Учебники / Textbook and Color Atlas of Salivary Gland Pathology - DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT Carlson 2008

.pdf

116 Sialolithiasis

gland stones and are intimately associated with the mandible. Phleboliths are commonly multiple in number and also exist within the neck outside of the submandibular triangle. They are scattered and have a classic lamellated appearance with a lucent core. Finally, phleboliths are smaller than sialoliths and demonstrate an oval shape, compared to the sialolith, whose elliptical shape has been created by a salivary duct (Mandel and Surattanont 2004). One further entity worthy of mention is calcified atheromas of the carotid artery, which is sufficiently distant from the submandibular triangle so as to not be confused with a submandibular sialolith. These are most commonly located inferior and posterior to the mandibular angle adjacent to the intervertebral space between cervical vertebrae 3 and 4 (Friedlander and Freymiller 2003).

While the diagnosis of sialolithiasis is frequently confirmed radiographically, it is important for the clinician to not obtain radiographs prior to performing a physical examination. Bimanual palpation of the floor of the mouth may reveal evidence of a stone in a large number of patients. Similar palpation of the gland may also permit detection of a stone as well as the degree of fibrosis present within the gland. Examining the opening of Wharton’s duct for the flow of saliva or pus is an important aspect of the evaluation. It has been estimated that approximately one-quarter of symptomatic submandibular glands that harbor stones are non-functional or hypofunctional. Radiographs should be obtained and may reveal the presence of a stone. It has been reported that 80% of submandibular stones are radio-opaque, 40% of parotid stones are radio-opaque, and 20% of sublingual gland stones are radio-opaque (Miloro 1998).

Treatment of Sialolithiasis

General principles of management of patients with sialolithiasis include conservative measures such as effective hydration, the use of heat, gland massage, and sialogogues that might result in flushing a small stone out of the duct. A course of oral antibiotics may also be beneficial. These measures may be particularly appropriate since some patients may carry a clinical diagnosis of sialadenitis in case of a radiolucent sialolith. As such, the treatment is the same in the initial management of both diagnoses.

SUBMANDIBULAR SIALOLITHIASIS

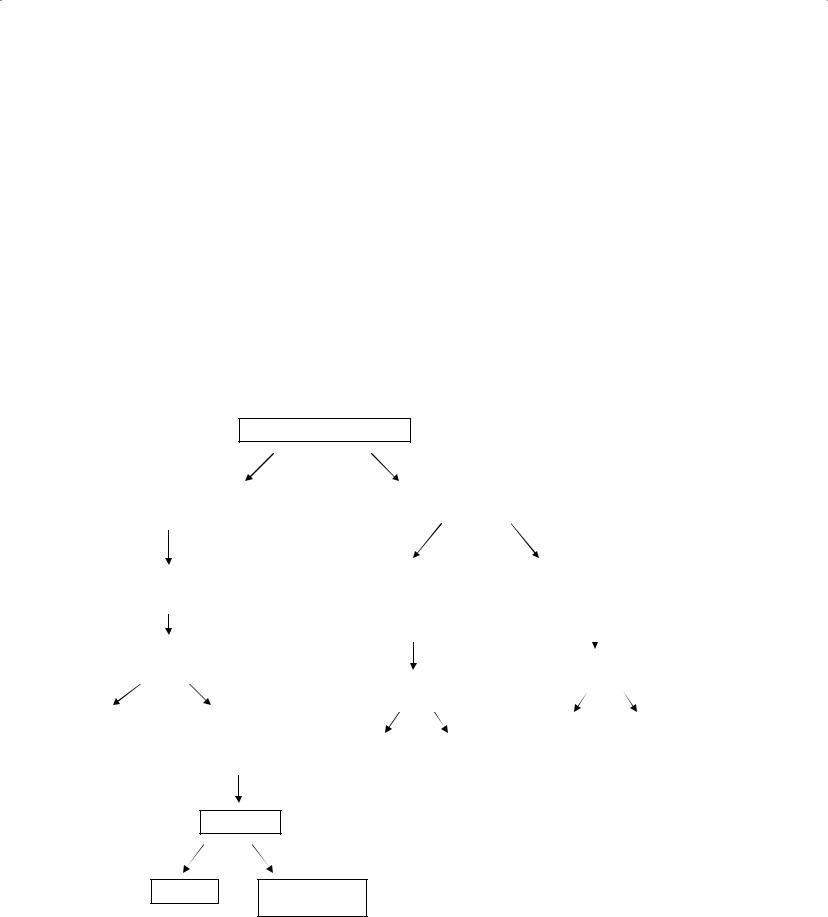

The treatment of salivary calculi of the submandibular gland is a function of the location and size of the sialolith (Figure 5.10). For example, sialoliths present within the duct may often be retrieved with a transoral sialolithotomy procedure and sialodochoplasty. In general terms, if the stone can be palpated transorally, it can probably be removed transorally. A review of 172 patients who underwent intraoral sialolithotomy of a submandibular stone assessed results as to complete removal, partial removal, and failure (Park, Sohn, and Kim 2006). The effect of location, size, presence of infection, and palpability of the calculi on the results was assessed. Univariate analysis showed that palpability and the presence of infection were statistically significant factors affecting transoral sialolithotomy. Palpability was the only significant factor after multivariate analysis. This study provides scientific evidence supporting intraoral removal of extraglandular submandibular gland stones regardless of location, size, presence of infection, or recurrence of calculi as long as the calculi are palpable. This procedure involves excising Wharton’s duct overlying the stone, thereby permitting its retrieval (Figure 5.11). Reconstruction of the duct in the form of a sialodochoplasty permits shortening of the duct and enlargement of salivary outflow, thereby preventing recurrence and allowing for healing of the gland (Rontal and Rontal 1987). A properly performed sialodochoplasty ensures effective flow of saliva from the gland in hopes of maintaining the health of the salivary gland. This procedure involves suturing the edges of the duct’s mucosa to the surrounding oral mucosa (Figure 5.11). The number of sutures placed is arbitrary; however, a sufficient number of sutures is required so as to stabilize the reconstructed duct to the floor of the mouth. Proper postoperative hydration of the patient with free flowing saliva maintains patency of the sialodochoplasty, thereby enhancing the potential for reversal or stabilization of the underlying sialadenitis. Chronic submandibular obstructive sialolithiasis clearly leads to chronic sialadenitis with presumed parenchymal destruction. After removal of the sialolith, however, the apparent resiliency of the submandibular gland usually results in no adverse symptoms (Baurmash 2004). As such, the ability to effectively retrieve a sialolith usually refutes the need to also remove the affected salivary gland.

Sialolithiasis 117

Submandibular sialolithiasis

Location

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intraglandular duct |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extraglandular duct |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hilum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

> 7 mm |

|

|

|

< 7 mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transoral sialolithotomy with sialodochoplasty |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider sialoendoscopy with sialolithotomy, |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

possible papillotomy |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lithotripsy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

Consider |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

lithotripsy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

No |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

Monitor |

|

|

Submandibular gland |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

excision |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor |

|

Consider |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sialoendoscopy |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

Monitor |

|

|

|

Submandibular |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with sialolithotomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

gland excision |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

possible papillotomy |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor |

|

|

Submandibular gland excision |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5.10. Algorithm for submandibular sialolithiasis.

Sialoliths located within the submandibular gland or its hilum are most commonly managed with submandibular gland excision (Figure 5.12). This controversial statement is made based on the relative difficulty to retrieve stones from this anatomic region of the gland, rather than based on the assumption that proximal stones cause permanent structural damage to the gland that results in the need for removal of the gland. To this end, a study examined a series of 55 consecutive patients who underwent transoral removal of stones from the hilum of the submandibular gland (McGurk, Makdissi, and Brown 2004). Stones were able to be retrieved in 54 patients (98%), but four glands

(8%) required subsequent removal due to recurrent obstruction. The authors emphasized that it was necessary for the stone to be palpable and no limitation of oral opening should exist in order for patients to undergo their technique. They reported an acceptable incidence of complications associated with their technique, although they lamented that it remained to be seen if the asymptomatic nature of their patients would be maintained over time.

Shock wave lithotripsy has been reported as a primary form of treatment for submandibular salivary gland stones. Salivary stone lithotripsy requires a gland to be functional by virtue of production of

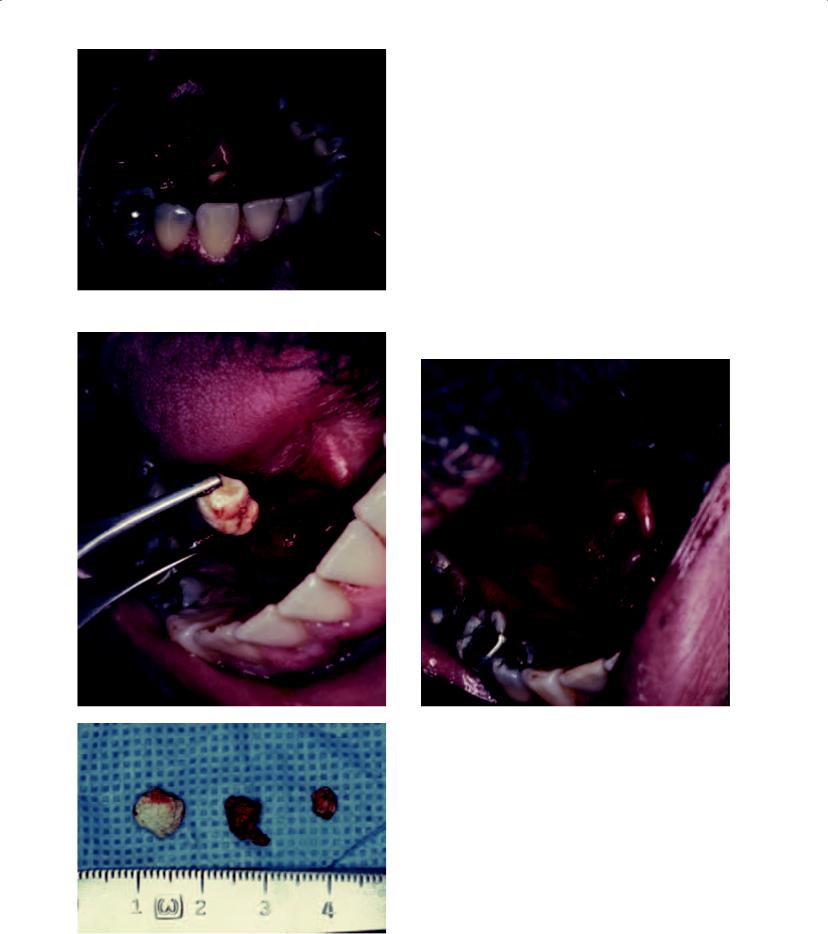

Figure 5.11a. A sialolith is noted at the opening of the right Wharton’s duct. Since this stone was able to be palpated on oral examination, it was removed transorally without necessitating the removal of the right submandibular gland. Reprinted from: Berry, RL. Sialadenitis and sialolithiasis. Diagnosis and management. In: The Comprehensive Management of Salivary Gland Pathology, Carlson ER (ed), Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 407–503.

b |

d |

|

Figures 5.11b, 5.11c, and 5.11d. The main stone was |

|

removed (b), after which time exploration of the proximal |

|

duct revealed two additional stones that were also removed |

|

(c). A sialodochoplasty was performed to widen and shorten |

|

the right Wharton’s duct (d). A sialodochoplasty performed |

|

near the papilla of Wharton’s duct is termed a “papillotomy.” |

|

Reprinted from: Berry, RL. Sialadenitis and sialolithiasis. |

|

Diagnosis and management. In: The Comprehensive Man- |

|

agement of Salivary Gland Pathology, Carlson ER (ed), |

|

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, WB |

c |

Saunders, Philadelphia, 407–503. |

118

Figure 5.12a. The clinical appearance of a man with pain and left submandibular swelling.

Figure 5.12b. His panoramic radiographic shows a sialolith in the left submandibular gland.

Figure 5.12c. A standard transcutaneous approach was followed to submandibular gland excision.

Figure 5.12d. A subfascial dissection of the gland was performed. Inferior retraction on the gland allowed for preservation of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve.

119

120 Sialolithiasis

Figure 5.12e. Superior and anterior retraction of the gland allowed for identification of the sialolith that was located at the hilum of the gland.

f

g

Figures 5.12f and 5.12g. The excised gland (f) was bisected (g) and demonstrated significant scar tissue formation.

saliva in order for the stone fragments to be eliminated from the duct. Some authors have implemented a sour gum test prior to performing extracorporeal lithotripsy (Williams 1999). This test involves the patient chewing sour gum while the clinician looks for swelling of the gland. The development of swelling indicates that the gland is functional such that extracorporeal lithotripsy may be attempted. In the absence of swelling, extracorporeal lithotripsy is contraindicated, and the gland is planned for removal. Two techniques of salivary lithotripsy have been developed, including extracorporeal sonographically controlled lithotripsy and intracorporeal endoscopically guided lithotripsy (Escudier 1998). Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy was first used to treat renal stones in the early 1980s. The shockwaves can be generated by electromagnetic, piezoelectric, and electrohydraulic mechanisms and the resultant waves are brought to a focus through acoustic lenses. They then pass through a water-filled cushion to the stone, where stress and cavitation act to fracture the stone. At the sialolith-water interface a compressive wave is propagated through the stone, thereby subjecting it to stress. Cavitation occurs when reflected energy at the sialolith-water interface results in a rebounding tensile or expansion wave that induces bubbles. When these bubbles collapse a jet of water is projected through the bubble onto the stone’s surface. This force is sufficient to pit the stone and break it. Extracorporeal lithotripsy for submandibular gland stones is somewhat less successful than that of parotid stones (Williams 1999). Ottaviani and his group evaluated the results of 52 patients treated with electromagnetic extracorporeal lithotripsy for calculi of the submandibular gland (n = 36 patients) and parotid gland (n = 16 patients). Complete disintegration was achieved in 46.1% of patients, including 15 with submandibular sialolithiasis and 9 with parotid sialolithiasis. Elimination of the stones was confirmed by sonogram. Residual concrements were detected by ultrasound in 30.8% of patients, including 9 with submandibular stones and 7 with parotid stones. Four patients with residual submandibular stones required surgical retrieval. The authors concluded by indicating that if hilar and intraglandular duct stones are smaller than 7 mm in size, they may be successfully treated with lithotripsy (Williams 1999). The surgeon should proceed with submandibular gland excision if this trial of lithotripsy is not successful, or if stones larger than 7 mm are identified.

Sialolithiasis 121

Intracorporeal lithotripsy techniques are now used in which a miniature endoscope is utilized to manipulate the stone under direct vision. In this technique, shockwaves are applied directly to the surface of the stone under endoscopic guidance. The shockwave may be derived from an electrohydraulic source, a pneumoballistic source, or from a laser. Pneumoballistic energy has been shown to produce calculus fragmentation with greater efficiency than lasertripsy (Arzoz et al. 1996). The disadvantage of these techniques is that the size of the endoscope and probe requires that the duct be incised so as to facilitate entry.

Finally, interventional sialoendoscopy has been developed that may permit the use of a fine

c

d

a

sialoendoscope to retrieve salivary stones (Nakayama, Yuasa, and Beppu et al. 2003) (Figure 5.13). The size of some sialoliths, however, is such that an incision of the papilla may be necessary for their delivery. Interventional sialoendoscopy may be used with lithotripsy to fragment large

b |

e |

Figures 5.13a and 5.13b. Interventional sialoendoscopic instrumentation for retrieval of salivary calculus, including the operating sheaths (a) that accept the miniature endoscope (Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Inc., Culver City, California) in the telescope channel (b).

Figures 5.13c, 5.13d, and 5.13e. The grasping forceps (c), are placed within the working channel of the operating sheaths (d), and are able to retrieve stones that may be identifi ed on diagnostic sialoendoscopy (e). Figure 5.13e courtesy of Dr. Maria Troulis, Boston, Massachusetts.

122 Sialolithiasis

stones so as to achieve a completely non-invasive therapeutic sialoendoscopy.

McGurk, Escudier, and Brown (2004) assessed the efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, basket retrieval as part of interventional sialoendoscopy, and intraoral surgical removal of salivary calculi. Three hundred twenty three patients with submandibular calculi were managed. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy was successful in 43 of 131 (32.8%) patients, basket retrieval was successful in 80 of 109 (73.4%) patients, and surgical removal was successful in 137 of 143 (95.8%) patients with submandibular stones.

PAROTID SIALOLITHIASIS

Sialoliths of the parotid gland are divided anatomically into those that are located within the intrag-

Parotid sialolithiasis

Location

landular duct and the extraglandular duct (Figure 5.14). Extraglandular duct sialoliths may be removed surgically through an intraoral approach (Figure 5.15). In this procedure, a C-shaped incision is made anterior to Stenson’s papilla. Dissection is performed deep (lateral) to the duct such that it is included in the mucosal flap so that the duct is separated from the more lateral soft tissues. A retraction suture may be placed at the anterior aspect of the mucosal aspect of the flap. The duct is dissected from anterior to posterior so as to identify the stone within the duct. Once the stone is located, the duct is incised longitudinally, thereby allowing for retrieval of the sialolith. The mucosal flap is reapproximated; however, the incision in the duct is not sutured. These longitudinal incisions placed in the duct do not appear to result in the formation of strictures, although transverse

Intraglandular duct |

|

Extraglandular duct |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Consider lithotripsy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transoral |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Sialoendoscopy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sialolithotomy |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With sialolithotomy |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Possible papillotomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

|

|

No |

|

|

|

Resolved? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Monitor |

|

Consider extraoral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor |

|

|

Superficial |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

sialolithotomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

parotidectomy |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor |

|

|

Superficial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Consider sialoendoscopy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

parotidectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolved?

Yes

No

Monitor Superficial

parotidectomy

Figure 5.14. Algorithm for parotid sialolithiasis.

Figure 5.15b. The approach for this transoral sialolithotomy involved a mucosal incision anterior to Stenson’s papilla.

Figure 5.15c. A mucosal flap was developed that included Stenson’s duct such that the dissection occurred lateral to the duct.

Figure 5.15a. Management of an extraglandular parotid duct sialolith. The panoramic radiograph demonstrates a small sialolith in the right Stenson’s duct.

d

e

Figures 5.15d and 5.15e. Continued dissection allowed for palpation of the sialolith within the duct. The duct was longitudinally incised over the sialolith (d), such that the stone was able to be removed (e).

123

124 Sialolithiasis

Figure 5.15f. The mucosal fl ap was sutured without reapproximating the incision in Stenson’s duct.

Figure 5.15g. Patent salivary flow was re-established as noted 2 months postoperatively. No further treatment of the gland was required.

incisions in the duct may result in stricture formation (Berry 1995; Seward 1968). Strictures in the parotid duct will respond favorably to intermittent dilation; however, submandibular duct strictures usually require surgical intervention.

Parotid sialoliths located within the intraglandular portion of the ductal system may be addressed through an extraoral approach. Two options exist, one involving a traditional parotidectomy approach (without performing a parotidectomy) with a curvilinear skin incision in the preauricular and upper neck regions (Berry 1995), and the other involving a horizontal incision over the duct in the cheek region (Baurmash and Dechiara 1991). In the former approach, the skin flap is elevated superficial to the parotid fascia, and the duct is identified at the point where it exits the anterior border of the gland. The placement of a lacrimal probe within Stenson’s duct may permit accurate identification of the duct. Once the duct is located, it is dissected posteriorly into the gland and the stone is identified. A longitudinal incision is made over the duct and the stone is retrieved (Figure 5.16). As in the case of a transoral sialolithotomy, the incision in Stenson’s duct is not closed at the conclusion of the surgery. Sialolithotomy performed with a transcutaneous approach in the cheek may also be accomplished for a diagnosis of parotid sialolithiasis (Figure 5.17).

Extracorporeal lithotripsy seems to be quite effective for the treatment of intraparotid stones. With three outpatient treatments, 50% of patients have been reported to be rendered free of calculus (Williams 1999). Half of the remaining patients may be rendered free of symptoms but having small fragments left in the ductal system. In Ottaviani’s cohort of 16 patients with parotid stones, all were relieved of their symptoms with extracorporeal lithotripsy (Ottaviani, Capaccio, and Campi et al. 1996). Nine of their 16 patients experienced complete disintegration and elimination of stones, and 7 patients showed residual stone fragments that were able to be flushed out spontaneously or with salivation induced by citric acid.

McGurk, Escudier, and Brown (2004) found extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy to be successful in 44 of 90 (48.9%) patients with parotid sialoliths, and basket retrieval was successful in 44 of 57 (77.2%) patients with parotid sialoliths. Interestingly, no patients with parotid stones underwent transoral surgical removal.

Figure 5.16a. Axial CT scan demonstrating a parotid sialolith at the hilum with proximal dilatation of the duct due to obstruction of salivary flow.

Figure 5.17a. A lateral oblique plain film demonstrating two sialoliths of Stenson’s duct.

Figure 5.16b. A parotidectomy approach to stone retrieval was performed without parotidectomy.

Figure 5.17b. An incision through skin was placed in a resting tension line of the cheek.

125