SpeakingOilGas

.pdfPipelines

Pipelines are an important part of all phases of production, from the gathering systems joining wells to process facilities and in the distribution system delivering oil and gas to refineries and markets. Pipelines vary from simple steel tubes to state-of-the-art spiral-wound, flexible lines. They may vary in diameter from 50 millimetres to two metres.

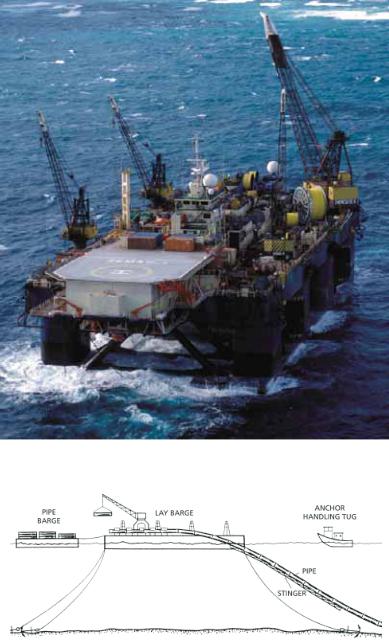

Laying of pipelines can be expensive, particularly offshore where sophisticated techniques are used to ensure the line is properly placed. The traditional approach offshore is to weld lengths of pipe together on a lay barge and progressively lower or slide the pipeline to its designated sea bed location. The pipe is guided and supported for a short distance after leaving the lay barge by a ramp called a stinger mounted at the stern of the vessel. It is possible to lay pipe in 1000 metres of water using these conventional techniques.

For deeper water, up to 2500 metres, a J-lay method is used whereby the pipe, still welded into a continuous length on the barge, is dropped vertically and then laid on the sea bed in a bowed incline (like the letter J). Lines of up to 700 millimetres diameter have been laid in very deep water with this technique using heavy lift/lay barges.

Other methods for shallower water include welding the pipe lengths together onshore and then pulling (or towing) the completed line into the desired location as one whole unit. For smaller (up to 150 millimetres diameter) lines, it is feasible to have the pipe delivered on a reel to a specially designed reel barge which then unrolls the line along the appointed route.

Onshore pipelines are also welded and laid in sections. Usually the onshore lines are buried, thus the laying operation is preceded by trench cutting and followed by burial.

86 |

SPEAKING OIL & GAS |

Pipe-laying operations from conventional lay barge, ‘Semac I’

Pipe-laying operations from conventional lay barge

EVALUATION & PRODUCTION |

87 |

Many offshore lines are also buried, especially in shallow water where currents and tides may cause scouring and movement if laid on top of the sea bed. Sometimes, if not buried, the lines are given thick outer coatings of concrete to weigh them down. However, there is no need for weight coating in very deep water as the currents are less and the increased thickness of the steel needed to withstand the higher external pressures at depth adds sufficient weight to keep them in place.

Petroleum pipelines are also coated with several layers of protective material and fitted with cathodic protection devices that inhibit corrosion. Internal pipe maintenance and cleaning is conducted by sending a scrubbing device or pig (originally named because of the squealing noise early versions made as they traversed the line) through the pipeline at regular time intervals. Other, more sophisticated pigs are able to inspect the integrity of welds and the internal condition of the pipe as they move along.

Some pipelines, particularly from offshore oil and gas fields to shore production facilities, carry oil, gas and condensate together. This is known as multi-phase flow. At the shore end of the line a device called a slug catcher (a series of parallel horizontal pipes) slows down the flow and enables the liquid (oil and condensate) ‘slugs’ to be separated from the gas.

Remote operating vehicles

Beyond diver depths of 200 metres, major enabling technical advances in subsea work are typified by the use of remote operated vehicles (ROVs). ROVs and remote tooling systems can be operated long distances from the mother ship or control point. This enables subsea construction work, such as connection of pipelines and production systems, to take place in very deep water. The ROVs are operated from the surface, usually via an umbilical. Cameras fitted to their hulls enable the operator to guide the vehicles into position and then send signals to the mechanical arms to perform the given task. In recent times, digital systems and the use of megapixel chips have revolutionised the visibility of the onboard cameras.

88 |

SPEAKING OIL & GAS |

In addition, capabilities of these vehicles developed for the military have been made more generally available and the offshore petroleum industry is developing autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). These are untethered, free-ranging vehicles that can be programmed to do a task, such as a grid pattern sea bed survey or a complete pipeline survey, and then be picked up later once the job has been completed. There is no longer any need to tow the vehicle during a survey, thus saving time which can be devoted to other work.

Coal Seam Methane

Coal seam methane (CSM, sometimes called coal bed methane or coal seam gas) is natural gas formed as part of the geological process of changing organic matter into coal. The CSM is generated either from a biological process resulting from microbial action or from a thermal process resulting from increased heat with the depth of burial of the coal seams.

Unlike conventional natural gas reservoirs, where the gas is trapped in the pore spaces within rocks like sandstone and limestone, the methane trapped in coal is adsorbed onto the surface of cleats or joints in the coal and held in place by the pressure of water within the seam. Thus coal is both the source and the reservoir for CSM.

The surface area of the cleats is very large, so coal can potentially contain more methane per unit volume than many conventional gas reservoirs. The amount of trapped gas is related to the coal type and the pressure and temperature of burial. However most coals have lower permeabilities than conventional gas reservoirs and the production rates are lower, often requiring some form of stimulation such as hydraulic fracturing.

This is achieved by drilling wells into the coal seam and pumping down large volumes of water and sand to produce new fractures and/or force open and extend the existing cleats and joints. Generally the fracturing extends for up to several hundred metres in all directions from the well bore. The sand helps to keep the fractures open.

EVALUATION & PRODUCTION |

89 |

However the gas trapped on the coal surfaces cannot be released until the water pressure holding it there is decreased. This is done by physically pumping water from the wells until gas comes free and begins to flow naturally up the wells. The time taken for gas to begin flowing after starting the pumps can vary from several weeks to several months. The water can be re-injected into formations below the coal seams, or collected in dams at the surface where it is allowed to evaporate. Research is also being conducted into the potential for using the water for agriculture and other purposes.

CSM is typically found at shallower depths than conventional gas (200 metres –1000 metres compared to 1500 metres –4000 metres plus) and reaches the surface at very low pressure. It must be compressed before being sent through pipelines to market. Nevertheless, the shallower depths do enable the use of small truck-mounted rigs to drill the wells which improves the economics of an operation.

Wells are generally drilled in groups of five — one central well and four surrounding it — called a ‘five spot’. The four outer wells are designed to drain water away from the central well which can then flow gas to surface. Development of a CSM field progresses when the four outer wells are themselves surrounded by newly drilled wells pumping water until the four also become producers and so on. A CSM field can contain hundreds of wells during its lifetime.

Not all parts of a coal seam are conducive to CSM production and explorers concentrate on ‘sweet spots’ — areas that have the highest degree of natural fractures. These can be detected using the same geophysical techniques employed in conventional petroleum exploration. Sometimes a CSM operation is employed in advance of underground coal mining, the extraction of the gas lessening the risk of explosion during the mining operation.

CSM has become an important source of natural gas in the USA where it supplies about eight per cent of the nation’s gas demand. In Australia, CSM is being produced in the Sydney Basin of New South Wales and in the Bowen and Surat Basins of Queensland. The Queensland CSM flow supplies 30 per cent of the State’s gas demand.

90 |

SPEAKING OIL & GAS |

Chapter 5. PERMITS

The ownership of oil and gas resources is usually vested in the government of the country concerned, although a notable exception is the onshore USA where the landholder holds the rights. In fact, in the USA, the landowner can bequeath and/or sell all or a portion of these rights to other parties. Over time this can lead to a complicated ownership structure, even to the extent that there might be different owners to the petroleum rights in a vertical sense — in other words, one individual or group of people may own the rights from the surface down to, say, 1500 metres while another group may own the deeper rights.

Any oil company wishing to explore for petroleum must make a contract or agreement with the owners or their representatives before exploration can begin. The contract regulates the relationship, and the rights and obligations of the parties to it. Contracts can be forged between oil companies and host governments, between oil companies and national petroleum or energy companies representing host governments and (in onshore USA) between oil companies and the private owners of the petroleum rights. Additional agreements are made between oil company partners, one of which is elected operator of the joint venture.

PERMITS |

91 |

The overriding role of government today is to regulate to provide a level playing field (tempered, however, in countries that want to promote their own national oil companies) as well as to set out rules for safe operation and care of the environment in which the companies work.

Evolution of permit agreements

The traditional arrangement is a concession or lease agreement. Historically this was an arrangement whereby an oil company was given exclusive permission by a government to explore a large portion of a country over a long period of time in return for an agreed percentage of any oil production that resulted. Often the country concerned had no infrastructure or expertise and lacked finances, thus the company came in and provided all these necessities. There are few concession arrangements with governments of developing nations left today. Those that exist usually include provisions for government participation, a good example is that between Royal Dutch Shell and the Government of Brunei Darussalam.

Changes to this system began in Russia with the revolution of 1917 when the Soviets nationalised their industry. In 1938 Mexico did the same thing. Following World War II the world rapidly moved from coal-driven to oil-driven industry which naturally increased the demand for oil. This in turn led to more exploration and production activity, more competition and a marked change in the dynamics between the oil companies and the host countries. As the host countries gained more bargaining power they began to demand an increased share of the profits.

Venezuela introduced a 50:50 share split in 1948, although it retained the basic form of the concession agreement. Saudi Arabia did the same in 1950 and other Middle East countries followed suit.

In 1952 Iranian leader Mossadeque nationalised the country’s petroleum industry. Mossadeque was then toppled by a coup which brought the Shah to power. The Shah retained the nationalisation, but introduced the idea of international oil companies forming joint ventures with the government. Italian company AGIP was the first to form this alliance.

92 |

SPEAKING OIL & GAS |

In 1960 Indonesia took the industry on a new turn when it introduced the concept of a Production Sharing Contract (PSC). Essentially this is a system where a contractor (international oil company) is exclusively appointed to conduct petroleum operations within a specific contract area for a specific period, but under stringent conditions and strict supervision. The company carries all the financial risks, provides capital expenditure, personnel and expertise. It also deals directly with the national petroleum company which takes a high percentage of any production. The international company is allowed to recover costs from production, but often pays royalties before it can make any profits via its percentage of production agreed with the national company. The PSC system is now widely used for petroleum permits around the world, including countries in South East Asia, Africa and South America.

Further inroads into the former international oil company dominance came in 1969 when Libya broke the 50:50 split by imposing a 50 per cent tax to the companies’ half share of production. In effect companies working in Libya received only 23 per cent of the oil they produced.

The oil crises of the 1970s introduced the concept in Middle East countries of exacting a 20 per cent royalty plus a tax of 85 per cent on all production and added the clause that there would be mandatory participation by the relevant national petroleum company in each production concession. This system is still widely used throughout the Middle East.

Today, most petroleum permit systems are based on the production sharing contract or the concession agreement. The overriding point is that nationalism plays a key role in both.

Permit variations

Concessions versus PSCs

Essentially the principles of PSCs and concession agreements are similar. The oil companies (contractors in PSCs or licensees in Concessions) have an exclusive right to explore for and produce hydrocarbons from a given area over a given period of time. In addition, the oil companies carry all

PERMITS |

93 |

the financial risks and supply all the expertise, personnel and capital expenditure. Both systems also incorporate the obligation to submit work programs, progress reports (including all geological and geophysical data, test results etc) and budgets for approval.

However there are differences between the two systems. Some of the main ones are:

•In a PSC, oil companies deal with the national petroleum company, while in a Concession they deal with the host government.

•In a PSC, oil companies agree, and are subject to, a production split after being allowed to recover costs from initial production. In a Concession the companies can take all the petroleum produced, but they must pay a royalty based on a percentage of production. (Royalties are sometimes incorporated in a PSC arrangement as well).

•In a PSC, oil companies may be asked to market the national oil company’s share of production.

•In a PSC the oil companies are subject to regular audits.

•In a PSC the title to assets (including equipment and production outlets) are transferred to the national petroleum company when costs are recovered. In a Concession the title to assets are returned to the host government at no cost upon termination of the permit.

The fiscal regimes vary between both systems and between individual countries using the same system. A general principle has been to have a taxation level that is generous to oil companies when a country has untried potential and wishes to entice exploration. When that potential is proven with discoveries, oil companies wanting to join the hunt are subjected to a more onerous taxation level. The country then returns to a generous tax regime when its petroleum province has matured and the government wants to entice companies to look at less prospective or frontier areas.

94 |

SPEAKING OIL & GAS |

Risk Sharing Contracts

This is a variation on the PSC which combines a contractor-type service agreement with provision for the contractor to supply risk capital for a share of the rewards. The contractor (oil company) has no ownership rights to the petroleum produced, but will be paid either in cash or sometimes in a volume of oil to the same value in lieu of cash. If the latter payment is used, the value is capped — in other words, the oil company is unable to benefit from any rise in oil price on world markets.

Although such a deal is onerous, oil companies enter the arrangement to get access to crude supplies for refineries they have already operating in that country. The arrangement may include a deal whereby the national petroleum company supplies feedstock to the refinery.

Risk sharing contracts are used in Argentina, Peru, Venezuela, Brazil and Ecuador.

Technical Service Agreements

This is an arrangement whereby the international oil company does not supply any risk capital, but does provide technical services and sometimes training for a country’s nationals. The company’s payment is on a cost plus basis unrelated to the success of the venture. Usually it is a flat fee related to production and the arrangement may also include the right to buy production.

Companies enter such agreements in places where the production volumes are large and where they can obtain marketing rights for the downstream end of the operation.

Technical service agreements are in place in Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi, Mexico, Argentina, Iran and Venezuela.

PERMITS |

95 |