of all salivary glands and other organs affected by Sjogren’s syndrome (Figure 6.8). Histologic evaluation of enlarged parotid or submandibular glands usually reveals the benign lymphoepithelial lesion, with a lymphocytic infiltrate and epimyoepithelial islands. These features are not invariably noted in the major salivary glands, however (Daniels 1991). The characteristic microscopic feature of Sjogren’s syndrome in the minor glands is a focal lymphocytic infiltrate, and includes focal aggregates of 50 or more lymphocytes, defined as a focus, that are adjacent to normal appearing acini and the consistent presence of these foci in all or most of the glands in the specimen (Daniels 1991). Epimyoepithelial islands occur uncommonly in minor glands of patients affected by Sjogren’s syndrome.

a

b

Figures 6.8a and 6.8b. The histopathology of the incisional parotid biopsy of the patient in Figure 6.1. Signs consistent with Sjogren’s syndrome were noted.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a chronic systemic disease characterized by the production of non-caseating granulomas whose etiology is unknown. It can affect any organ system, thereby mimicking rheumatic diseases causing fever, arthritis, uveitis, myositis, and rash (Table 6.2). The peripheral blood shows a dichotomy of depressed cellular immunity and enhanced humoral immunity. Depressed cellular immunity is manifested by lymphopenia and cutaneous energy. The enhanced humoral immunity is noted by polyclonal gammopathy and autoantibody production.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis occurs most commonly in American blacks and northern European Caucasians. It is eight times more common in American blacks than American Caucasians (Hellmann 1993). Women are affected slightly more frequently than men. Patients with sarcoidosis generally present with one of the following four problems: respiratory symptoms such as dry cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain (40–50%); constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and malaise (25%); extrathoracic inflammation such as peripheral lymphadenopathy (25%); and rheumatic symptoms such as arthritis (5–10%) (Hellmann 1993).

Respiratory symptoms are the most common presenting chief complaints including those previously mentioned. Regardless of symptoms, greater than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis have an

Table 6.2. Clinical involvement by sarcoidosis.

Clinical Finding |

Frequency |

Differential Diagnosis |

|

in |

|

|

Sarcoidosis |

|

|

(%) |

|

|

|

|

Arthritis |

5–10 |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Parotid gland |

5 |

Sjogren’s syndrome |

enlargement |

|

|

Upper airway |

3 |

Wegener’s |

disease |

|

granulomatosis |

Uveitis |

22 |

Spondyloarthropathies |

Facial nerve palsy |

2 |

Lyme disease |

Keratoconjunctivitis |

5 |

Sjogren’s syndrome |

|

|

|

abnormal chest radiograph. Four types of radiographic appearance have been described: type 0 is normal; type I shows enlargement of hilar, mediastinal, and occasionally paratracheal lymph nodes; and type II shows the adenopathy seen in type I as well as pulmonary infiltrates (Figure 6.9). Type III demonstrates the infiltrates without the adenopathy. Type II involvement is the most common among patients with sarcoidosis who have respiratory distress.

Two patterns of arthritis are observed in sarcoidosis, and are classified as to whether the arthritis occurs within the first 6 months after the onset of the disease, or late in the course of the disease. The early form of arthritis often begins in the ankles and may spread to involve the knees and other joints. The axial skeleton is typically spared. Monarthritis in the early phase is unusual.

Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands |

141 |

Erythema nodosum, a syndrome of inflammatory cutaneous nodules frequently found on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, occurs in about two-thirds of patients and is strikingly associated with early arthritis. Lofgren’s syndrome involves a triad of hilar lymphadenopathy, erythema nodosum, and arthritis. The late form of arthritis occurs at least 6 months after the onset of sarcoidosis, and is generally less dramatic than the early form. The knees are the most common joints to be involved, followed by the ankles. Monarthritis can occur in the late form of arthritis, and erythema nodosum is not commonly noted.

Other rheumatic manifestations associated with sarcoidosis include involvement of the larynx, nasal turbinates, and nasal cartilage, thereby resembling the clinical presentation of Wegener’s granulomatosis (Figure 6.10). Eye involvement

Figures 6.9a and 6.9b. |

Posterior- |

|

anterior (a) and lateral |

(b) chest |

|

radiographs of a patient with type II |

|

|

sarcoidosis. This patient presented |

|

|

with severe shortness of breath. |

a |

|

b

Figure 6.10. Severe nasal cartilage involvement by sarcoidosis in this elderly woman. (Image courtesy of Dr. James Sciubba.)

Figures 6.9a and 6.9b. Continued

Figure 6.11. Bilateral parotid enlargement in a 50-year-old black woman (left > right) with a known history of sarcoidosis. (Image courtesy of Dr. James Sciubba.)

142

Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands |

143 |

a |

b |

|

Figures 6.12a, 6.12b, and 6.12c. A 55-year-old man with |

|

bilateral submandibular gland swellings (a and b), as well as |

|

lower lip lesions (c). Excision of the left submandibular gland |

|

and biopsy of the lower lip swelling identified non-caseating |

|

granulomas. Additional workup identified signs consistent with |

c |

sarcoidosis. |

occurs in 22% of patients, with uveitis being most common (Hellmann 1993). The triad of anterior uveitis in conjunction with parotitis and facial nerve palsy has been referred to as Heerfordt’s syndrome, also known as uveoparotid fever.

While salivary gland involvement seems to primarily involve the parotid gland (Figure 6.11),

the submandibular gland can also be involved (Vairaktaris, Vassiliou, and Yapijakis et al. 2005; Werning 1991). The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology registry identified 85 cases of sarcoidosis. In the 77 cases in which a gland was specified, parotid involvement occurred in 65% of the cases, while the submandibular gland accounted

144 Systemic Diseases Affecting the Salivary Glands

for 13% of cases (Werning 1991). Submandibular gland enlargement may occur in the absence of parotid swelling, with or without clinical evidence of minor salivary gland involvement (Figure 6.12). Minor salivary gland involvement is occasionally noted histologically in the presence of clinically apparent major salivary gland swelling (Mandel and Kaynar 1994). In fact, enlargement of the major salivary glands may be the first identifiable sign of sarcoidosis (Fatahzadeh and Rinaggio 2006). When this occurs, therefore, it is important to differentiate the parotid swelling associated with sarcoidosis from that of Sjogren’s syndrome (Folwaczny et al. 2002). Salivary gland biopsy with histopathologic examination is one means to make this distinction.

DIAGNOSIS OF SARCOIDOSIS WITH SALIVARY GLAND BIOPSY

As with Sjogren’s syndrome diagnoses with salivary gland biopsies, early stage disease is perhaps more readily diagnosed with a parotid biopsy rather than a minor salivary gland biopsy. It has been pointed out that cases of sarcoidosis that do not clinically produce parotid enlargement nonetheless show involvement at the microscopic level (Marx 1995). In this review, the labial biopsy was positive in 38% of cases while 88% of parotid biopsies were positive for sarcoidosis. The lesions of sarcoidosis in labial salivary gland biopsies tend to be sparse such that multiple labial glands require excision for microscopic analysis. Another report investigated the yield of minor salivary gland biopsy in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Nessan and Jacoway 1979). In this study of 75 patients, noncaseating granulomas were present in minor salivary gland biopsies in 44 patients (58%). There was no correlation with minor salivary gland biopsy yield and stage of the disease. The highest yield for diagnosis of sarcoidosis was found in transbronchial lung biopsies (93%). Nonetheless, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is one of exclusion, owing to an absence of a diagnostic gold standard. As such, a compatible clinical picture is established based on the patient’s symptoms, physical, and radiographic findings. The biopsy of salivary gland tissue or other tissue identifies the presence of non-caseating granulomas such that a provisional diagnosis of sarcoidosis is made. It then becomes necessary to exclude other sources of granulomatous inflammation, such as Crohn’s

Figure 6.13. Histopathology of sarcoidosis. (Image courtesy of Dr. Joseph A. Regezi.)

disease, deep fungal infections, and others. It is important to point out that there are no pathognomonic diagnostic tests for sarcoidosis. Rather, the salivary biopsy must be considered with an elevated angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and lysozyme result, and an altered ratio of CD4/CD8 cells, among others, so as to offer a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Kasamatsu et al. 2007).

Histopathology of Sarcoidosis

Numerous granulomas may be seen in the salivary gland biopsy. The typical sarcoid granuloma is non-caseating and consists of a tightly packed central focus of histiocytes that is surrounded by lymphocytes and fibroblasts at its periphery (Figure 6.13). The histiocytes may be epithelioid and may join to form multinucleated giant cells, frequently of the Langhans type.

Sialosis

Sialosis, also known as sialadenosis, represents a bilateral enlargement of the parotid gland that is multifactorial in its etiology (Table 6.3). It is not commonly associated with an autoimmune phenomenon, as is the case for Sjogren’s syndrome and sarcoidosis, although it can easily be confused with these two pathologic processes due to its clinical presentation (Figure 6.14). Quite commonly, sialosis is caused by nutritional disturbances such as alcoholism, bulimia, or in the rare case of achalasia (Figure 6.15). Chronic alcoholism with or without

Table 6.3. Classification of sialosis.

Malnutritional sialosis

Achalasia

Bulemia

Alcoholism

Hormonal sialosis

Sex hormonal sialosis

Diabetic sialosis

Thyroid sialosis

Pituitary and adrenocortical disorders

Neurohumoral sialosis

Peripheral neurohumoral sialosis

Central neurogenous sialosis

Dysenzymatic sialosis

Hepatogenic sialosis

Pancreatogenic (exocrine) sialosis

Nephrogenic sialosis

Dysproteinemic sialosis

Mucoviscidosis

Drug-induced sialosis

From Werning 1991.

Figure 6.14. A 32-year-old man with a chronic history of bilateral parotid swellings. He gave a history of achalasia. The history suggested that the parotid swellings were consistent with a diagnosis of sialosis. There were no physical or historical findings suggestive of another diagnosis.

Figure 6.15. The fluoroscopic images of the barium swallow performed in the patient in Figure 6.14. The characteristic “bird’s beak” deformity is noted, reflective of failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax. This is diagnostic of achalasia.

145