Essentials of Orthopedic Surgery, third edition / 05-Children’s Orthopedics

.pdf

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

249 |

patients with juvenile kyphosis. A thorough neurologic examination is mandatory to rule out spastic paraparesis, which would suggest other possible diagnoses including congenital kyphosis, intraspinal anomaly, or thoracic disk herniation. Standing PA and lateral radiographs of the entire spine are obtained. Kyphosis is measured using the Cobb technique, and the lateral X-ray is scrutinized for findings of Scheuermann’s disease, as already described. A mild scoliosis is frequently seen radiographically. In addition, it is important to check for the presence of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis, which has been reported to be increased in prevalence in patients with Scheuermann’s disease.

Patients with hyperkyphosis can be treated with observation, bracing, or surgery. Observation, frequently accompanied by a program of thoracic extension exercises, is utilized in patients with postural kyphosis or without evidence of clear-cut progression in cases of Scheuermann’s disease. Bracing is indicated for patients with structural kyphosis who have clearcut evidence of progression of the curve and have at least 18 months of growth remaining. Because underarm orthoses are ineffective in this condition, Milwaukee brace treatment is required in most cases. In contrast to scoliosis, Scheuermann’s kyphosis responds in many cases with longlasting curve improvement following successful brace treatment. It should be noted, however, that patients with larger curves, in excess of 70 to 75 degrees, frequently lose correction following cessation of bracing.

Because of the usually benign natural history of Scheuermann’s kyphosis, surgery is rarely indicated. Bracing should be attempted in most patients with adequate growth remaining because long-lasting curve improvement may result. Surgery is usually reserved for individuals who do not respond to brace treatment, who have curve progression in the brace, or who have severe curves, usually in excess of 80 to 90 degrees, that are not likely to respond to bracing and represent a potentially significant functional and cosmetic deformity. Surgery is also undertaken, on occasion, in adults with intractable thoracic back pain that does not respond to a nonoperative program of exercise and NSAIDs. These individuals usually have curves in excess of 65 to 70 degrees.

Surgery for the patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis consists of a spinal fusion with instrumentation. The fusion extends from just above to just below the area of kyphosis, typically over 10 to 12 levels. Flexible curves, which can be reversed to 55 degrees or less on hyperextension, may be treated with a posterior spinal fusion with compression instrumentation. More-severe or more-rigid curves are treated with anterior diskectomies and release of the hypertrophied anterior longitudinal ligament, followed by posterior fusion with instrumentation. Surgery typically results in excellent curve correction, ranging from 30% to 50% in most series of combined anterior and posterior surgery, which usually reduces the kyphosis into the normal range. Cosmetic improvement is significant, but when the surgery is undertaken for pain relief the results are uncertain. Complications of

250 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

surgery include infection, implant failure, and neurologic injury. Junctional kyphosis, the development of kyphosis above or below the end of the fusion, may be seen as well. It should be stressed that the surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis is rarely employed, and the surgeon, the patient, and the patient’s parents need to view the natural history of this disorder in the context of the magnitude of the surgery required, usually a combined anterior and posterior approach.

Spondylolisthesis

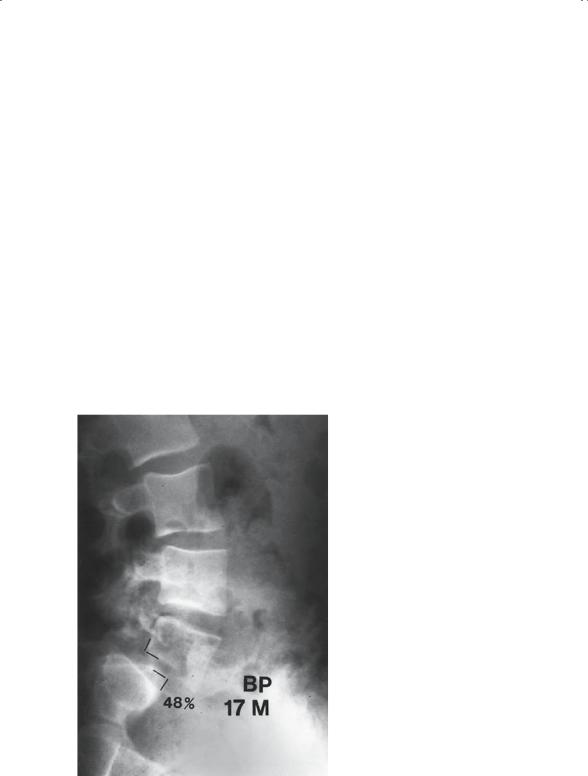

“Spondylolisthesis” refers to the forward slippage of one vertebra on that below it. First described by Herbiniaux, a Belgian obstetrician, this condition has been extensively studied and reported. Spondylolisthesis is most common in the lower lumbar spine, particularly at L5–S1, and is a common cause of back pain in children and adolescents (Fig. 5-59).

Spondylolisthesis has been classified by Newman (Table 5-3). The most common types are type II, isthmic, and type III, degenerative. Degenerative spondylolisthesis occurs in middle-aged and older adults as a result of

FIGURE 5-59. A 17-year-old boy with a 48% (grade II) isthmic L5–S1 spondylolisthesis.

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

251 |

TABLE 5-3. Classification of spondylolisthesis.

Type I: Dysplastic—congenital dysplasia of the S1 superior articular facet, or L5 inferior facet.

Type II: Isthmic—a defect in the pars interarticularis

a.stressor fatigue fracture

b.elongated but intact pars

c.acute traumatic pars fracture

Type III: Degenerative—degenerative changes in the disc and facet joints allowing subluxation.

Type IV: Traumatic—acute fracture, other than in the pars (e.g. facet, pedicle, etc.), allowing anterolisthesis.

Type V: Pathologic—attenuation of the posterior elements, with subluxation, secondary to abnormal bone quality (e.g. osteogenesis imperfecta, neurofibromatosis, etc.).

Type VI: Postsurgical—anterolisthesis that occurs or worsens following compressive laminectomy.

degenerative changes in the disks and facet joints, allowing subluxation. It most commonly occurs at L4–L5 and is often associated with spinal stenosis. The most common type of spondylolisthesis is type II or isthmic spondylolisthesis; this is caused by a defect in the pars interarticularis at L5, resulting in slippage at L5–S1. The pars defect, referred to as spondylolysis, is believed to be a stress or fatigue fracture and occurs in most affected individuals when they are between the ages of 4 and 7. Spondylolysis is present in 5% to 6% of the normal adult population; 75% to 80% of these individuals also demonstrate spondylolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis is twice as common in males as in female and is more common in whites than in blacks. It is also seen more commonly in athletes who participate in sports demanding frequent hyperextension, such as gymnasts or football lineman.

In children and adolescents, spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis may present as back pain, frequently associated with hamstring spasm. Other less common causes of back pain in the pediatric population include disk space infection, benign tumors such as osteoid osteoma, or lumbar disk herniation. Isthmic spondylolisthesis can also be, and more commonly is, a cause of back pain in the adult. Patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis are reported to have an increased prevalence of disk degeneration, back pain, and sciatica, with the onset of symptoms occurring at any time during adulthood. Because back pain is such a ubiquitous complaint, the relationship between a patient’s complaint of back or leg pain and the presence of spondylolisthesis is often difficult to determine.

Evaluation of the patient with spondylolisthesis begins with a thorough history and physical. In the adult, a history of back pain during adolescence may be helpful. Although acute pars fractures are occasionally seen, there is usually no distinct history of trauma given. The patient typically presents

252 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

with low back pain, which radiates into the buttock, and on occasion, down the leg in a dermatomal distribution. Physical examination may demonstrate tenderness in the area of the L5–S1 facet joint. Often a characteristic, painful “catch” in extension is elicited. The most telltale sign in the adolescent is hamstring spasm, which can be quite severe. In patients with a high-grade slip, flattening of the buttocks and a transverse abdominal crease may be seen. Neurologic findings are rare, although in more advanced cases L5 findings may be seen.

Plain radiographs should be obtained in the standing position. Most pars defects are visible on the lateral radiograph. If the diagnosis is uncertain, oblique views increase the sensitivity of plain radiography. The posterior arch has been described as a “Scotty dog” on the oblique view, and a pars defect appears as a “collar” on the neck of the Scotty dog (Fig. 5-60). Radionuclide bone scanning [single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan] or fine-cut CT scanning may be used to diagnose occult defects in the pars interarticularis, and MRI imaging is useful to identify nerve root compression in the L5–S1 foramen in patients with significant leg pain.

4

5

W P

FIGURE 5-60. A pars defect (spondylolysis) at L4, seen on this oblique radiograph as a “collar” on the neck of the “Scotty dog.”

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

253 |

The treatment of patients with spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis depends on the degree of slippage as well as the patient’s symptoms. The percent slip ranges from 0% to 100% and has been broken down as grades I (0%–25%), II (25%–50%), III (50%–75%), and IV (75%–100%). It is not uncommon for pediatric patients to be diagnosed with spondylolisthesis following an episode of minor trauma and then to become asymptomatic. In the skeletally immature patient who is asymptomatic, activity guidelines are based on the degree of slippage. In patients with a grade I slip, full activity is allowed with annual radiographic follow-up. Skeletally immature individuals with grade II spondylolisthesis are advised to avoid contact sports or repetitive hyperextension activities such as are seen in gymnastics. Operative treatment is usually recommended for skeletally immature patients with progressive slippage or with grades III or IV spondylolisthesis.

Symptomatic patients are initially treated with activity modification and NSAIDs. Because many of these patients are athletes, temporarily holding them out of their sport frequently results in improvement in symptoms. The patient is then begun on a program of Williams’ flexion exercises and gradually increased activity. Persistent symptoms sometimes respond to bracing, and treatment with a brace or cast is advocated by some when an acute pars fracture is suspected. The majority of patients, both pediatric and adult, respond quite well to nonoperative treatment, although a return to high-level competitive sports is sometimes impossible.

Operative treatment is recommended for patients with progressive spondylolisthesis, for skeletally immature patients with spondylolisthesis exceeding 50%, and for patients with persistent, incapacitating pain. The overwhelming majority of surgical patients fall into the latter category. The hallmark of the surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis is spinal fusion. Intertransverse fusion between the transverse processes of L5 in the sacral alae, utilizing iliac crest bone graft, has a high rate of success with a low complication rate. In adult patients with significant buttock and leg pain, or in individuals with neurologic deficits secondary to root compression, removal of the loose posterior arch of L5 and decompression of the exiting L5 nerve root are recommended. Fusion is routinely performed in addition to decompression in these cases. Many authors recommend pedicle screw instrumentation as an adjunct to spinal fusion; instrumentation is routine in adults, in patients with spondylolisthesis greater than 25%, and in individuals with documented instability. Finally, operative reduction of the spondylolisthesis is advocated by some in cases of severe spondylolisthesis, usually exceeding 60% to 70% slippage, with a concomitant cosmetic deformity. The results of surgery are usually quite rewarding, particularly in the pediatric population. Complications of surgery include failure of fusion, progressive slippage, persistent or recurrent pain, and neurologic injury. Complication rates are higher in

254 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

adults, in higher grades of spondylolisthesis, and when reduction is attempted.

Suggested Readings

MacEwen GD. Pediatric Fractures. Malvern, PA: Williams & Wilkins, 1993. Staheli L. Fundamentals of Pediatric Orthopaedics. New York: Raven Press,

1992.

Wenger D, Rang M. Art and Practice of Children’s Orthopaedics. New York: Raven Press, 1993.

Questions

Note: Answers are provided at the end of the book before the index.

5-1. Skeletal dysplasias:

a.Are focal abnormalities of the skeleton

b.Are frequently hereditary

c.Rarely involve the craniofacial structures

d.Are typically due to a vitamin deficiency

e.Are not associated with angular deformity of the knees 5-2. Developmental dysplasia of the hip:

a.Is multifactorial in origin

b.Is more common in females

c.Usually involves the left hip

d.All of the above

e.None of the above

5-3. The periosteum:

a.Is osteogenic in the child

b.Usually blocks fracture reduction

c.Is of no mechanical significance

d.Is a cartilaginous membrane

e.Extends over the articular surface 5-4. The physis:

a.Is the strongest structure of a long bone

b.Has three zones

c.Is critical for growth in girth of the diaphysis

d.Is rarely fractured

e.Is the site of pathology in achondroplasia 5-5. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis:

a.Is more common in thin children

b.Usually is classified as stable versus unstable

c.Is often treated by femoral osteotomy

d.Causes an internal rotational deformity of the hip

e.Presents as a painless limp

5. Children’s Orthopedics |

255 |

5-6. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head can be seen in:

a.Perthes’ disease

b.Developmental dysplasia of the hip

c.Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

d.All of the above

e.None of the above

5-7. Which of the following is not typical of Down syndrome?

a.Trisomy 21

b.C1–C2 subluxation

c.Hip subluxation

d.Cavus (high arch) feet

e.Ligamentous laxity

5-8. Which of the following should not lead one to the diagnosis of battered child syndrome?

a.Parietal skull fractures

b.Humeral diaphyseal fracture

c.Femoral fracture in a nonambulatory child

d.Cigarette burns

e.Retinal hemorrhages

5-9. In the workup for growing pain, leukemia must be considered. Which of the following is not a characteristic of “growing pain syndrome?”

a.Nocturnal pain in the leg

b.Symmetrical involvement, although not simultaneous

c.Occurs in children 3 to 9 years of age

d.Normal white count

e.Metaphyseal banding on X-ray

5-10. Trendelenburg gait:

a.Results from weakness of the adductor muscles

b.Is not commonly caused by diseases of muscle weakness

c.Is characterized by the pelvis dropping on the contralateral side when weight is borne on the affected side

d.Follows lengthening of the lever arm at the hip

e.Is not a characteristic of DDH

5-11. Pediatric fractures are known to show extensive degrees of remodeling. This assumption can often be misleading. All the following deformities typically cause problems simply because they do not remodel adequately, except:

a.Rotational deformity

b.Angulation not in the phase of motion of the joint

c.Salter IV fractures of the physis

d.Plastic deformation of the ulna with fractured radius

e.Complete displacement in forearm fractures of a 4-year-old child

256 J.N. Delahay and W.C. Lauerman

5-12. The Pavlik harness:

a.Is the worldwide treatment for infants with DDH

b.Can cause avascular necrosis

c.Is not applicable for children over 1 year of age

d.All of the above

e.None of the above