- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Introduction

- •2. Evaluation of the Craniomaxillofacial Deformity Patient

- •3. Craniofacial Deformities: Review of Etiologies, Distribution, and Their Classification

- •4. Etiology of Skeletal Malocclusion

- •5. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Traumatic Defects

- •6. Etiology, Distribution, and Classification of Craniomaxillofacial Deformities: Review of Nasal Deformities

- •7. Review of Benign Tumors of the Maxillofacial Region and Considerations for Bone Invasion

- •8. Oral Malignancies: Etiology, Distribution, and Basic Treatment Considerations

- •9. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Infections: Etiologies, Distributions, and Associated Defects

- •11. Craniomaxillofacial Bone Healing, Biomechanics, and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •12. Metal for Craniomaxillofacial Internal Fixation Implants and Its Physiological Implications

- •13. Bioresorbable Materials for Bone Fixation: Review of Biological Concepts and Mechanical Aspects

- •14. Advanced Bone Healing Concepts in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery

- •15. The ITI Dental Implant System

- •16. Localized Ridge Augmentation Using Guided Bone Regeneration in Deficient Implant Sites

- •17. The ITI Dental Implant System in Maxillofacial Applications

- •18. Maxillary Sinus Grafting and Osseointegration Surgery

- •19. Computerized Tomography and Its Use for Craniomaxillofacial Dental Implantology

- •20B. Atlas of Cases

- •21A. Prosthodontic Considerations in Dental Implant Restoration

- •21B. Overdenture Case Reports

- •22. AO/ASIF Mandibular Hardware

- •23. Aesthetic Considerations in Reconstructive and Corrective Craniomaxillofacial Bone Surgery

- •24. Considerations for Reconstruction of the Head and Neck Oncologic Patient

- •25. Autogenous Bone Grafts in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

- •26. Current Practice and Future Trends in Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Microvascular Bone Surgery

- •27. Considerations in the Fixation of Bone Grafts for the Reconstruction of Mandibular Continuity Defects

- •28. Indications and Technical Considerations of Different Fibula Grafts

- •29. Soft Tissue Flaps for Coverage of Craniomaxillofacial Osseous Continuity Defects with or Without Bone Graft and Rigid Fixation

- •30. Mandibular Condyle Reconstruction with Free Costochondral Grafting

- •31. Microsurgical Reconstruction of Large Defects of the Maxilla, Midface, and Cranial Base

- •32. Condylar Prosthesis for the Replacement of the Mandibular Condyle

- •33. Problems Related to Mandibular Condylar Prosthesis

- •34. Reconstruction of Defects of the Mandibular Angle

- •35. Mandibular Body Reconstruction

- •36. Marginal Mandibulectomy

- •37. Reconstruction of Extensive Anterior Defects of the Mandible

- •38. Radiation Therapy and Considerations for Internal Fixation Devices

- •39. Management of Posttraumatic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

- •40. Bilateral Maxillary Defects: THORP Plate Reconstruction with Removable Prosthesis

- •41. AO/ASIF Craniofacial Fixation System Hardware

- •43. Orbital Reconstruction

- •44. Nasal Reconstruction Using Bone Grafts and Rigid Internal Fixation

- •46. Orthognathic Examination

- •47. Considerations in Planning for Bimaxillary Surgery and the Implications of Rigid Internal Fixation

- •48. Reconstruction of Cleft Lip and Palate Osseous Defects and Deformities

- •49. Maxillary Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •50. Mandibular Osteotomies and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •51. Genioplasty Techniques and Considerations for Rigid Internal Fixation

- •52. Long-Term Stability of Maxillary and Mandibular Osteotomies with Rigid Internal Fixation

- •53. Le Fort II and Le Fort III Osteotomies for Midface Reconstruction and Considerations for Internal Fixation

- •54. Craniofacial Deformities: Introduction and Principles of Management

- •55. The Effects of Plate and Screw Fixation on the Growing Craniofacial Skeleton

- •56. Calvarial Bone Graft Harvesting Techniques: Considerations for Their Use with Rigid Fixation Techniques in the Craniomaxillofacial Region

- •57. Crouzon Syndrome: Basic Dysmorphology and Staging of Reconstruction

- •58. Hemifacial Microsomia

- •59. Orbital Hypertelorism: Surgical Management

- •60. Surgical Correction of the Apert Craniofacial Deformities

- •Index

46

Orthognathic Examination

Peter Ward-Booth

It has been estimated that 1.2 million patients in the United States1 could benefit from surgical orthodontics. It is important therefore that a patient with this potential problem should have a standard careful and complete examination. Orthognathic surgery is no longer a “one-off” surgical procedure, but routine oral and maxillofacial surgery in which patients reasonably expect a safe predictable outcome.

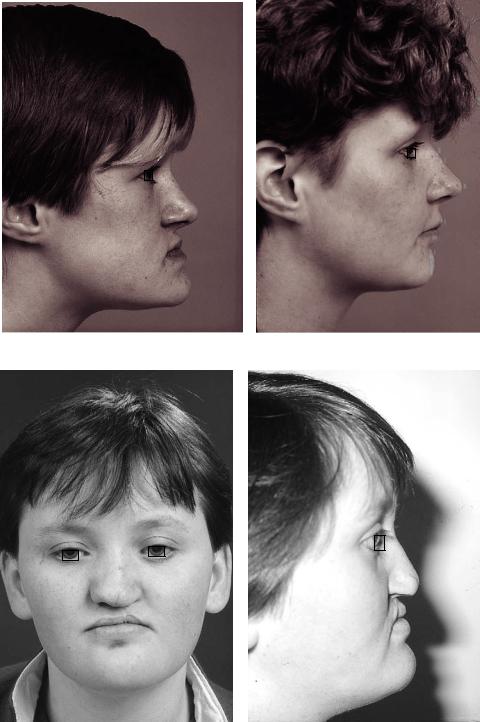

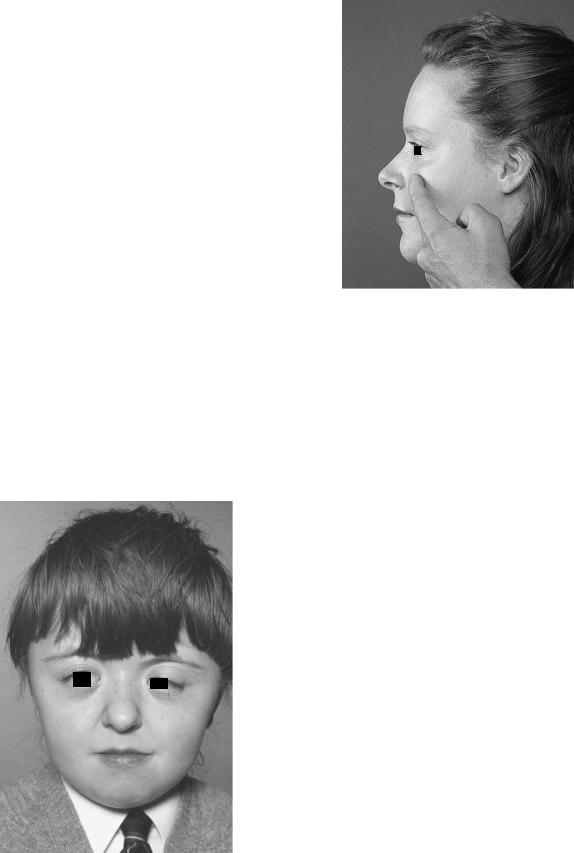

The lifelong functional and aesthetic benefits of orthognathic surgery are enormous in those with severe facial deformity, such as cleft patients, or those less severely afflicted. Poor planning, however, or even worse, failing to discuss orthognathic surgery with the patient, can leave a lifelong legacy of failure (Figures 46.1a–g).

Medical Examination

The medical examination covers two elements. The first concerns the suitability of the patient, both physically and psychologically, to undergo surgery, and the second is a “medical” component of the facial disharmony; for example, a syndromic patient may have associated medical problems. It is however not the role of this chapter to discuss the general medical examination of patients.

Psychologic problems in patients seeking orthognathic surgery are significant. The dysmorphic patient with poor selfesteem and inappropriate body image is unlikely to be happy after orthognathic surgery. These patients do not enter the consultation wearing a large sign warning the surgeon they are dysmorphic personalities. Taking a good history and spending time not only talking to, but more importantly listening to, the patient usually reveals these problems. These dysmorphic patients often seem to have an exaggerated image of what appears to be a minor facial disharmony. They frequently dwell at great length on their problem, which to the surgeon seems minimal. They frequently are introverted with an obsession with the problem, providing on occasion long lists or diagrams of their condition. If surgery proceeds, they expect perfection in the outcome. Frequently they are

older patients and may well have already consulted a number of different specialists about similar cosmetic problems. Such patients must be treated surgically with great caution. Specialist help from interested psychiatrists can be helpful. It should be stressed that if these patients are carefully treated with good support and communications, a satisfied, happy patient is certainly possible. The patient difficult to detect is the dysmorphic patient who actually has a significant facial disharmony.

The available evidence suggests2 that orthognathic patients are different from patients seeking pure cosmetic surgery, such as a face-lift. They do not seem to have the same degree of poor self-esteem, and their response to orthognathic surgery is generally very positive. As in so many aspects of surgery, good information, including realistic comments on the improvements that are possible as well as the complications and postoperative difficulties, yield handsome dividends in patient satisfaction. Unfortunately, a comprehensive explanation of surgery using very vivid language may “put off” some patients who could have coped well with the surgery.

It certainly is a skill to inform a patient fully yet not engender unnecessary anxiety. It is most important that the surgery be explained to close friends or family of the patient, because in the first days after surgery support of the family can be an invaluable aid to the patient. My personal aid to the delicate balance of “informing not frightening” the patient is to arrange for the patient and relatives to sit and talk, on their own, with a patient who has recently had similar surgery. Those patients who have related medical problems, such as acromegalia,3 are important from the surgical point of view because of complications that may arise perioperatively. In some syndromes having a genetic element, genetic counseling should be considered.

Orthognathic surgery is, “normally,” and there is a good case for stating it should be “always,” the second stage of a three-part procedure of orthodontics and surgery. The first stage is orthodontic, the second stage is surgical, and the last stage orthodontic “tidying up.” The examination therefore should be a joint orthodontist/maxillofacial surgeon process.

497

498 |

P. Ward-Booth |

a |

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

c |

|

|

|

|

|

d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

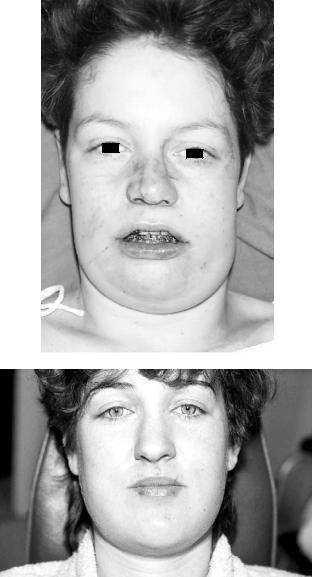

FIGURE 46.1 (a) This patient required a maxillary Le Fort I advancement and bilateral sagittal splint pushback procedure. The acute nasiolabial angle was corrected by inferiorly positioning the maxilla. (b) Postoperative. (c) Cleft patients often display marked

maxillary hypoplasia as the result of poor primary surgery. (d) The full-face view displays this maxillary hypoplasia and highlights the three-dimensional hypoplasia with reduced facial height.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

499 |

|||||

e |

|

|

|

|

|

f |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|

h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

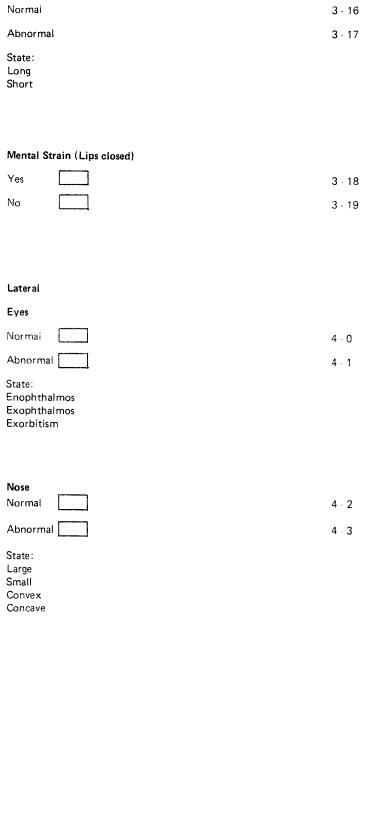

FIGURE 46.1 Continued. (e) Postoperative. (f) Postoperative. (g) Clear evidence of failure of planning; too much attention was focused on the dental element of the face. (h) An unsatisfactory postoperative appearance; the mandibular pushback has highlighted the

prominent nose and nasion. (i) This patient underwent extensive orthodontic treatment, yet the facial appearance was ignored. The result was a good occlusion but unsatisfactory facial appearance.

500

The planning for orthognathic surgery is as much art as science.3 The need for artistic skills, however, can never be used as a reason for “cutting corners,” “guessing,” or a “that’s close enough” type philosophy. The fact that “artistic judgment” is needed for surgery and planning demands even higher and more precise standards of evaluation to provide the data needed to make a treatment decision. The actions of an experienced surgeon when examining or operating can appear to the poorly informed to be intuitive. In reality the experienced surgeon is in fact still working through a careful, wellrehearsed algorithm, but experience allows this to be a faster process. There is no doubt the more precise and meticulous the examination and the surgery, the more artistic the outcome. It is also apparent that while most experienced clinicians agree in broad terms about a diagnosis of an orthognathic case, the plan to the last fraction of a millimeter will vary from clinician to clinician.4 This is as much about cultural, ethnic “norms,” and personal preferences as it is an objective scientific decision.

The Examination Process

The new trainee, faced with the first case to examine, wants a didactic list to work through. Indeed many units provide just that process, and I have outlined my particular process here (Figure 46.2). This however is like a phrase book in a foreign country; you will be able to “get by,” but you will not really understand the language or the meaning. A moment’s thought shows that examining by a script will miss many subtle features. The examination should thus be seen as a “planning process” in which many items enter the equation but not all will be relevant to this particular patient. There is thus a cycle of activity following the patient’s wish to seek treatment, involving questioning, examining, recording data in a variety of ways, collating the data, and planning from that data; the options are then brought back to the patient to complete the cycle.

The Examination Cycle

The examination cycle encompasses the patient’s hopes, their medical conditions, an orthodontic evaluation, a maxillofacial evaluation, the joint orthodontic and maxillofacial plan, and the patient’s responses to the orthodontic and surgical plans.

After completion of this examination cycle, the patient then moves on to definitive treatment. This may be “no treatment,” review and repeat the whole process later, or (and this is the most common outcome) proceed along an orthodontic/surgical/orthodontic route. It is essential that any progress along any of these routes is driven by a fully informed patient who comprehends all the options.

P. Ward-Booth

Clinical Examination

General Observations

The gender of the patient is important. For example, the male normally feels comfortable with a slightly prognathic jaw, but the female finds a small degree of prognathism gives an aggressive image. Cultural and racial differences are of course important, even with those races derived from the same ethnic group. From a British perspective (Figure 46.3), it is often noted that in certain parts of the United States a degree of prognathism in a female is attractive. Some British patients may be desperate to have a chin “reduced” that in United States terms would not appear to be a severe problem. Racial variations of “normal” can be much more marked.

The height of the patient can be important. Tall people tend to stoop and mask a prognathism. To what extent prognathism encourages a “head-down” posture is less certain. Examination of the patient standing up is thus extremely important. This is essential in cases of torticollis, which is not infrequently associated with plagiocephaly and scoliosis. Examination in a chair or, even worse, the restricting dental chair easily masks any scoliosis.

It is important to note the patient’s soft tissue structure. This may be an observation about obesity, which will certainly affect for example the outcome of a ramus “pushback” procedure, particularly in the chin-neck angle. Similarly, thin delicate nasal skin would certainly affect the outcome of a tip rhinoplasty, where every irregularity of cartilage surgery would be very visible. Thick soft tissues may reduce the amount of anteroposterior movement necessary for good aesthetics, compared with the pure skeletal examination.

Observations of Relevant Systemic Disorders

The age of the patient is important for three reasons. Is the patient mature enough to understand the indications for, and the nature of, the surgery? Will the surgery interfere with the normal facial growth? Will postsurgical growth negate the surgery? The first point is probably the most difficult to discern. The intellectual and emotional maturity of the adolescent is difficult to predict by only the chronologic age of the patient. A careful consultation, preferably at some point with the youngster on their own without a parent, usually reveals the maturity of the patient. It is very important that the problem is not significantly influenced by the parents. Parents normally fall into two clear groups; those who can see no problem with their child’s face and those who are trying to impose surgery. Fortunately most parents are in the first category, but are very aware of and understand that their child’s views are the most important.

The effects of surgery on facial growth remain confusing. The dramatic adverse effect of surgery in cleft lip and palate patients, particularly bony surgery, on facial growth inhibition

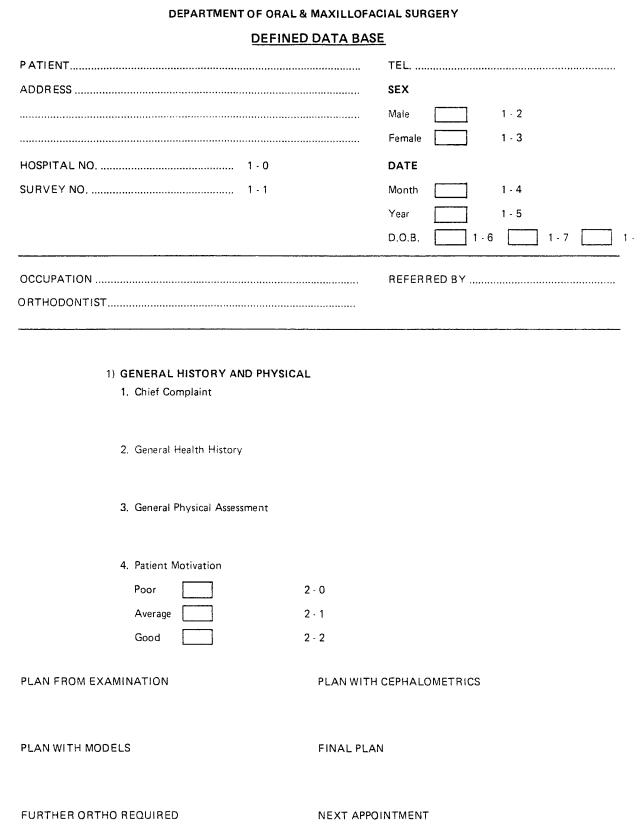

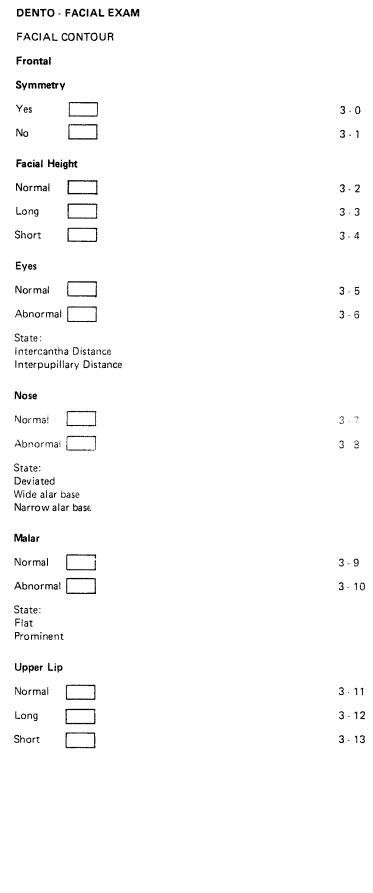

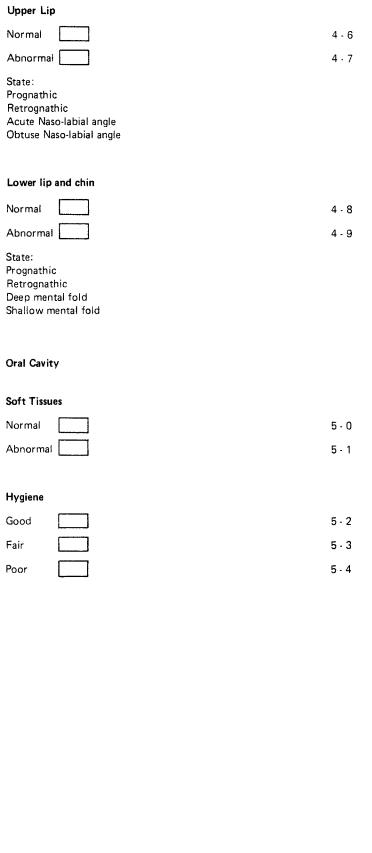

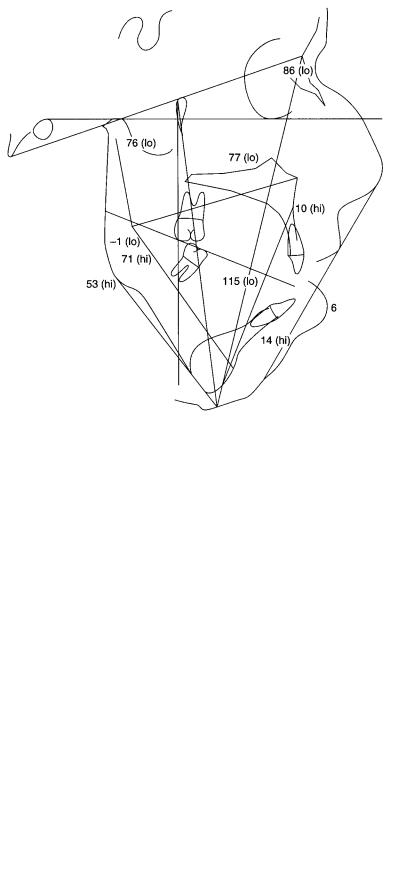

FIGURE 46.2 This systematic approach to the clinical appearance is too long for routine use, but provides a guide to planning for trainees.

Continued.

FIGURE 46.2 Continued.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

503 |

FIGURE 46.2 Continued.

FIGURE 46.2 Continued.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

505 |

FIGURE 46.2 Continued.

506 |

P. Ward-Booth |

FIGURE 46.2 Continued.

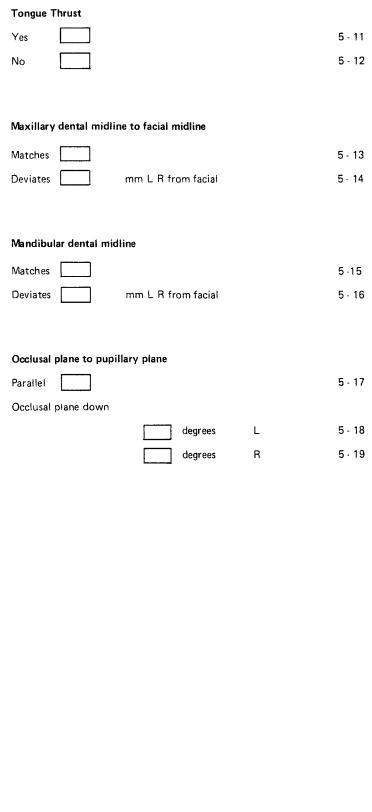

FIGURE 46.3 Although this patient remains somewhat prognathic, his appearance is quite acceptable with a normal occlusion.

has left a tradition that surgery stops facial growth. Orthognathic surgery in young growing teenagers does not, however, appear to have the same effects. Continued postsurgical facial growth may certainly account for “relapse.” The difficulty is knowing when facial growth has really finished. The growth curves for patients are known as the rapid growth phases for males and females are available.5 The problem is that statistics apply to groups of patients, not the individual patient facing the surgeon. Nevertheless, even informal questions to the patient and parents soon give a good indication how rapid the growth phase is and when it started. It is normally possible to be fairly certain in individual patients when the majority of growth has taken place.

Finally, clinically obvious pathology must be detected and identified. It would be essential to identify, for example, temporomandibular joint dysfunction before orthodontics or surgery was undertaken. Similarly, careful neurologic examination must be made.

Detailed Orthognathic Examination

For the examination to be useful, it must be logical and proceed in logical steps. The examination should encompass the following, and preferably in the order listed here.

1.The clinical examination should be of the full face and profile, systematically evaluating:

46. Orthognathic Examination |

507 |

Soft tissue

Hard tissue

Dentition

2.Radiologic material

3.Articulated models

Clinical Examination

The examination is conveniently divided into anterior and lateral (left and right), and the examination should start peripherally and finish at the occlusal level.

Anterior Examination, “Full Face”

There is sometimes a reluctance to examine full face for fear of not detecting the main problems. This is not true, and other features are detected that are often more important to the patient, who normally see themselves in this view (Figure 46.4).

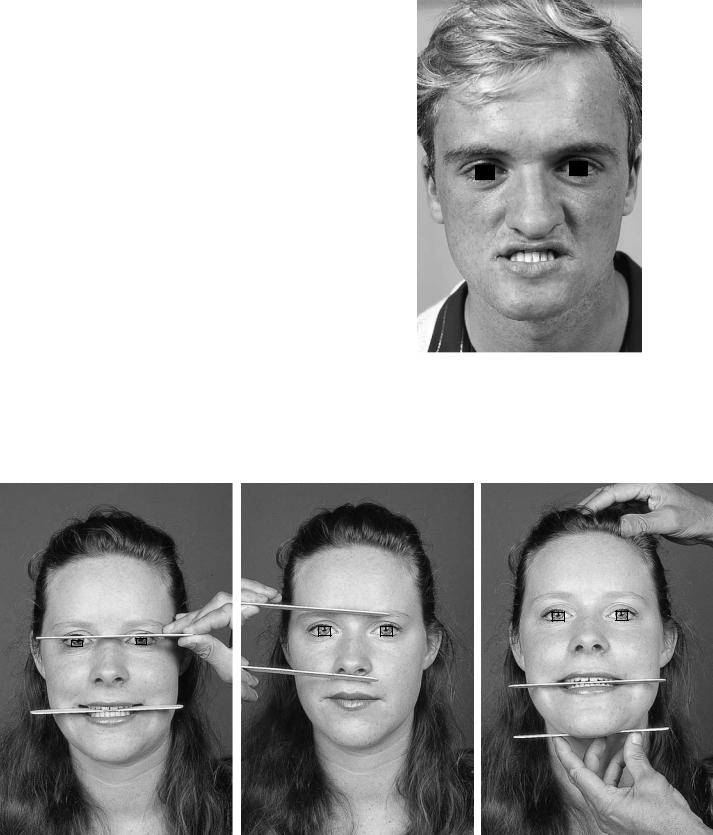

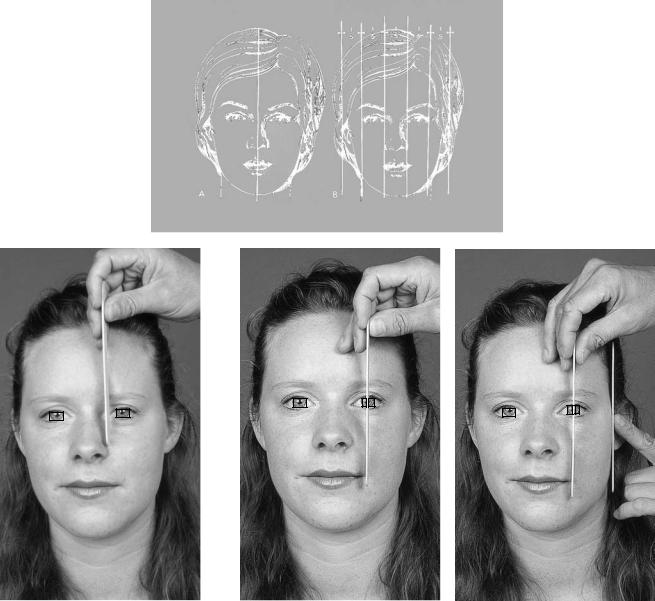

Pure “numbers” or measurements of facial size are not useful as we all come in varying sizes. What is important, however, is “ratios” or facial proportions of the full facial features. The method most frequently used is to divide the full face into those well-rehearsed equal “thirds” (Figures 46.5a–c): lower third, from the chin (menton) to base of nose (columella/labial junction); middle third, base of nose (columella/ labial junction) to bridge of nose (soft tissue nasion); and upper third, bridge of nose (soft tissue nasion) to the hairline

FIGURE 46.4 Full-face examination is often underused. It is the view the patient most frequently sees, and other subtleties may be exposed. This patient felt he looked too aggressive.

a |

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 46.5 (a) Division of the face into equal “thirds.” (b) The lower two-thirds as divided into the surgically useful upper and lower face heights. (c) Evaluation of the occlusal plane, noting its relationship to the pupils and the lower border of the mandible.

508

(a very poorly defined point). This approach is fine for trauma in which there can be loose descriptions of fractures (e.g., a mid-third fracture) but is not very useful, especially the upper third, for orthognathic planning. As it is absolutely essential to plan from the whole face, dividing the face into half may be more useful. In this instance, the upper half is from the soft tissue nasion to the top of the calverium, and the lower half from soft tissue nasion to menton; the lower half is then divided into equal thirds as before. This simple approach is very effective in highlighting variations from normal.

Similarly the width of the face can be assessed (Figures 46.6a–d). Here it is not quite so easy because the face tapers

P. Ward-Booth

from its widest point somewhere between the anterior end of the zygomatic arch and the mastoid prominence. The facial shape behind the ears is so influenced by the ears as not to be significant, and thus just anterior to the tragus is a useful “end point” to measure from, as well as along the line of the zygomatic arches, which are normally the widest point of the face. Exceptionally, in marked masseteric hyperplasia the gonial angles may be the widest point. Normally the gonial angles would be 2 to 4 mm medial to a vertical line dropped from the most prominent part of the zygomatic arches.

As with the vertical ratios, the width of the face can be evaluated with a series of linked ratios. The width of the face

a

b |

|

|

|

c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 46.6 (a) The center line is fundamental to planning. The widths of the canthii and pupils are best compared to other facial features, such as the lips, rather than relying on absolute measurements. (b–d) Clinical evaluation of facial width.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

509 |

is normally four times the interalar base width. The interalar base width is the same as the intercanthal. This however is quite varied, being only “correct” in 40% of patients; in about one-third, the interalar distance is 2 or 3 mm greater. Interestingly, in the United States a larger intercanthal than alar distance is considered a sign of attractiveness.

The intercanthal distance is normally equal to the distance between inner and outer canthi. The outer canthus is normally 2 to 4 mm higher than the inner canthus. A vertical line from the center of the pupils should mark the outer limits of the lips at rest (Figure 46.7). The amount of upper incisor visible at rest with the teeth apart is about 2 to 3 mm, and the upper teeth are visible to the first premolar.

Although the malar prominence forms one of the most important aesthetic landmarks in facial attractiveness, it is particularly difficult to define in the full-face view. The malar prominence is ideally broad, being an almost direct projection of the zygomatic arch (Figure 46.8). In the full-face view it is difficult to identify flat malars unless this is severe, as is seen in some cranial base syndromes such as Crouzons, where there may be excessive sclera display. There does however need to be a definable angle between the lower lid and the prominence caused by the malar, at the base of the orbicularis oculi.

The full-face examination is of course critical to document facial asymmetry. In many cases asymmetry is a progressive

FIGURE 46.8 Malar prominence is difficult to define both clinically and radiologically, yet is most obvious in grossly hypoplastic or prominent malars. This patient needs careful planning, as she has prominent malars yet is hypoplastic in the paranasal area.

feature and even in pure mandibular asymmetry it progresses subtly along the mandible; rarely is it seen as a definable volume of asymmetry. When this progressive asymmetry involves the face and skull, it becomes hard to define the volume that requires correction. A useful way to treat this problem is to take the face in its “thirds” and examine each portion and identify the center, ideally by temporarily covering the other “thirds” to avoid distraction. Thus, the center of the forehead is marked, then the soft tissue nasion and the center of the tip of the nose. Finally, turning to the lower “third,” identify the center of the upper and lower lips and chin. A wooden spatula is then placed along the marks to highlight the asymmetry. The dental midlines are noted. The patient with a poorly defined, diffuse asymmetry should be cautioned that complete craniofacial correction can rarely be achieved.

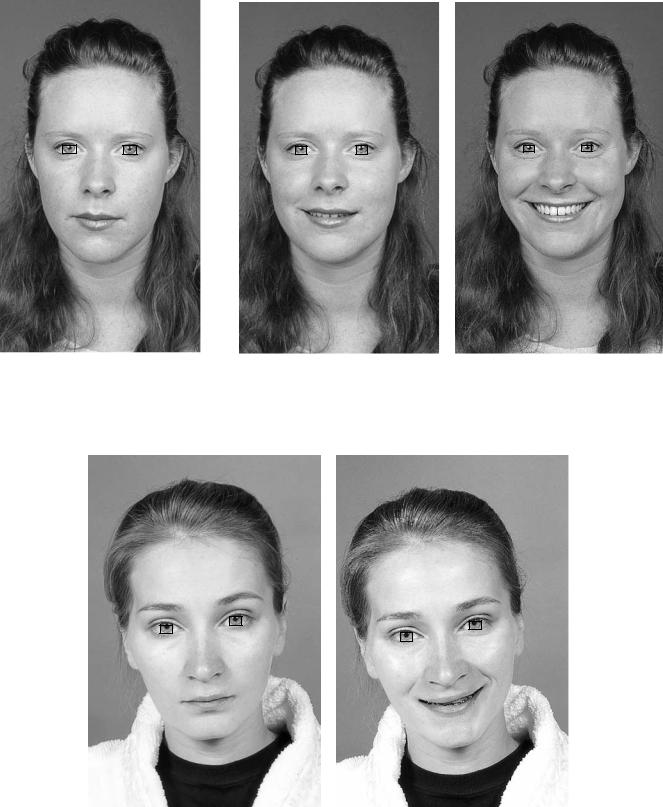

Incisor display is extremely important to note. This should be examined at rest, when smiling, and with a broad smile (Figures 46.9a–c). Evidence of forcing lip competence should be noted because this may invalidate “normal” incisor show. Vertical maxillary excess with a long lower face height and prominent incisors is normally easily detected; the failure to display incisors may be easily overlooked (Figure 46.10a,b).

Profile Examination

|

The profile observation is a very traditional approach to the |

|

examination and, sadly and erroneously, often the only clin- |

FIGURE 46.7 Hypertelorism and telecanthus in an Aperts patient. |

ical examination to be undertaken. It is important not to sim- |

|

510 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P. Ward-Booth |

|

a |

|

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 46.9 (a) Assessment of the incisor show is as important as it is difficult. “At rest” to the patient may force an unnatural tension in the muscle. (b) This view, however, represents her normal relaxed

incisor show, which is normal at about 2 mm. (c) It is important to get a big smile to ensure that there is not excessive gingival show, as this may have to be built into the surgical plan.

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 46.10 (a,b) Most surgeons and patients are very aware of the patient with vertical maxillary excess and excessive tooth and gingiva exposure. Care must be taken not to miss the patient like this with minimal incisor show.

46. Orthognathic Examination

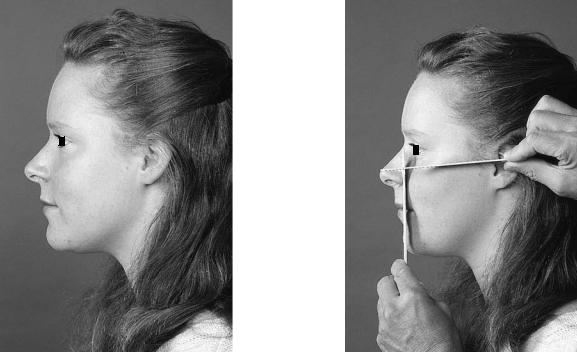

ply repeat the lateral cephalogram radiographic examination. It is particularly important to examine the whole face (Figure 46.11), neck, and posture of the head. These data cannot be easily obtained from the lateral cephalogram. The shape and position of the forehead, particularly the non-hair- bearing part, is absolutely critical to successful planning. The appearance of the neck-chin angle and form is again so important in predicting the outcome. Missing a fat bulky submental area and undertaking a mandibular “pushback” that will exaggerate this fold will certainly not remain unnoticed by the patient, who will be very concerned by this new “double chin.” Again, the examination can begin with the division of the profile into thirds or quarters, as described in the full-face examination. This should confirm the earlier findings.

Examination of the all-important forehead is difficult because there are few “numbers,” “angles,” or “projections” to guide the evaluation. The position of soft tissue nasion has an important relationship to menton. Often however it is important to assess the whole forehead up to the hairline, and this is not well documented. It is important to note the shape of the forehead with particular emphasis on a prominent or bossing appearance. Similarly, a steeply receding forehead should be noted. The forehead should incline from the vertical with the head in the natural head position, by 10° to 5°, with that of males being slightly more inclined. The line dropped ver-

511

tically from soft tissue nasion (Gonzalez-Ulloa)6,7 meeting a projected Frankfort horizontal at 90° should just touch soft tissue pogonion (Figure 46.12).

The nose, which is so important to aesthetics, has been well defined in the literature. The length of the nose should be contained in the division of the face into thirds and be about twice the height of the nasal tip to the base of the alar. The nose ideally should be 20° from the vertical, and the soft tissue nasion 3 to 4 mm posterior to the glabellar, to give a nasal frontal angle of about 130° (Figure 46.13). The dorsum of the nose is concave from a line from the soft tissue nasion to the tip by about 2 mm.

In orthognathic planning the nasiolabial angle is very important (Figure 46.14). The angle ranges from 95° to 105°, being more acute in females. Similarly, the relationship of the nose to the lower third of the face in profile is very important to planning. Ricketts has projected a line from nasal tip to soft tissue pogonion, and suggested the upper lip be 4 mm and the lower 2 mm behind this line8–11 (Figure 46.14). Steiner suggests a line from the soft tissue pogonion, at a tangent to upper and lower lips, should bisect the nose12,13 (Figure 46.15).

Even when armed with all these data on profiles, there still must be a systematic approach. One useful approach is to (1) evaluate the forehead relative to the rest of the face; (2) relate the forehead (soft tissue nasion) to the chin; (3) relate the

FIGURE 46.11 Profile examination is a chance to examine the whole face, neck, and posture.

FIGURE 46.12 A vertical from soft tissue nasion at right angles to Frankfort horizontal is a good way to relate the upper face to the lower and midface.

512

FIGURE 46.13 The frontal nasal angle (130°) is an important angle.

P. Ward-Booth

FIGURE 46.15 A line from nasal tip to pogonion relates the lips to nose and chin and is very useful in planning.

nose to the upper lip (nasolabial angle); (4) relate the lips to the nose; (5) compare the upper facial height to the lower facial height; and (6) evaluate malar prominence.

Dental Examination

From a purely surgical point of view, the dental examination is directed at establishing any dental factors that might impede a surgical plan. The presence of unerupted teeth or inadequate space for segmental procedures must be observed. Clearly, when dental infection or periodontal infection is present, elective surgery is contraindicated.

Because the surgeon does not have the expertise of the orthodontist in alignment or positioning of teeth before surgery, a dialogue must be established. The planned surgical movements, especially changes in occlusal plane angles, must be brought into the orthodontic planning process.

FIGURE 46.14 The nasolabial angle often reflects the relationship between the midface and lower face.

Radiologic Examination

Radiology has three very important roles

1.Identification of bony pathology, including a persistent growth center, for example, at the condyle

2.Record keeping; documenting presurgical, postsurgical, and follow-up positions of the facial bones

3.An aid to planning

46. Orthognathic Examination

Identification of Bony Pathology

Different medical-legal systems in different countries demand different levels of investigation. A thorough medical history and clinical examination must be taken and documented. In a patient undergoing elective surgery, a panoramic radiograph, which scans the teeth, mandible, and lower maxilla and sinus, is necessary. If these examinations suggest other pathology then it may be appropriate to have a more detailed or extensive radiologic examination. In most cases, this type of examination usually reveals no more than impacted third molars. Many surgeons feel these should be removed prophylatically before orthognathic surgery, especially for ramus procedures.

Naturally significant bone pathology such as cysts must be identified. In asymmetric cases, attention should be drawn to the condyles as well as the extent of the asymmetry of the mandible. Diagnosis of persistent and asymmetric growth at the condyle is most certainly made by detecting it on repeat articulated models. The use of bone scans to detect continued growth is not as useful as once declared. In the first instance, the injection of a radionucleotide into any patient who might be pregnant is unacceptable, and unfortunately the results of scans in any patient are frequently equivocal. The problem is that in patients with enlarged condyles there is often some traumatic TMJ dysfunction producing some inflammation, and this will provoke an increased uptake of isotype. Thus, it may be difficult to diagnose continued bone apposition from inflammatory changes.

The panoramic radiograph will normally suggest where the pathology lies by showing either an enlarged condyle or a diffuse enlargement of the mandible. As with the scan, to demonstrate continued activity is much more difficult. The use of sequential study models is the most reliable if slow method of evaluating continued growth.

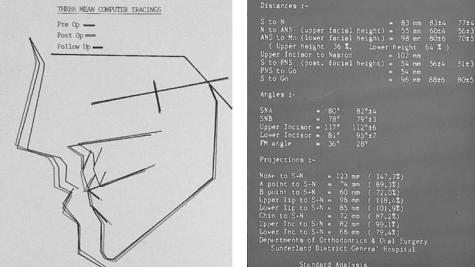

Record Keeping

It is only good clinical practice to audit the effectiveness and stability of orthognathic surgery. The use of the standard lateral cephalogram to document the position of the facial bones before surgery, immediately postoperatively, and then at subsequent follow-up visits is clearly the best way of documenting the movements achieved and the long-term stability (Figures 46.16a,b). The radiographs must include at least immediate preand postoperative films. Immediate postoperative films may be confused by the need to use final occlusal splints. The timing of long-term follow-up films is not as critical, but most surgeons would expect 3-, 6-, and 12-month films. Although it is important academically to document longer-term stability, the majority of the relapse and soft tissue settling occurs early.

The cephalometric landmarks used for auditing stability are usually those used in the planning process, but other landmarks or projections may be useful for specific audits of groups of patients. These cephalometric landmarks will be discussed in the planning section.

513

a

b

FIGURE 46.16 (a) This approach seems more informative. The line bisects the “S” curve of the nose and upper lip. (b) Clinical use.

In patients in whom rigid maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is used, it is important to ensure the condyles have not been distracted from the fossa. Unfortunately, simple standard x-rays are not reliable and specialized views are needed, like reverse Townes, transpharyngeal, or even CT scans. The use of rigid MMF is however quite rare.

Aid to Planning

It would be naive not to assume that there are some surgeons who use lateral cephalometrics as the only method of planning orthognathic surgery. Some clearly “get away” with this method, but it is less than desirable. Even very well executed films have inherent errors. The film is converting a

514

three-dimensional object to a two-dimensional plane. There is disproportionate magnification, from 15% at one side to 0% where the skin touches the cassette. Any vertical movement of the bones is accompanied by rotation at the condyles, and these structures have the most marked magnification errors. The majority of cephalometric analysis predominately measures the dental structures and rarely considers the head, face, and neck as a whole. Many orthognathic surgical planning programs exclude the forehead in the planning process, a potentially disastrous error. In some patients and particularly in some syndromes, the skull base, which forms the “starting” point of most angular and linear measurements, is not a “standard” shape or position. If the surgical procedure is defined by cephalometric data, the wrong aesthetic result may ensue. It is essentially a “dental” examination for a facial problem. In planning, cephalometrics should thus be used as confirmation of the careful clinical examination and as a guide to the orthodontic movements needed.

This chapter does not provide the data that are available in textbooks on cephalometrics, but it is useful to highlight some of the analyses available. The very basic assessment is the measurement of vertical height ratios, nasion to anterior nasal spine (ANS), and ANS to menton. Angular measurements of SNA and SNB give useful information about the relative positions of the maxilla and mandible. Angular measurements of the occlusal plane angle may be helpful in anterior openbite cases of those with anterior or posterior height discrepancies. Finally, the angulation of the incisors should be noted. The British orthodontists have developed a surgical planning program that provides a relatively simple analysis, with the option for the more commonly used surgical procedures. It takes a small “window” of the face and is limited as a planning device, but is useful in trying some surgical options.

P. Ward-Booth

It recognizes that the soft tissue responses to bony movements are very much a “guess.” The risks of planning from radiographs only cannot be stressed enough (Figures 46.1g,h). In this case, failure to appreciate the forehead and nasion prominence has produced a distressing result.

The Delaire analysis attempts to overcome many of the shortcomings of conventional analyses.14–16 This method plans from the whole skull and neck and seeks to establish proportions. It has some disadvantages, particularly the need to have a penetrated view of the whole skull, with use of increased irradiation. It is a little more complex than other procedures, but those routinely using the technique report familiarity renders it no more difficult than most analyses. As with all systems, the Delaire analysis inherently has errors of point recognition, and is converting a three-dimensional head to a two-dimensional film.14–16 Again, despite its attempt to evaluate the whole head, it fails to document the important relationship of the forehead to the facial skeleton. This analysis is not readily available in a computer system, but a number of analyses are available (Figures 46.17a,b). Some integrated programs like OTP (Ortho Treatment Planner), Pacific Coast Software, Inc. have the option of warping the soft tissue image to reflect the procedure and adjust the image according to the surgical program. All these devices must be carefully explained to the patient because the quality of the printout can easily mislead the patient to believe this will be the final result (Figures 46.18a–f).

The use of “surgical templates,” that is, transparencies of Bolton standard heads and faces, seems too easy to be taken seriously.17 There are three sizes of Bolton standard faces marked on a transparent film, which is simply placed over the cephalometric radiograph. This technique does however have the benefit of giving a good overview of the whole face,

a |

b |

FIGURE 46.17 (a) Record keeping can be done by cephalometric computer storage. (b) Using a variety of measurements.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

515 |

FIGURE 46.18 (a) Rickett’s analysis. (b) McNamara’s |

a |

analysis. (c) A simple analysis. (d) Planning program |

|

of UK orthodontists; this ignores the forehead. (e) |

|

Digitized points on O.T.P. Planner. (f) Surgical treat- |

|

ment, maxilla impaction, mandible advance and ro- |

|

tate. |

|

Continued. |

|

b

516 |

P. Ward-Booth |

c

d

FIGURE 46.18 Continued.

46. Orthognathic Examination |

517 |

e

f

FIGURE 46.18 Continued.

518

often omitted in some of the more sophisticated analyses. Its main disadvantage is its inability to “measure” the movements required to obtain a harmonious appearance. There are many other analyses that provide much more comprehensive data, hopefully leading to a better diagnosis of the clinical problem. The Delaire analysis is particularly interesting as it attempts to find a more stable “starting point” or base to the analysis.14–16 It also includes a much more complete analysis of the facial skeleton.

Model Surgery and Planning

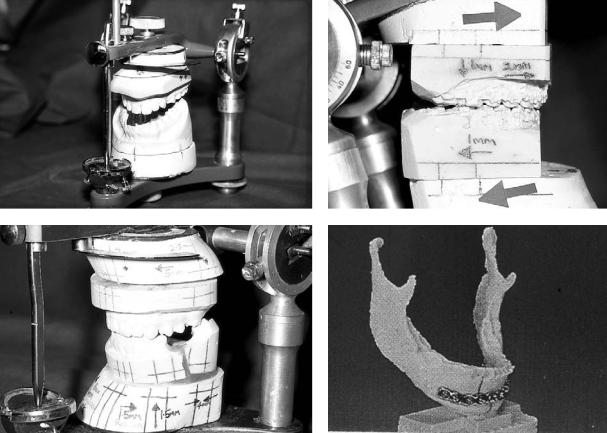

Although this step is at the end of the planning cycle, it is most important. Good model surgery gives the surgeon more real information about the three-dimensional movements his osteotomy will allow to occur. This is so important with modern rigid internal fixation, because any errors of fixation will be looking at the surgeon the next day!

The aim is to obtain good articulated models with the correct bite. The bite is often erroneously recorded because patients needing osteotomies have malocclusions. This may well

a

c

P. Ward-Booth

produce a slightly postured bite of convenience and comfort that involves a small distraction of the condyle from the fossa. Although it may not be accurate, the use of an articulator does help to establish the occlusal plane angulation and the possible axis of rotation of the mandible (Figures 46.19a–d).

The models should be accurately mounted with adequate measurements, so that the osteotomy cuts can be made and the movements simulated. This identifies any inappropriate or potentially unstable movements. This problem classically occurs in anteroposterior movements that increase the vertical height, and only if the models are cut and moved anatomically can these unstable vertical movements be picked up.

Good model surgery also helps to ensure accurately constructed intermediate and final splints. The “Achilles heel” of model surgery is accurately documenting the position of the condyle and the point of rotation of the mandible. The condylar position almost certainly changes from the awake to the anesthetized to the postoperative positions. Postoperative evaluation of the actual rotations that occur show an unpredictable and wide range of rotation points, making preoperative predictions impossible.

b

d

FIGURE 46.19 (a) Model surgery is extremely important in visualizing the presenting position. (b) Planned movements. (c) Great care is required at all stages of preparation; it is not however totally ac-

curate, especially in rotational movements. (d) Computer-generated models from CT give much greater accuracy but the amount of irradiation and cost preclude this as a routine procedure.

46. Orthognathic Examination

Completing the Planning Cycle

Completion of planning entails collating all the data, resolving a definitive plan, and then presenting the options to the patient. In most cases, planning will begin before orthodontic work and so at that stage a provisional plan will be presented to the patient. The patient must be informed that this plan will be reviewed at the end of orthodontic work once the projected tooth movements become a reality. Other supplementary surgery, for example, removal of impacted teeth, may be undertaken during the orthodontic process.

At this consultation it is important to inform the patient

a

b

519

about the surgery, its potential complications, and what the patient should expect. Arranging for the patient to see a recently operated patient is an excellent way of “informing” yet not frightening the patient. The patient must however accept there will always be a variation in outcome and in the patient’s response to the surgery (Figures 46.20a,b). Warning of possible damage to the infraorbital and particularly the inferior alveolar nerves must be conveyed to the patient.

The stability of the surgery must be discussed briefly with the patient. The current evidence suggests that small movements are more stable than large movements, 7 to 8 mm being the boundary between large and small. The stability of

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 46.20 (a) Postoperative complications are important to dis- |

the same surgeon. (b) The patient’s response is also difficult |

||||

cuss with the patient. Nerve damage and swelling are always diffi- |

to gauge preoperatively; minimal postoperative swelling. |

||||

cult to predict. Both these patients had mandibular procedures by |

|

|

|

||

520 |

P. Ward-Booth |

a

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b |

|

c |

|

|

|

|||||

d |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

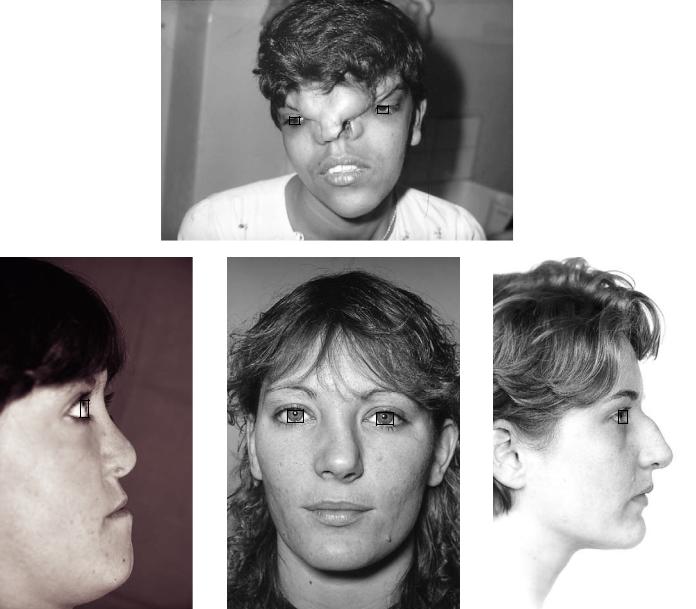

FIGURE 46.21 (a) The surgeon must have the surgical repertoire to give the patient the operation the planning demands, rather than a “favorite” operation. (b) An example of Binders syndrome. (c) Posttraumatic nasal deformity. (d) Congenital nasal deformity.

the soft tissue is equally important but less predictable.18 Finally, the surgeon must feel happy to undertake the

surgery that the patient needs and not be restricted by surgical convenience or preference. As with all surgery, “the commonest conditions present most commonly” and the majority of patients need standard routine procedures. There will be a small group of patients, however, presenting with more unusual needs, and the maxillofacial surgeon should be able to treat them equally well (Figures 46.21a–d).

References

1.Proffit WR, White RP. Who needs surgical-orthodontic treatment? Int J Adult Orthod Orthogn Surg. 1990;5(2):81–89.

2.Flanary CM, Barnwell GM, Van Sickels JE, Littlefield JH, Rugh AL. Impact of orthognathic surgery on normal and abnormal personality dimensions: a two-year follow-up study of 61 patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;98 (4):313–22.

3.Serra Payro JM, Vinals Vinals JM, Palacin Porte JA, Estrada

46. Orthognathic Examination

Cuixart J, Lerma Gonce J, Alacron Perez J. Surgical management of the acromegalic face. J Craniofac Surg. 1994;5 (5):336–338.

4.Phillips S, Bailey LJ, Sieber RP. Level of agreement in clinicians’ perceptions of class II malocclusions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(6):565–571.

5.Tanner JM, Davies PSW. Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children. J Paediatr. 1985;107:317–329.

6.Gonzales-Ulloa, M. Planning the integral correction of the human profile. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1961;36:364–373.

7.Gonzales-Ulloa M, Stevens E. The role of chin correction in profile plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;41:477–486.

8.Ricketts RM. Planning treatment on the basis of the facial pattern and an estimate of its growth. Angle Orthod. 1957;27:14–37.

9.Ricketts RM. Cephalometric analysis and synthesis. Angle Orthod. 1961;31:141–156.

10.Ricketts RM. Perspectives in the clinical application of cephalometrics. Angle Orthod. 1981;51:115–150.

11.Ricketts RM. The value of cephalometrics and computerized technology. Angle Orthod. 1972;42:179–199.

521

12.Steiner CC. Cephalometrics in clinical practice. Angle Orthod. 1959;29:8–29.

13.Steiner CC. Cephalometrics as a clinical tool. In: Kraus BS, Reidel RA, eds. Vistas in Orthodontics. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1962.

14.DelaireJ.L’analysearchitecturaleetstructuralecraniofaciale(deprofil); principles théoriques; quelques exemples d’emploi en chirugie maxillo-faciale. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1978;79:1–33.

15.Delaire J. Quelques pièges dans les interpretations des téléradiographies cephalometriques. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1984;85:176–185.

16.Delaire J, Schendel SA, Tulasne JF. An architectural and structural craniofacial analysis: A new lateral cephalometric analysis. Oral Surg. 1981;85:226–238.

17.Broadbent BH Sr, Broadbent BH Jr, Golden WH. Bolton Standards of Dentofacial Developmental Growth. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co., 1975.

18.Hack GA, de Mol van Otterloo JJ, Nanda J. Long-term stability and prediction of soft tissue changes after Le Fort I surgery.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;104(6):544–555.