- •Table of Contents

- •Preface

- •What is ASP.NET?

- •Installing the Required Software

- •Installing the Web Server

- •Installing Internet Information Services (IIS)

- •Installing Cassini

- •Installing the .NET Framework and the SDK

- •Installing the .NET Framework

- •Installing the SDK

- •Configuring the Web Server

- •Configuring IIS

- •Configuring Cassini

- •Where do I Put my Files?

- •Using localhost

- •Virtual Directories

- •Using Cassini

- •Installing SQL Server 2005 Express Edition

- •Installing SQL Server Management Studio Express

- •Installing Visual Web Developer 2005

- •Writing your First ASP.NET Page

- •Getting Help

- •Summary

- •ASP.NET Basics

- •ASP.NET Page Structure

- •Directives

- •Code Declaration Blocks

- •Comments in VB and C# Code

- •Code Render Blocks

- •ASP.NET Server Controls

- •Server-side Comments

- •Literal Text and HTML Tags

- •View State

- •Working with Directives

- •ASP.NET Languages

- •Visual Basic

- •Summary

- •VB and C# Programming Basics

- •Programming Basics

- •Control Events and Subroutines

- •Page Events

- •Variables and Variable Declaration

- •Arrays

- •Functions

- •Operators

- •Breaking Long Lines of Code

- •Conditional Logic

- •Loops

- •Object Oriented Programming Concepts

- •Objects and Classes

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Classes

- •Constructors

- •Scope

- •Events

- •Understanding Inheritance

- •Objects In .NET

- •Namespaces

- •Using Code-behind Files

- •Summary

- •Constructing ASP.NET Web Pages

- •Web Forms

- •HTML Server Controls

- •Using the HTML Server Controls

- •Web Server Controls

- •Standard Web Server Controls

- •Label

- •Literal

- •TextBox

- •HiddenField

- •Button

- •ImageButton

- •LinkButton

- •HyperLink

- •CheckBox

- •RadioButton

- •Image

- •ImageMap

- •PlaceHolder

- •Panel

- •List Controls

- •DropDownList

- •ListBox

- •RadioButtonList

- •CheckBoxList

- •BulletedList

- •Advanced Controls

- •Calendar

- •AdRotator

- •TreeView

- •SiteMapPath

- •Menu

- •MultiView

- •Wizard

- •FileUpload

- •Web User Controls

- •Creating a Web User Control

- •Using the Web User Control

- •Master Pages

- •Using Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)

- •Types of Styles and Style Sheets

- •Style Properties

- •The CssClass Property

- •Summary

- •Building Web Applications

- •Introducing the Dorknozzle Project

- •Using Visual Web Developer

- •Meeting the Features

- •The Solution Explorer

- •The Web Forms Designer

- •The Code Editor

- •IntelliSense

- •The Toolbox

- •The Properties Window

- •Executing your Project

- •Using Visual Web Developer’s Built-in Web Server

- •Using IIS

- •Using IIS with Visual Web Developer

- •Core Web Application Features

- •Web.config

- •Global.asax

- •Using Application State

- •Working with User Sessions

- •Using the Cache Object

- •Using Cookies

- •Starting the Dorknozzle Project

- •Preparing the Sitemap

- •Using Themes, Skins, and Styles

- •Creating a New Theme Folder

- •Creating a New Style Sheet

- •Styling Web Server Controls

- •Adding a Skin

- •Applying the Theme

- •Building the Master Page

- •Using the Master Page

- •Extending Dorknozzle

- •Debugging and Error Handling

- •Debugging with Visual Web Developer

- •Other Kinds of Errors

- •Custom Errors

- •Handling Exceptions Locally

- •Summary

- •Using the Validation Controls

- •Enforcing Validation on the Server

- •Using Validation Controls

- •RequiredFieldValidator

- •CompareValidator

- •RangeValidator

- •ValidationSummary

- •RegularExpressionValidator

- •Some Useful Regular Expressions

- •CustomValidator

- •Validation Groups

- •Updating Dorknozzle

- •Summary

- •What is a Database?

- •Creating your First Database

- •Creating a New Database Using Visual Web Developer

- •Creating Database Tables

- •Data Types

- •Column Properties

- •Primary Keys

- •Creating the Employees Table

- •Creating the Remaining Tables

- •Executing SQL Scripts

- •Populating the Data Tables

- •Relational Database Design Concepts

- •Foreign Keys

- •Using Database Diagrams

- •Diagrams and Table Relationships

- •One-to-one Relationships

- •One-to-many Relationships

- •Many-to-many Relationships

- •Summary

- •Speaking SQL

- •Reading Data from a Single Table

- •Using the SELECT Statement

- •Selecting Certain Fields

- •Selecting Unique Data with DISTINCT

- •Row Filtering with WHERE

- •Selecting Ranges of Values with BETWEEN

- •Matching Patterns with LIKE

- •Using the IN Operator

- •Sorting Results Using ORDER BY

- •Limiting the Number of Results with TOP

- •Reading Data from Multiple Tables

- •Subqueries

- •Table Joins

- •Expressions and Operators

- •Transact-SQL Functions

- •Arithmetic Functions

- •String Functions

- •Date and Time Functions

- •Working with Groups of Values

- •The COUNT Function

- •Grouping Records Using GROUP BY

- •Filtering Groups Using HAVING

- •The SUM, AVG, MIN, and MAX Functions

- •Updating Existing Data

- •The INSERT Statement

- •The UPDATE Statement

- •The DELETE Statement

- •Stored Procedures

- •Summary

- •Introducing ADO.NET

- •Importing the SqlClient Namespace

- •Defining the Database Connection

- •Preparing the Command

- •Executing the Command

- •Setting up Database Authentication

- •Reading the Data

- •Using Parameters with Queries

- •Bulletproofing Data Access Code

- •Using the Repeater Control

- •More Data Binding

- •Inserting Records

- •Updating Records

- •Deleting Records

- •Using Stored Procedures

- •Summary

- •DataList Basics

- •Handling DataList Events

- •Editing DataList Items and Using Templates

- •DataList and Visual Web Developer

- •Styling the DataList

- •Summary

- •Using the GridView Control

- •Customizing the GridView Columns

- •Styling the GridView with Templates, Skins, and CSS

- •Selecting Grid Records

- •Using the DetailsView Control

- •Styling the DetailsView

- •GridView and DetailsView Events

- •Entering Edit Mode

- •Using Templates

- •Updating DetailsView Records

- •Summary

- •Advanced Data Access

- •Using Data Source Controls

- •Binding the GridView to a SqlDataSource

- •Binding the DetailsView to a SqlDataSource

- •Displaying Lists in DetailsView

- •More on SqlDataSource

- •Working with Data Sets and Data Tables

- •What is a Data Set Made From?

- •Binding DataSets to Controls

- •Implementing Paging

- •Storing Data Sets in View State

- •Implementing Sorting

- •Filtering Data

- •Updating a Database from a Modified DataSet

- •Summary

- •Security and User Authentication

- •Basic Security Guidelines

- •Securing ASP.NET 2.0 Applications

- •Working with Forms Authentication

- •Authenticating Users

- •Working with Hard-coded User Accounts

- •Configuring Forms Authentication

- •Configuring Forms Authorization

- •Storing Users in Web.config

- •Hashing Passwords

- •Logging Users Out

- •ASP.NET 2.0 Memberships and Roles

- •Creating the Membership Data Structures

- •Using your Database to Store Membership Data

- •Using the ASP.NET Web Site Configuration Tool

- •Creating Users and Roles

- •Changing Password Strength Requirements

- •Securing your Web Application

- •Using the ASP.NET Login Controls

- •Authenticating Users

- •Customizing User Display

- •Summary

- •Working with Files and Email

- •Writing and Reading Text Files

- •Setting Up Security

- •Writing Content to a Text File

- •Reading Content from a Text File

- •Accessing Directories and Directory Information

- •Working with Directory and File Paths

- •Uploading Files

- •Sending Email with ASP.NET

- •Configuring the SMTP Server

- •Sending a Test Email

- •Creating the Company Newsletter Page

- •Summary

- •The WebControl Class

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Standard Web Controls

- •AdRotator

- •Properties

- •Events

- •BulletedList

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Button

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Calendar

- •Properties

- •Events

- •CheckBox

- •Properties

- •Events

- •CheckBoxList

- •Properties

- •Events

- •DropDownList

- •Properties

- •Events

- •FileUpload

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •HiddenField

- •Properties

- •HyperLink

- •Properties

- •Image

- •Properties

- •ImageButton

- •Properties

- •Events

- •ImageMap

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Label

- •Properties

- •LinkButton

- •Properties

- •Events

- •ListBox

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Literal

- •Properties

- •MultiView

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Events

- •Panel

- •Properties

- •PlaceHolder

- •Properties

- •RadioButton

- •Properties

- •Events

- •RadioButtonList

- •Properties

- •Events

- •TextBox

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Properties

- •Validation Controls

- •CompareValidator

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •CustomValidator

- •Methods

- •Events

- •RangeValidator

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •RegularExpressionValidator

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •RequiredFieldValidator

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •ValidationSummary

- •Properties

- •Navigation Web Controls

- •SiteMapPath

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Events

- •Menu

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Events

- •TreeView

- •Properties

- •Methods

- •Events

- •HTML Server Controls

- •HtmlAnchor Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlButton Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlForm Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlGeneric Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlImage Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlInputButton Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlInputCheckBox Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlInputFile Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlInputHidden Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlInputImage Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlInputRadioButton Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlInputText Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlSelect Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •HtmlTable Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlTableCell Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlTableRow Control

- •Properties

- •HtmlTextArea Control

- •Properties

- •Events

- •Index

Chapter 5: Building Web Applications

authentication

outlines configuration settings for user authentication, and is covered in detail in Chapter 14

authorization

specifies users and roles, and controls their access to particular files within an application; discussed more in Chapter 14.

compilation

contains settings that are related to page compilation, and lets you specify the default language that’s used to compile pages

customErrors

used to customize the way errors display

globalization

used to customize character encoding for requests and responses

pages

handles the configuration options for specific ASP.NET pages; allows you to disable session state, buffering, and view state, for example

sessionState

contains configuration information for modifying session state (i.e. variables associated with a particular user’s visit to your site)

trace

contains information related to page and application tracing

configuration section handler declarations

ASP.NET’s configuration file system is so flexible that it allows you to define your own configuration sections. For most purposes, the built-in configuration sections will do nicely, but if we wanted to include some custom configuration sections, we’d need to tell ASP.NET how to handle them. To do so, we’d declare a configuration section handler for each custom configuration section we wanted to create. This is pretty advanced stuff, so we won’t worry about it in this book.

Global.asax

Global.asax is another special file that can be added to the root of an application. It defines subroutines that are executed in response to application-wide events.

170

Global.asax

For instance, Application_Start is executed the first time the application runs (or just after we restart the server). This makes this method the perfect place to execute any initialization code that needs to run when the application loads for the first time. Another useful method is Application_Error, which is called whenever an unhandled error occurs within a page. The following is a list of the handlers that you’ll use most often within the Global.asax file:

Application_Start

called immediately after the application is created; this event occurs once only

Application_End

called immediately before the end of all application instances

Application_Error

called by an unhandled error in the application

Application_BeginRequest

called by every request to the server

Application_EndRequest

called at the end of every request to the server

Application_PreSendRequestHeaders

called before headers are sent to the browser

Application_PreSendRequestContent

called before content is sent to the browser

Application_AuthenticateRequest

called before authenticating a user

Application_AuthorizeRequest

called before authorizing a user

171

Chapter 5: Building Web Applications

Figure 5.26. Creating Global.asax

The Global.asax file is created in the same way as the Web.config file—just select File > New File…, then choose the Global Application Class template, as depicted in Figure 5.26.

Clicking Add will create in the root of your project a new file named Global.asax, which contains empty stubs for a number of event handlers, and comments that explain their roles. A typical event handler in a Global.asax file looks something like this:

Visual Basic

Sub Application_EventName(ByVal sender As Object, _ ByVal e As EventArgs)

…

End Sub

C#

void Application_EventName(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

…

}

172

Using Application State

Be Careful when Changing Global.asax

Be cautious when you add and modify code within the Global.asax file. Any additions or modifications you make within this file will cause the application to restart, so you’ll lose any data stored in application state.

Using Application State

You can store the variables and objects you want to use throughout an entire application in a special object called Application. The data stored in this object is called application state. The Application object also provides you with methods that allow you to share application state data between all the pages in a given ASP.NET application very easily.

Application state is closely related to another concept: session state. The key difference between the two is that session state stores variables and objects for one particular user for the duration of that user’s current visit, whereas application state stores objects and variables that are shared between all users of an application at the same time. Thus, application state is ideal for storing data that’s used by all users of the same application.

In ASP.NET, session and application state are both implemented as collections, or sets of name-value pairs. You can set the value of an application variable named SiteName like this:

Visual Basic

Application("SiteName") = "Dorknozzle Intranet Application"

C#

Application["SiteName"] = "Dorknozzle Intranet Application";

With SiteName set, any pages in the application can read this string:

Visual Basic

Dim appName As String = Application("SiteName")

C#

String appName = Application["SiteName"];

We can remove an object from application state using the Remove method, like so:

Visual Basic

Application.Remove("SiteName")

173

Chapter 5: Building Web Applications

C#

Application.Remove("SiteName");

If you find you have multiple objects and application variables lingering in application state, you can remove them all at once using the RemoveAll method:

Visual Basic

Application.RemoveAll()

C#

Application.RemoveAll();

It’s important to be cautious when using application variables. Objects remain in application state until you remove them using the Remove or RemoveAll methods, or shut down the application in IIS. If you continue to save objects into the application state without removing them, you can place a heavy demand on server resources and dramatically decrease the performance of your applications.

Let’s take a look at application state in action. Application state is very commonly used to maintain hit counters, so our first task in this example will be to build one! Let’s modify the Default.aspx page that Visual Web Developer created for us. Double-click Default.aspx in Solution Explorer, and add a Label control inside the form element. You could drag the control from the Toolbox (in either Design View or Source View) and modify the generated code, or you could simply enter the new code by hand. We’ll also add a bit of text to the page, and change the Label’s ID to myLabel, as shown below:

File: Default.aspx (excerpt)

<form id="form1" runat="server"> <div>

The page has been requested

<asp:Label ID="myLabel" runat="server" /> times!

</div>

</form>

In Design View, you should see your label appear inside the text, as shown in Figure 5.27.

Now, let’s modify the code-behind file to use an application variable that will keep track of the number of hits our page receives. Double-click in any empty space on your form; Visual Web Developer will create a Page_Load subroutine automatically, and display it in the code editor.

174

Using Application State

Figure 5.27. The new label appearing in Design View

Visual Basic |

File: Default.aspx.vb (excerpt) |

Partial Class _Default

Inherits System.Web.UI.Page

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, _

ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles Me.Load

End Sub

End Class

C# |

File: Default.aspx.cs (excerpt) |

public partial class _Default : System.Web.UI.Page

{

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

}

}

Now, let’s modify the automatically generated method by adding the code that we want to run every time the page is loaded. Modify Page_Load as shown below:

Visual Basic File: Default.aspx.vb (excerpt)

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, _ ByVal e As System.EventArgs) Handles Me.Load

' Reset counter when it reaches 10

If Application("PageCounter") >= 10 Then Application.Remove("PageCounter")

End If

' Initialize or increment page counter each time the page loads If Application("PageCounter") Is Nothing Then

Application("PageCounter") = 1 Else

Application("PageCounter") += 1

175

Chapter 5: Building Web Applications

End If |

|

|

' |

Display page |

counter |

myLabel.Text = |

Application("PageCounter") |

|

End |

Sub |

|

|

|

|

C# |

|

File: Default.aspx.cs (excerpt) |

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// Reset counter when it reaches 10

if (Application["PageCounter"] != null && (int)Application["PageCounter"] >= 10)

{

Application.Remove("PageCounter");

}

//Initialize or increment page counter each time the page loads if (Application["PageCounter"] == null)

{

Application["PageCounter"] = 1;

}

else

{

Application["PageCounter"] = (int)Application["PageCounter"] + 1;

}

//Display page counter

myLabel.Text = Convert.ToString(Application["PageCounter"]);

}

Before analyzing the code, press F5 to run the site and ensure that everything works properly. Every time you refresh the page, the hit counter should increase by one until it reaches ten, when it starts over. Now, shut down your browser altogether, and open the page in another browser. We’ve stored the value within application state, so when you restart the application, the page hit counter will remember the value it reached in the original browser, as Figure 5.28 shows.

If you play with the page, reloading it over and over again, you’ll see that the code increments PageCounter every time the page is loaded. First, though, the code verifies that the counter hasn’t reached or exceeded ten requests. If it has, the counter variable is removed from the application state:

Visual Basic |

File: Default.aspx.vb (excerpt) |

|

|

' Reset counter when it reaches 10 |

|

If Application("PageCounter") >= 10 Then |

|

Application.Remove("PageCounter") |

|

End If |

|

|

|

176

Using Application State

Figure 5.28. Using the Application object

C# |

File: Default.aspx.cs (excerpt) |

// Reset counter when it reaches 10 |

|

if (Application["PageCounter"] != null && |

|

(int)Application["PageCounter"] >= 10) |

|

{ |

|

Application.Remove("PageCounter"); |

|

} |

|

Notice that the C# code has to do a little more work than the VB code. You may remember from Chapter 3 that C# is more strict than VB when it comes to variable types. As everything in application state is stored as an Object, C# requires that we cast the value to an integer before we make use of it. This conversion won’t work if PageCounter hasn’t been added to application state, so we also need to check that it’s not equal to null.

Next, we try to increase the hit counter. First of all, we need verify that the counter variable exists in the application state. If it doesn’t, we set it to 1, reflecting that the page is being loaded. To verify that an element exists in VB, we use

Is Nothing:

Visual Basic |

File: Default.aspx.vb (excerpt) |

' Initialize or increment page counter each time the page loads If Application("PageCounter") Is Nothing Then

Application("PageCounter") = 1 Else

Application("PageCounter") += 1 End If

As we’ve already seen, we compare the value to null in C#:

177

Chapter 5: Building Web Applications

C# |

File: Default.aspx.cs (excerpt) |

// Initialize or increment page counter each time the page loads if (Application["PageCounter"] == null)

{

Application["PageCounter"] = 1;

}

else

{

Application["PageCounter"] = (int)Application["PageCounter"] + 1;

}

The last piece of code simply displays the hit counter value in the label.

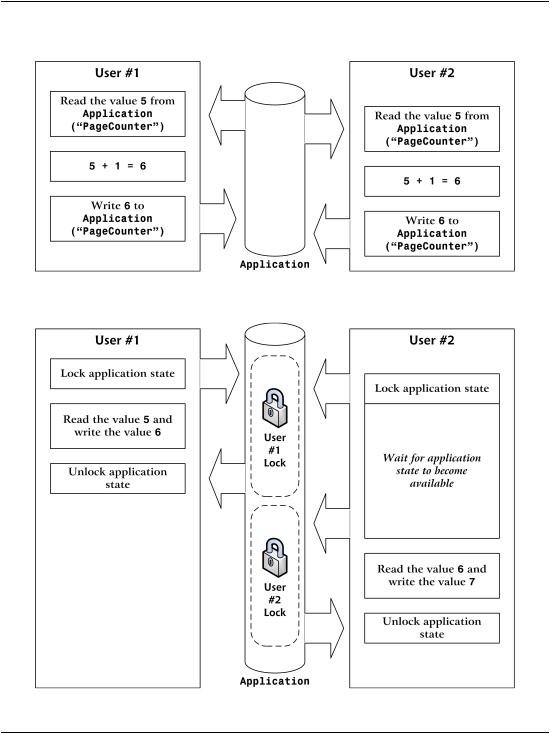

There’s one small problem with our code: if two people were to open the page simultaneously, the value could increment only by one, rather than two. The reason for this has to do with the code that increments the counter:

C# |

File: Default.aspx.cs (excerpt) |

Application["PageCounter"] =

(int)Application["PageCounter"] + 1;

The expression to the right of the = operator is evaluated first; to do this, the server must read the value of the PageCounter value stored in the application. It adds one to this value, then stores the updated value in application state.

Now, let’s imagine that two users visit this page at the same time, and that the web server processes the first user’s request a fraction of a second before the other request. The web form that’s loaded for the first user might read PageCounter from application state and obtain a value of 5, to which it would add 1 to obtain 6. However, before the web form had a chance to store this new value into application state, another copy of the web form, running for the second user, might read PageCounter and also obtain the value 6. Both copies of the page will have read the same value, and both will store an updated value of 6! This tricky situation is illustrated in Figure 5.29.

To avoid this kind of confusion, we should develop the application so that each user locks application state, updates the value, and then unlocks application state so that other users can do the same thing. This process is depicted in Figure 5.30.

178

Using Application State

Figure 5.29. Two users updating application state simultaneously

Figure 5.30. Two users updating application state with locks

179