- •Contents

- •Preface to the first edition

- •Flagella

- •Cell walls and mucilages

- •Plastids

- •Mitochondria and peroxisomes

- •Division of chloroplasts and mitochondria

- •Storage products

- •Contractile vacuoles

- •Nutrition

- •Gene sequencing and algal systematics

- •Classification

- •Algae and the fossil record

- •REFERENCES

- •CYANOPHYCEAE

- •Morphology

- •Cell wall and gliding

- •Pili and twitching

- •Sheaths

- •Protoplasmic structure

- •Gas vacuoles

- •Pigments and photosynthesis

- •Akinetes

- •Heterocysts

- •Nitrogen fixation

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Growth and metabolism

- •Lack of feedback control of enzyme biosynthesis

- •Symbiosis

- •Extracellular associations

- •Ecology of cyanobacteria

- •Freshwater environment

- •Terrestrial environment

- •Adaption to silting and salinity

- •Cyanotoxins

- •Cyanobacteria and the quality of drinking water

- •Utilization of cyanobacteria as food

- •Cyanophages

- •Secretion of antibiotics and siderophores

- •Calcium carbonate deposition and fossil record

- •Chroococcales

- •Classification

- •Oscillatoriales

- •Nostocales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •RHODOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Pit connections

- •Calcification

- •Secretory cells

- •Iridescence

- •Epiphytes and parasites

- •Defense mechanisms of the red algae

- •Commercial utilization of red algal mucilages

- •Reproductive structures

- •Carpogonium

- •Spermatium

- •Fertilization

- •Meiosporangia and meiospores

- •Asexual spores

- •Spore motility

- •Classification

- •Cyanidiales

- •Porphyridiales

- •Bangiales

- •Acrochaetiales

- •Batrachospermales

- •Nemaliales

- •Corallinales

- •Gelidiales

- •Gracilariales

- •Ceramiales

- •REFERENCES

- •Cell structure

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Classification

- •Position of flagella in cells

- •Flagellar roots

- •Multilayered structure

- •Occurrence of scales or a wall on the motile cells

- •Cell division

- •Superoxide dismutase

- •Prasinophyceae

- •Charophyceae

- •Classification

- •Klebsormidiales

- •Zygnematales

- •Coleochaetales

- •Charales

- •Ulvophyceae

- •Classification

- •Ulotrichales

- •Ulvales

- •Cladophorales

- •Dasycladales

- •Caulerpales

- •Siphonocladales

- •Chlorophyceae

- •Classification

- •Volvocales

- •Tetrasporales

- •Prasiolales

- •Chlorellales

- •Trebouxiales

- •Sphaeropleales

- •Chlorosarcinales

- •Chaetophorales

- •Oedogoniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •EUGLENOPHYCEAE

- •Nucleus and nuclear division

- •Eyespot, paraflagellar swelling, and phototaxis

- •Muciferous bodies and extracellular structures

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Nutrition

- •Classification

- •Heteronematales

- •Eutreptiales

- •Euglenales

- •REFERENCES

- •DINOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Theca

- •Scales

- •Flagella

- •Pusule

- •Chloroplasts and pigments

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Nucleus

- •Projectiles

- •Accumulation body

- •Resting spores or cysts or hypnospores and fossil Dinophyceae

- •Toxins

- •Dinoflagellates and oil and coal deposits

- •Bioluminescence

- •Rhythms

- •Heterotrophic dinoflagellates

- •Direct engulfment of prey

- •Peduncle feeding

- •Symbiotic dinoflagellates

- •Classification

- •Prorocentrales

- •Dinophysiales

- •Peridiniales

- •Gymnodiniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •Chlorarachniophyta

- •REFERENCES

- •CRYPTOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Ecology

- •Symbiotic associations

- •Classification

- •Goniomonadales

- •Cryptomonadales

- •Chroomonadales

- •REFERENCES

- •CHRYSOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Internal organelles

- •Extracellular deposits

- •Statospores

- •Nutrition

- •Ecology

- •Classification

- •Chromulinales

- •Parmales

- •Chrysomeridales

- •REFERENCES

- •SYNUROPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •REFERENCES

- •EUSTIGMATOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PINGUIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •DICTYOCHOPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •Rhizochromulinales

- •Pedinellales

- •Dictyocales

- •REFERENCES

- •PELAGOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •BOLIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCE

- •BACILLARIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Cell division and the formation of the new wall

- •Extracellular mucilage, biolfouling, and gliding

- •Motility

- •Plastids and storage products

- •Resting spores and resting cells

- •Auxospores

- •Rhythmic phenomena

- •Physiology

- •Chemical defense against predation

- •Ecology

- •Marine environment

- •Freshwater environment

- •Fossil diatoms

- •Classification

- •Biddulphiales

- •Bacillariales

- •REFERENCES

- •RAPHIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •XANTHOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Chloroplasts and food reserves

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Mischococcales

- •Tribonematales

- •Botrydiales

- •Vaucheriales

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOTHAMNIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Chloroplasts and photosynthesis

- •Phlorotannins and physodes

- •Life history

- •Classification

- •Dictyotales

- •Sphacelariales

- •Cutleriales

- •Desmarestiales

- •Ectocarpales

- •Laminariales

- •Fucales

- •REFERENCES

- •PRYMNESIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella

- •Haptonema

- •Chloroplasts

- •Other cytoplasmic structures

- •Scales and coccoliths

- •Toxins

- •Classification

- •Prymnesiales

- •Pavlovales

- •REFERENCES

- •Toxic algae

- •Toxic algae and the end-Permian extinction

- •Cooling of the Earth, cloud condensation nuclei, and DMSP

- •Chemical defense mechanisms of algae

- •The Antarctic and Southern Ocean

- •The grand experiment

- •Antarctic lakes as a model for life on the planet Mars or Jupiter’s moon Europa

- •Ultraviolet radiation, the ozone hole, and sunscreens produced by algae

- •Hydrogen fuel cells and hydrogen gas production by algae

- •REFERENCES

- •Glossary

- •Index

364 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF TWO MEMBRANES

cells, which are probably a form of resting cell. All of the cells are of the same ploidy level and sexual reproduction is not known.

The silicoflagellates originated in the Cretaceous, with the earlier forms having a simpler skeleton than those existing today. Fossils of silicoflagellates are common in calcareous chalks along with members of the Prymnesiophyceae. Silicoflagellates constitute a prominent part of the phytoplankton in the colder seas of today.

REFERENCES

Belcher, J. H., and Swale, E. M. F. (1971). The microanatomy of Phaeaster pascheri Scherffel (Chrysophyceae). Br. Phycol. J. 6:157–69.

Cavalier-Smith, T., Chao, E. E., and Allsopp, T. E. P. (1995). Ribosomal RNA evidence for chloroplast loss within Heterokonta: pedinellid relationships and a revised classification of ochristan algae. Arch. Protistenkd. 145:209–20.

Daugbjerg, N. (1996). Mesopedinella arctica gen. et sp. nov. (Pedinelles, Dictyochophyceae). I. Fine structure of a new marine phytoflagellate from Arctic Canada.

Phycologia 35:435–45.

Daugbjerg, N., and Andersen, R. A. (1997). A molecular phylogeny of heterokont algae based on analyses of chloroplast-encoded rbcL sequence data. J. Phycol.

33:1031–41.

Daugbjerg, N., and Henriksen, P. (2001). Pigment composition and rbcL sequence data from the silicoflagellate Dictyocha speculum: a heterokont alga with pigments similar to some haptophytes. J. Phycol. 37:1110–20.

Henriksen, P., Knipschildt, F., Moestrup, Ø., and Thomsen, H. A. (1993). Autecology, life history and toxicology of the silicoflagellate Dictyocha speculum (Silicoflagellata, Dictyochophyceae). Phycologia 32:29–39.

Hibberd, D. J. (1971). Observations on the cytology and ultrastructure of Chrysoamoeba radians Klebs (Chrysophyceae). Br. Phycol. J. 6:207–23.

Hibberd, D. J., and Chretiennot-Dinet, M.-J. (1979). The ultrastructure and taxonomy of Rhizochromulina marina gen. et sp. nov., an amoeboid marine chrysophyte. J. Mar. Biol. Assn., UK 59:179–93.

Koutoulis, A., McFadden, G. I., and Wetherbee, R. (1988). Spine-scale reorientation in Apedinella radians (Pedinelles, Chrysophyceae): the microarchitecture and immunocytochemistry of the associated cytoskeleton. Protoplasma

147:25–41.

Moestrup, Ø. (1995). Current status of chrysophyte ‘splinter groups’: synurophytes, pedinellids, silicoflagellates. In Chrysophyte Algae, ed. C. D. Sandgren, J. R. Smol, and J. Kristiansen, pp. 75–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Preisig, H. R. (1995). A modern concept of chrysophyte classification. In Chrysophyte Algae, ed. C. D. Sandgren, J. R. Smol, and J. Kristiansen, pp. 46–74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sekiguchi, H., Moriya, M., Nakayama, T., and Inouye, I. (2002). Vestigial chloroplasts in heterotrophic stramenopiles Pteridomonas danica and Ciliophrys infusionum (Dictyochophyceae). Protist

153:157–67.

Sekiguchi, H., Kawachi, M., Nakayama, T., and Inouye, I. (2003). A taxonomic re-evaluation of the Pedinellales (Dictyophyceae) based on morphological, behavioural and molecular data. Phycologia 42:165–82.

Swale, E. M. F. (1969). A study of the nanoplankton flagellate Pedinella hexacostata Vysotshiıˇ by light and electron microscopy. Br. Phycol. J. 4:65–86.

Throndsen, J. (1971). Apedinella gen. nov. and the fine structure of A. spinifera (Throndsen) comb. nov. Norw. J. Bot. 18:47–64.

van Valkenburg, S. D. (1971a). Observations on the fine structure of Dictyocha fibula Ehrenberg. I. The skeleton. J. Phycol. 7:113–18.

van Valkenburg (1971b). Observations on the fine structure of Dictyocha fibula Ehrenberg. II. The protoplast. J. Phycol. 7:118–32.

Chapter 15

Heterokontophyta

PELAGOPHYCEAE

The Pelagophyceae are a group of basically unicellular algae that are cytologically similar to the Chrysophyceae, in which they were previously classified (Andersen et al., 1993). The cells are very small (3–5 m) members of the ultraplankton and appear as small spheres with indistinct protoplasm under the light microscope. Recent studies on the sequences of small-subunit RNA nucleotides in these algae have shown them to be closely related to each other and distinct from other members of the Heterokontophyta (Saunders et al., 1997). While these algae have been shown to be distinct from other members of the Heterokontophyta based on molecular data, they do not have cytological or morphological characters which are very different from other members of the phylum.

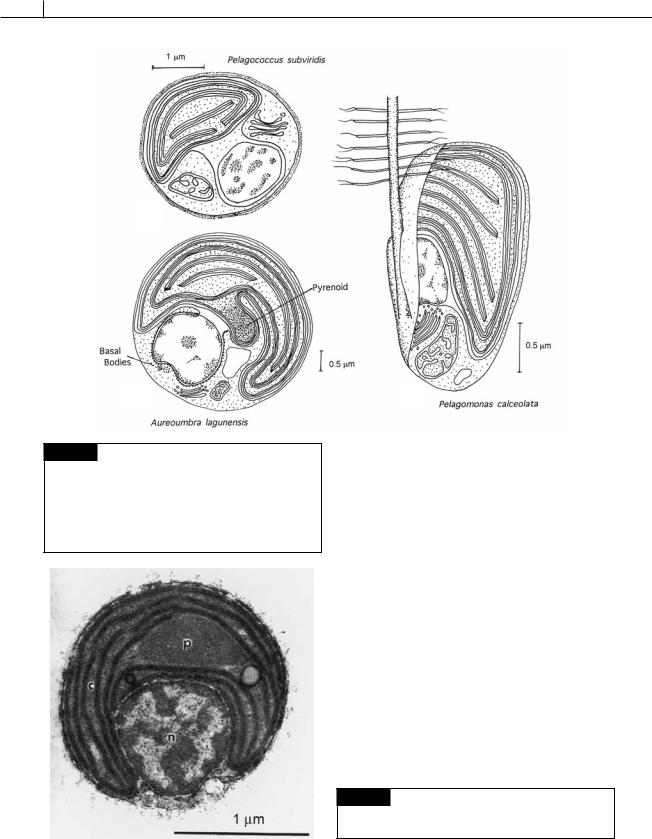

Pelagomonas calceolata is a very small (1.5 m

3 m) ultraplanktonic marine alga with a single tinsel flagellum and basal body, and a single chloroplast and mitochondrion (Fig. 15.1(c)) (Andersen et al., 1993). Another member of the marine ultraplankton is Pelagococcus subviridis, a green-gold spherical non-motile cell (2.5–3.0 m) with a single chloroplast, mitochondrion, and nucleus (Fig. 15.1(a)) (Vesk and Jeffery, 1987).

Members of the class are economically important because some of the algae produce “brown tides.” Aureoumbra lagunensis (Fig. 15.1(b)) is the causative agent of brown tides in Texas (DeYoe

et al., 1997), while Aureococcus anophagefferens forms brown tides along the coasts of New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. The numbers of cells in brown tides can be so large that they can exclude light from the benthic eelgrass (Zostera marine), resulting in elimination of the eelgrass. The larvae of the bay scallop feed off eelgrass and the bay scallop industry was virtually wiped out for a number of years after a brown tide in the waters off the northeast United States (Nicholls, 1995).

Aureoumbra lagunensis (Fig. 15.1(b)) is able to grow at its maximum rate at salinities as high as 70 PSU (practical salinity units; seawater is about 35 PSU). Few algae are able to survive these hypersaline conditions. In addition, the surface of the cells are covered with a slime layer that reduces predation (Liu and Buskey, 2000). A combination of these advantages enables A. lagunensis to outcompete other algae.

Aureococcus anophagefferens (Fig. 15.2) is a psychrophilic alga that is able to grow at low temperatures and survive extended periods of darkness. This explains its ability to form algal blooms (Popels and Hutchins, 2002). Dense cell populations of 100 000 cells ml 1 were recorded before the ice formed in Great Bay, Long Island, New York. Two months later, after the ice had melted the cell populations were still as high as 60 000 cells ml 1, concentrations that still were at bloom levels (Gobler et al., 2002). It has been shown that filter feeders grow at a reduced rate when cells of Aureococcus are present (Greenfield et al., 2004).

366 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF TWO MEMBRANES

(a)

(b)

Fig. 15.1 (a) Pelagococcus subviridis showing the single chloroplast, nucleus, and mitochondrion. (b) Aureoumbra lagunensis with the characteristic stalked pyrenoid and two basal bodies near the nucleus. (c) Pelagomonas calceolata showing the single flagellum fitting into a groove in the cell. ((a) adapted from Vesk and Jeffery, 1987; (b) adapted from DeYoe et al., 1997; (c) adapted from Andersen et al., 1993.)

(c)

REFERENCES

Andersen, R. A., Saunders, G. W., Paskind, M. P., and Sexton, J. P. (1993). Ultrastructure and 18S rRNA gene sequence for Pelagomonas calceolata gen. et sp. nov. and the description of a new algal class, the Pelagophyceae classis nov. J. Phycol. 29:701–15.

DeYoe, H. R., Stockwell, D. A., Bidigare, R. R., Latasa, M., Johson, P. W., Hargraves, P. E., and Suttle, C. A. (1997). Description and characterization of the algal species Aureoumbra lagunensis gen. at sp. nov. and referral of

Aureoumbra and Aureococcus to the Pelagophyceae. J. Phycol. 33:1042–8.

Gobler, C. J., Renaghan, M. J., and Buck, N. J. (2002). Impacts of nutrients and grazing mortality on the abundance of Aureococcus anophagefferens during a New York brown tide bloom. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:129–41.

Greenfield, D. I., Lonsdale, D. J., Cerrato, R. M., and Lopez, G. R. (2004). Effects of background

Fig. 15.2 Transmission electron micrograph of a section of a cell of Aureococcus anophagefferens. (c) Chloroplast;

(n) nucleus; (p) pyrenoid. (From Sieburth et al., 1988.)

HETEROKONTOPHYTA, PELAGOPHYCEAE |

367 |

|

|

concentrations of Aureococcus anophagefferens (brown tide) on growth and feeding in the bivalve Mercenaria mercenaria. Mar. Biol. Progr. Ser. 274:171–81.

Liu, H., and Buskey, E. J. (2000). The exopolymer secretions (EPS) layer surrounding Aureoumbra lagunensis cells affects growth, grazing, and behavior of protozoa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:1187–91.

Nicholls, K. H. (1995). Chrysophyte blooms in the plankton and neuston of marine and freshwater systems. In Chrysophyte Algae, Ecology, Phylogeny and Development, ed. C. D. Sandgren, J. P. Smol, and J. Kristiansen, pp. 181–213. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Popels, L. C., and Hutchins, D. A. (2002). Factors affecting dark survival of the brown tide alga Aureococcus anophagefferens (Pelagophyceae). J. Phycol. 38:738–44.

Saunders, G. W., Potter, D., and Andersen, R. A. (1997). Phylogenetic affinities of the Sarcinochrysidales and Chrysomeridales (Heterokonta) based on analysis of molecular and combined data. J. Phycol. 33:310–18.

Sieburth, J. M., Johnson, P. W., and Hargraves, P. E. (1988). Ultrastructure and ecology of Aureococcus anophagefferens gen. et sp. nov. (Chrysophyceae): the dominant picoplankter during a bloom in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, summer 1985. J. Phycol. 24:416–25.

Vesk, M., and Jeffrey, S. W. (1987). Ultrastructure and pigments of two strains of the picoplanktonic alga

Pelagococcus subviridis (Chrysophyceae). J. Phycol. 23:322–36.