Essentials of Orthopedic Surgery, third edition / 05-Children’s Orthopedics

.pdf

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

189 |

Physeal Damage

Injury to the plate can have long-term effects, especially when it occurs in a very young child with significant growth remaining. Complete arrest and subsequent limb-length inequality or partial arrest and the resultant angular deformity are the two standard patterns of postinjury deformity.

Pathologic Fracture

Although infected bone frequently looks more dense (i.e., sclerotic) on an

X-ray, it should not be assumed that it is mechanically stronger. In point of fact, the dense bone is disorganized, its lamellar pattern is disrupted, and therefore it is mechanically less sound. Pathologic fracture can occur even in the immobilized limb, although the risk is less.

Chronic Infection

Despite aggressive treatment, some infections are not completely eradicated, and a “stalemate” is established between the host and the organism. Occasionally, at times of psychologic or environmental stress, the infection will reactivate and produce additional damage (see Chapter 3).

Arthritis in Childhood

Juvenile Rheumatoid Disease

Frequently referred to as Still’s disease, juvenile rheumatoid disease (JRA) is the most common connective tissue disease in children. In fact, George Still specifically described the systemic form of the illness. Children have systemic symptoms—fever, rash, hepatosplenomegaly—and develop a polyarticular arthritis. This is the most destructive form of the disease and leaves multiple destroyed joints in its wake.

The other two forms of the disease are definitely less virulent. Polyarticular disease, as the name implies, takes its toll on the joints, but is not associated with systemic findings. Pauciarticular JRA is the most common and the most benign form of the disease. Typically, it is a monarticular arthritis, with the knee, elbow, and ankle being the joints most commonly involved. Frequently, children suffering from the pauciarticular form of the disease present with an isolated chronically swollen joint. This finding should trigger a diagnostic workup. Diagnostic blood studies are usually negative (rheumatoid factor is positive in only 10% of cases). X-rays usually only show juxtaarticular osteopenia, and frequently a synovial biopsy may be needed (Fig. 5-15). The histology of the synovium is similar to that of the adult disease; namely, hyperplasia and villous hypertrophy of the synovium. It is imperative to recognize that JRA is the leading cause of blindness in children because of the destructive iridocyclitis that can

190 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

accompany the joint disease. All children with JRA should be under the care of an ophthalmologist because eye involvement does NOT parallel the degree of joint involvement; those with minimal joint disease can have the most severe eye changes.

Treatment should be directed toward control of the synovitis with medications, physical therapy to maintain joint motion, psychologic support for those chronically impaired children, and ultimately arthroplasties or fusions for those joints most severely involved.

Hemophilia

Children with bleeding dyscrasias frequently have repeated hemarthroses. Initially, the blood in the joint simply distends the capsular structures and causes a mild synovitis. With repeated bleeds, the synovium becomes hyperplastic and ultimately pannus formation is seen. At this point, the joint changes appear very similar to those seen in rheumatoid disease, such as osteopenia, enzymatic cartilage degradation, bony erosions, and lysis (Fig. 5-16).

Lyme Disease

In the endemic regions of the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states, the child who presents with a swollen knee needs to be considered as a poten-

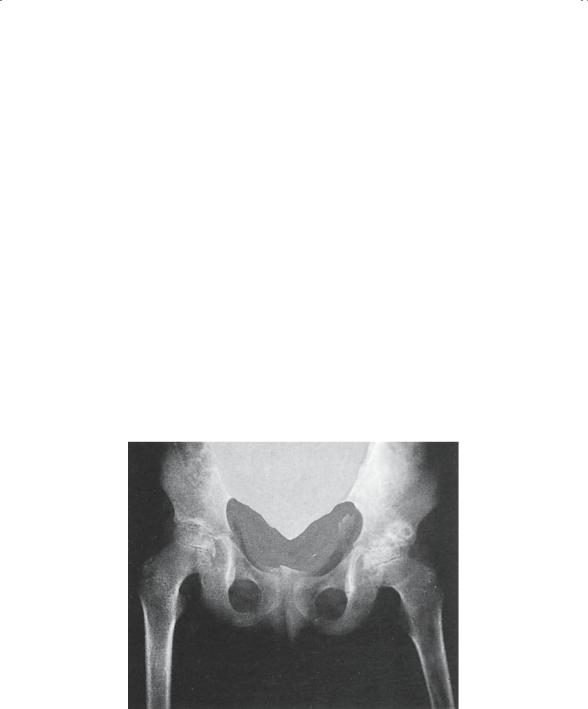

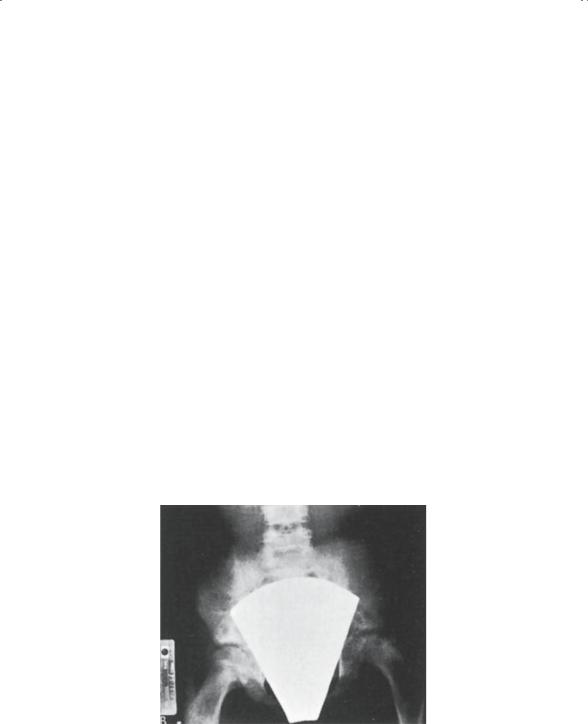

FIGURE 5-15. Rheumatoid arthritis of both hips. Radiogram of hips taken 3 years later. The child was allowed to be ambulatory without protection of the hips. Note the destructive changes with fibrous ankylosis on the right and bony ankylosis on the left. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

191 |

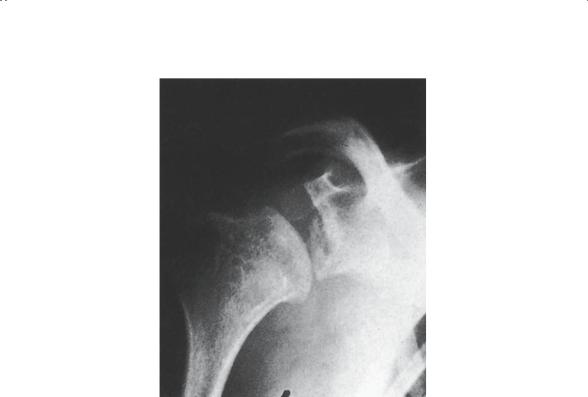

FIGURE 5-16. Hemophilic arthropathy of shoulder. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

tial victim of Lyme disease. This infectious arthritis is caused by a specific spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. The organism is transmitted to the human host by the bite of a deer tick. These ticks are significantly smaller than the common wood tick, and they are barely visible with the naked eye. Unfortunately, a history of a bite is rare and usually the diagnosis is reached by a high index of suspicion in a susceptible host. The combination of endemic region, erythematous annular skin lesions, and monarticular arthritis should lead the physician to order a Lyme titer.

Treatment is generally successful if begun early. Occasionally, despite adequate treatment, the arthritis can progress to chronic joint destruction, mandating further care.

Metabolic Disease

Perhaps the classic metabolic disease to affect the pediatric skeleton is rickets. The etiologies of rickets are multiple (Table 5-1), but the important pathophysiologic step is a relative paucity of vitamin D. It will be remembered that vitamin D is essential for normal progression of physeal bone

192 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

TABLE 5-1. Etiologies of rickets.

1.Vitamin D dietary deficiency

2.Malabsorption states

3.Renal rickets

a.Tubular defects (generally congenital)

b.Glomerular disease (generally acquired)

4.Miscellaneous causes

a.Associated with neurofibromatosis

b.Complication of Dilantin therapy

development, and without it provisional calcification will not occur in the deepest layer of the growth plate.

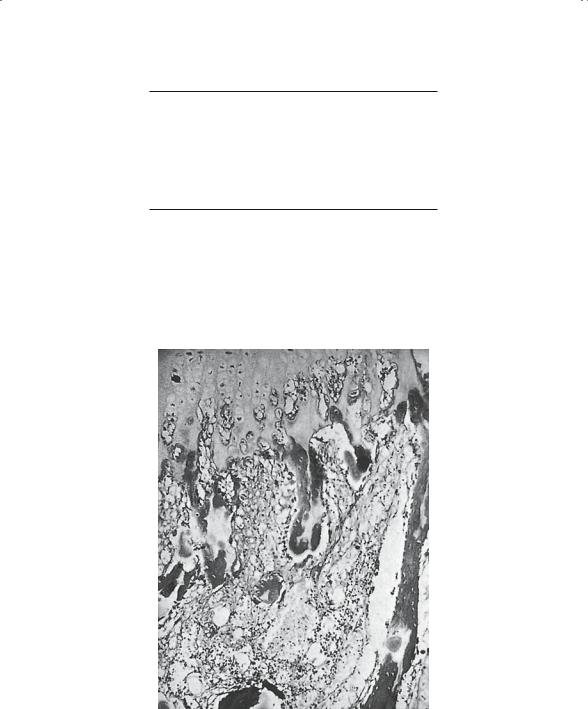

As a result, physeal disorganization (Fig. 5-17) can be anticipated with subsequent physeal widening, trumpeting of the metaphysis, and aber-

FIGURE 5-17. Histologic appearance of rickets. Micrograph through the epiphy- seal–metaphyseal junction. Note the uncalcified osteoid tissue, failure of deposition of calcium along the mature cartilage cell columns, and disorderly invasion of cartilage by blood vessels (× 25). (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

|

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

193 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

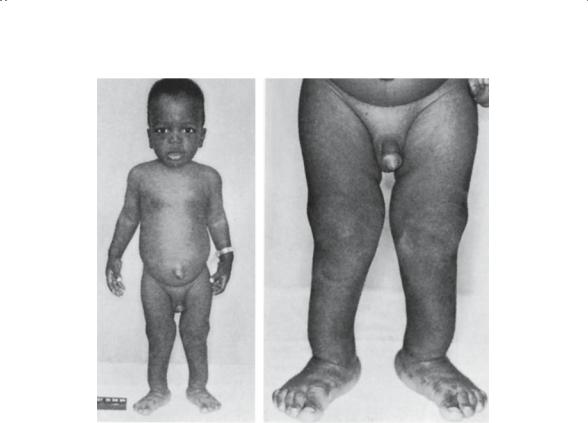

A B

FIGURE 5-18. Simple vitamin D deficiency rickets. (A, B) Clinical appearance of patient. The legs are bowed anterolaterally. Note the protuberant abdomen with the umbilical hernia. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

rant enchondral bone growth. The clinically apparent changes of knobby joints, beading of the costochondral joints, and genu varum are all phenotypic reflections of the underlying histologic disruption of bone formation (Fig. 5-18).

Depending on the etiology of the rickets, the histologic pattern varies slightly, but the overall skeletal changes remain relatively constant.

Vascular and Hematologic Disease

Vascular diseases of the pediatric skeleton are typified by osteochondroses such as Perthes’ disease of the hip and Osgood-Schlatter’s disease of the knee. These are considered regionally, leaving the hematologic diseases to be discussed here.

194 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

Sickle Cell Disease

The red cell deformation that occurs in sickle cell patients caused by the abnormal hemoglobin is responsible for the skeletal changes. The abnormally shaped cells cause stasis and sludging in small arterioles and capillaries. The effect, as expected, is disrupted flow and bony necrosis. The bony infarcts seen in sickle cell disease can occur anywhere in the bone but are more typical in the metaphysis (Fig. 5-19).

These children are also predisposed to osteomyelitis, probably because of the already sludged vessels in the metaphysis, making bacterial trapping even easier. Even though Staphylococcus is the most common organism retrieved, this patient population is also susceptible to infection with Salmonella. This organism gains access to the circulatory system through small infarcts in the intestinal wall and then enters the bone hematogenously. The incidence of Salmonella osteomyelitis is approaching that of Staphylococcus in this population.

The treatment for the infarcts is appropriate hematologic care, such as hydration and analgesics. Antibiotic selection for osteomyelitis should take into consideration the incidence of Salmonella.

Leukemia

Leukemia is the most common malignancy of childhood, and the skeleton is not spared its ravages. The bones by X-ray show nondescript lytic changes, most characteristically seen in the metaphyseal region and referred to as

FIGURE 5-19. Sickle cell disease in an 11-year-old girl. Anteroposterior radiogram of the hips. Note the avascular changes in the left femoral head. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

195 |

FIGURE 5-20. Bone manifestations of acute leukemia. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

metaphyseal banding (Fig. 5-20). The areas of osteopenia parallel and are adjacent to the physis; although suggestive of leukemia, they are NOT pathognomonic of it.

Although usually the diagnosis has been made well before skeletal complications develop, occasionally a child will present for the evaluation of “growing pains” only to have a workup reveal this disease. Ordinarily “growing pains” occur in children 2 to 7 years of age, affect primarily the legs, are symmetrical (although not simultaneous), occur in early evening or just after going to bed, and are NOT associated with any systemic complaints. Any variation from the usual pattern should suggest a basic workup to include X-rays and a white count with differential.

Congenital and Neurodevelopmental

This group is the largest and most nondescript “wastebasket” of pathologic states, many of which have severe impact on the pediatric skeleton. Included here are congenital birth defects of no known etiology, such as proximal

196 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

femoral focal deficiency, as well as genetic diseases transmitted in classic Mendelian fashion (e.g., hemophilia) or caused by chromosomal defects (e.g., Down syndrome).

In addition, the neuromuscular diseases frequently have an immense impact on the skeleton, as aberrant and eccentric muscular forces are created. Unfortunately, it is difficult to find many common themes that make an appreciation of the skeletal impact easier to understand.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

This disease is transmitted in a classic autosomal dominant pattern with only rare exception. The basic defect is one of abnormal collagen synthesis caused by impotent osteoblasts. For this reason, it has been grouped with other “sick” cell syndromes. Certainly, the osteoblasts are normal in number but are incapable of normal synthetic activity. The collagenous product of their incompetence is poorly formed and poorly cross linked, making it weak. The subsequent bone that is made is similarly architecturally thin and mechanically weak.

The severity of the disease is as expected, a function of the dose of abnormal genetic material. Some of the severe homozygotes are stillborn as a result of intracranial bleeds occurring in the perinatal period. As with most genetic diseases, penetrance varies such that some children have multiple fractures and severe shortening and others, less involved, have only the occasional fracture.

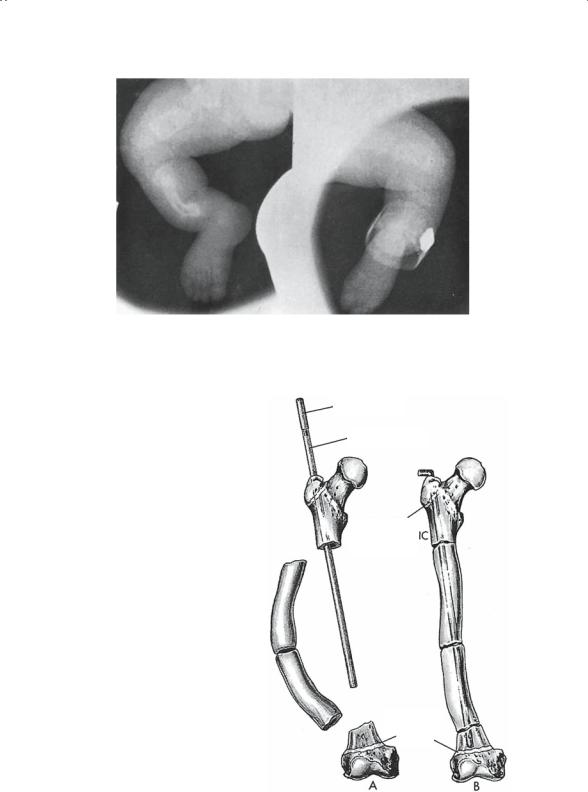

Typically, the bones are osteopenic (Fig. 5-21), with thinned cortices and decreased diameter. Multiple fractures with resulting deformities are the norm. These fractures respond to appropriate treatment, and healing is only slightly prolonged. Occasionally, it is necessary to correct long bone deformities, which is best accomplished operatively by performing multiple osteotomies in a single bone (Fig. 5-22) and lining the resultant fragments up on an intramedullary rod (Sofield “shish kabob”).

Scoliosis can also complicate this disease, and its management can be very challenging, especially if surgical management is required to correct the deformity. It is very difficult to use spinal instrumentation in the face of this osteopenic, softened bone.

Down Syndrome

First described in England by Langdon Down in the 1800s, this syndrome has been shown to result from a trisomy of the number 21 chromosome. It is the most common chromosomal abnormality that we see today, and it occurs in approximately 1 in 500 to 800 live births based on the age of the mother. Because of its frequency, it is the prototype for the other chromosomal abnormalities, and the orthopedic manifestations tend to be somewhat common to all.

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

197 |

FIGURE 5-21. Osteogenesis imperfecta congenita in a newborn. Radiogram of lower limbs, showing multiple fractures. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

FIGURE 5-22. Williams modification of Sofield–Millar intramedullary rod fixation. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

Male part

Female part

Greater trochanteric apophysis

apophysis

Distal femoral

physis

A |

|

B |

198 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

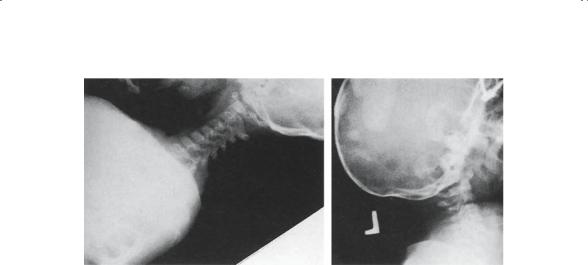

FIGURE 5-23. Atlantoaxial instability in Down’s syndrome. (From Tachdjian MO. Pediatric Orthopedics, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1990. Reprinted by permission.)

Hypotonia and ligamentous laxity typify the group. The ligamentous laxity results from an inordinate number of elastic fibers relative to the number of collagen fibers in ligament and joint capsule. The joint changes typical of this disease and other chromosomal diseases can be traced directly to this ligamentous laxity. Specific manifestations include the following:

1.C1–C2 instability (Fig. 5-23): Because of laxity of the transverse ligament of the odontoid process, anterior translation of C1 on C2 occurs, frequently to alarming degrees. Routine lateral cervical spine radiographs in flexion and extension should be regularly obtained in these children to evaluate them for this problem.

2.Hip subluxation and dislocation can occur insidiously over time, again resulting from the capsular laxity about the joint.

3.Patellar subluxation is the cause of the typical gait seen in the older child with Down syndrome. These children often walk with a stiff-legged gait in an effort to preclude patellar subluxation.

4.Hypermobile flat feet and bunions.

The management of these orthopedic problems is primarily directed at controlling the deformity, if possible, and minimizing the pain, which is rarely a significant problem. Despite fixed deformities, it is frequently surprising how well these children are able to compensate.

Skeletal Dysplasias

There are several hundred recognized skeletal dysplasias, each with its own unique clinical characteristics and specific skeletal abnormalities. It