- •Table of Contents

- •Introduction

- •About This Here Dummies Approach

- •How to Work the Examples in This Book

- •Foolish Assumptions

- •Icons Used in This Book

- •Final Thots

- •The C Development Cycle

- •From Text File to Program

- •The source code (text file)

- •The compiler and the linker

- •Running the final result

- •Save It! Compile and Link It! Run It!

- •Reediting your source code file

- •Dealing with the Heartbreak of Errors

- •The autopsy

- •Repairing the malodorous program

- •Now try this error!

- •The Big Picture

- •Other C Language Components

- •Pop Quiz!

- •The Helpful RULES Program

- •The importance of being \n

- •Breaking up lines\ is easy to do

- •The reward

- •More on printf()

- •Printing funky text

- •Escape from printf()!

- •A bit of justification

- •Putting scanf together

- •The miracle of scanf()

- •Experimentation time!

- •Adding Comments

- •A big, hairy program with comments

- •Why are comments necessary?

- •Bizarr-o comments

- •C++ comments

- •Using Comments to Disable

- •The More I Want, the More I gets()

- •Another completely rude program example

- •And now, the bad news about gets()

- •The Virtues of puts()

- •Another silly command-prompt program

- •puts() and gets() in action

- •More insults

- •puts() can print variables

- •The Ever-Changing Variable

- •Strings change

- •Running the KITTY

- •Hello, integer

- •Using an integer variable in the Methuselah program

- •Assigning values to numeric variables

- •Entering numeric values from the keyboard

- •The atoi() function

- •So how old is this Methuselah guy, anyway?

- •Basic mathematical symbols

- •How much longer do you have to live to break the Methuselah record?

- •The direct result

- •Variable names verboten and not

- •Presetting variable values

- •The old random-sampler variable program

- •Maybe you want to chance two pints?

- •Multiple declarations

- •Constants and Variables

- •Dreaming up and defining constants

- •The handy shortcut

- •The #define directive

- •Real, live constant variables

- •Numbers in C

- •Why use integers? Why not just make every number floating-point?

- •Integer types (short, long, wide, fat, and so on)

- •How to Make a Number Float

- •The E notation stuff

- •Single-character variables

- •Char in action

- •Stuffing characters into character variables

- •Reading and Writing Single Characters

- •The getchar() function

- •The putchar() function

- •Character Variables As Values

- •Unhappily incrementing your weight

- •Bonus program! (One that may even have a purpose in life)

- •The Sacred Order of Precedence

- •A problem from the pages of the dentistry final exam

- •The confounding magic-pellets problem

- •Using parentheses to mess up the order of precedence

- •The computer-genie program example

- •The if keyword, up close and impersonal

- •A question of formatting the if statement

- •The final solution to the income-tax problem

- •Covering all the possibilities with else

- •The if format with else

- •The strange case of else-if and even more decisions

- •Bonus program! The really, really smart genie

- •The World of if without Values

- •The problem with getchar()

- •Meanwhile, back to the GREATER problem

- •Another, bolder example

- •Exposing Flaws in logic

- •A solution (but not the best one)

- •A better solution, using logic

- •A logical AND program for you

- •For Going Loopy

- •For doing things over and over, use the for keyword

- •Having fun whilst counting to 100

- •Beware of infinite loops!

- •Breaking out of a loop

- •The break keyword

- •The Art of Incrementation

- •O, to count backward

- •How counting backward fits into the for loop

- •More Incrementation Madness

- •Leaping loops!

- •Counting to 1,000 by fives

- •Cryptic C operator symbols, Volume III: The madness continues

- •The answers

- •The Lowdown on while Loops

- •Whiling away the hours

- •Deciding between a while loop and a for loop

- •Replacing those unsightly for(;;) loops with elegant while loops

- •C from the inside out

- •The Down-Low on Upside-Down do-while Loops

- •The devil made me do-while it!

- •do-while details

- •The always kosher number-checking do-while loop

- •Break the Brave and Continue the Fool

- •The continue keyword

- •The Sneaky switch-case Loops

- •The switch-case Solution to the LOBBY Program

- •The Old switch-case Trick

- •The Special Relationship between while and switch-case

- •A potentially redundant program in need of a function

- •The noble jerk() function

- •Prototyping Your Functions

- •Prototypical prototyping problems

- •A sneaky way to avoid prototyping problems

- •The Tao of Functions

- •The function format

- •How to name your functions

- •Adding some important tension

- •Making a global variable

- •An example of a global variable in a real, live program

- •Marching a Value Off to a Function

- •How to send a value to a function

- •Avoiding variable confusion (must reading)

- •Functions That Return Stuff

- •Something for your troubles

- •Finally, the computer tells you how smart it thinks you are

- •Return to sender with the return keyword

- •Now you can understand the main() function

- •Give that human a bonus!

- •Writing your own dot-H file

- •A final warning about header files

- •What the #defines Are Up To

- •Avoiding the Topic of Macros

- •A Quick Review of printf()

- •The printf() Escape Sequences

- •The printf() escape-sequence testing program deluxe

- •Putting PRINTFUN to the test

- •The Complex printf() Format

- •The printf() Conversion Characters

- •More on Math

- •Taking your math problems to a higher power

- •Putting pow() into use

- •Rooting out the root

- •Strange Math? You Got It!

- •Something Really Odd to End Your Day

- •The perils of using a++

- •Oh, and the same thing applies to a --

- •Reflections on the strange ++a phenomenon

- •On Being Random

- •Using the rand() function

- •Planting a random-number seed

- •Randoming up the RANDOM program

- •Streamlining the randomizer

- •Arrays

- •Strings

- •Structures

- •Pointers

- •Linked Lists

- •Binary Operators

- •Interacting with the Command Line

- •Disk Access

- •Interacting with the Operating System

- •Building Big Programs

- •Use the Command-Line History

- •Use a Context-Colored Text Editor

- •Carefully Name Your Variables

- •Breaking Out of a Loop

- •Work on One Thing at a Time

- •Break Up Your Code

- •Simplify

- •Talk through the Program

- •Set Breakpoints

- •Monitor Your Variables

- •Document Your Work

- •Use Debugging Tools

- •Use a C Optimizer

- •Read More Books!

- •Setting Things Up

- •The C language compiler

- •The place to put your stuff

- •Making Programs

- •Finding your learn directory or folder

- •Running an editor

- •Compiling and linking

- •Index

Chapter 15

C You Again

In This Chapter

Understanding the loop

Repeating chunks of code with for

Using a loop to count

Displaying an ASCII table by using a loop

Avoiding the endless loop

Breaking a loop with break

One thing computers enjoy doing more than anything else is repeating themselves. Humans? We think that it’s punishment to tell a kid to write

“National Geographic films are not to be giggled at” 100 times on a chalkboard. Computers? They don’t mind a bit. They enjoy it, in fact.

Next to making decisions with if, the power in your programs derives from their ability to repeat things. The only problem with that is getting them to stop, which is why you need to know how if works before you progress into the looping statements. This chapter begins your looping journey by intro ducing you to the most ancient of the loopy commands, for.

To find out about the if statement, refer to Chapters 12 though 14.

It may behoove you to look at Table 12-1, in Chapter 12, which contains comparison functions used by both the if and for commands.

For Going Loopy

Doing things over and over is referred to as looping. When a computer program mer writes a program that counts to one zillion, he writes a loop. The loop is called such because it’s a chunk of programming instructions — code — that is executed a given number of times. Over and over.

186 Part III: Giving Your Programs the Ability to Run Amok

As an example of a loop, consider the common Baby-Mother interaction program:

Baby picks up spoon.

Baby throws spoon on floor; Baby laughs.

Mommy picks up spoon from floor.

Mommy places spoon before Baby.

Repeat.

This primitive program contains a loop. The loop is based on “Repeat,” which tells you that the entire sequence of steps repeats itself.

Unfortunately, the steps in the preceding primitive program don’t contain any stopping condition. Therefore, it’s what is known as an endless loop. Most loop ing statements in computer programming languages have some sort of condi tion — like an if statement — that tells the program when to stop repeating (or that, at least, such a thing is desired.)

A simple modification to the program can fix the endless loop situation:

Repeat until Mommy learns not to put spoon before Baby.

Now, the program has a stopping condition for the loop.

In conclusion, loops have three parts:

A start

The middle part (the part that is repeated)

An end

These three parts are what make up a loop. The start is where the loop is set up, usually some programming-language instruction that says “I’m going to do a loop here — stand by to repeat something.” The middle part consists of the instructions that are repeated over and over. Finally, the end marks the end of the repeating part or a condition on which the loop ends (“until Mommy learns,” in the preceding example).

The C language has several different types of loops. It has for loops, which you read about in this chapter; while loops and do-while loops; and the ugly goto keyword, covered elsewhere in this book and in more detail in its companion book, C All-in-One Desk Reference For Dummies

(Wiley).

The instructions held within a loop are executed a specific number of times, or they can be executed until a certain condition is met. For example, you can tell the computer, “Do this a gazillion times” or “Do this until your thumb gets tired.” Either way, several instructions are executed over and over.

Chapter 15: C You Again 187

After the loop has finished going through its rounds, the program contin ues. But while the loop is, well, “looping,” the same part of the program is run over and over.

Repetitive redundancy, I don’t mind

The following source code is for OUCH.C, a program which proves that com puters don’t mind doing things over and over again. No, not at their expense. Not while you sit back, watch them sweat, and laugh while you snarf popcorn and feast on carbonated beverages.

What this program does is to use the for keyword, one of the most basic loop ing commands in the C language. The for keyword creates a small loop that repeats a single printf() command five times:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int i;

for(i=0 ; i<5 ; i=i+1)

{

printf(“Ouch! Please, stop!\n”);

}

return(0);

}

Enter this source code into your editor.

The new deal here is the for keyword, at Line 7. Type what happens in there carefully. Notice that the line which begins with for doesn’t end with a semi colon. Instead, it’s followed by a set of curly braces — just like the if state ment. (It’s exactly like the if statement, in fact.)

Save the file as OUCH.C.

Compile OUCH.C by using your compiler. Be on the lookout for errors. A semicolon may be missing in for’s parentheses.

Run the final program. You see the following displayed:

Ouch! Please, stop!

Ouch! Please, stop!

Ouch! Please, stop!

Ouch! Please, stop!

Ouch! Please, stop!

188 Part III: Giving Your Programs the Ability to Run Amok

See? Repetition doesn’t hurt the PC. Not one bit.

The for loop has a start, a middle, and an end. The middle part is the printf() statement — the part that gets repeated. The rest of the loop, the start and end, are nestled within the for keyword’s parentheses. (The next section deciphers how this stuff works.)

Just as with the if structure, when only one statement belongs to the for command, you could write it like this:

for(i=0 ; i<5 ; i=i+1)

printf(“Ouch! Please, stop!\n”);

The curly braces aren’t required when you have only one statement that’s repeated. But, if you have more than one, they’re a must.

The for loop repeats the printf() statement five times.

Buried in the for loop is the following statement:

i=i+1

This is how you add 1 to a variable in the C language. It’s called incre mentation, and you should read Chapter 11 if you don’t know what it is.

Don’t worry if you can’t understand the for keyword just yet. Read through this whole chapter, constantly muttering “I will understand this stuff” over and over. Then go back and reread it if you need to. But read it all straight through first.

For doing things over and over, use the for keyword

The word for is one of those words that gets weirder and weirder the more you say it: for, for, fore, four, foyer. . . . For he’s a jolly good fellow. These are for your brother. For why did you bring me here? An eye for an eye. For the better to eat you with, my dear. Three for a dollar. And on and on. For it can be maddening.

In the C programming language, the for keyword sets up a loop, logically called a for loop. The for keyword defines a starting condition, an ending condition, and the stuff that goes on while the loop is being executed over and over. The format can get a little deep, so take this one step at a time:

for(starting; while_true; do_this)

statement;

Chapter 15: C You Again 189

After the keyword for comes a set of parentheses. Inside the parentheses are three items, separated by two semicolons. A semicolon doesn’t end this line.

The first item is starting, which sets up the starting condition for the loop. It’s usually some variable that is initialized to a value. In OUCH.C, it’s i=0.

The second item is while_true. It tells for to keep looping; as long as the condition specified by while_true is true, the loop is repeated. Typically, while_true is a comparison, similar to one found in an if command. In OUCH.C, it’s i<5.

The final item, do_this, tells the for keyword what to do each time the loop is executed once. In OUCH.C, the job that is done here is to increment variable i one notch: i=i+1.

The statement item is a statement that follows and belongs to the for key word. statement is repeated a given number of times as the for keyword works through its loops. This statement must end with a semicolon.

If more than one statement belongs to the for structure, you must use curly braces to corral them:

for(starting; while_true; do_this)

{

statement;

statement; /* etc. */

}

Note that the statements are optional. You can have a for loop that looks like this:

for(starting; while_true; do_this)

;

In this case, the single semicolon is the “statement” that for repeats.

One of the most confusing aspects of the for keyword is what happens to the three items inside its parentheses. Take heart: It confuses both begin ners and the C lords alike (though they don’t admit to it).

The biggest mistake with the for loop? Using commas rather than semi colons. Those are semicolons inside them thar parentheses!

Some C programmers leave out the starting and do_this parts of the for command. Although that’s okay for them, I don’t recommend it for beginners. Just don’t let it shock you if you ever see it. Remember that both semicolons are always required inside for’s parentheses.

190 Part III: Giving Your Programs the Ability to Run Amok

Tearing through OUCH.C a step at a time

I admit that the for loop isn’t the easiest of C’s looping instructions to under stand. The problem is all the pieces. It would be easier to say, for example:

for(6)

{

/* statements */

}

and then repeat the stuff between the curly braces six times. But what that does is limit the power of the for command’s configuration.

To help you better understand how for’s three parentheses’ pieces’ parts make sense, I use the following for statement from OUCH.C as an example:

for(i=0 ; i<5 ; i=i+1)

The for loop uses the variable i to count the number of times it repeats its statements.

The first item tells the for loop where to begin. In this line, that’s done by setting the integer variable i equal to 0. This plain old C language statement stuffs a variable with a value:

i=0

The value 0 slides through the parentheses into the integer variable i. No big deal.

The second item is a condition — like you would find in an if statement — that tells the for loop how long to keep going; to keep repeating itself over and over as long as the condition that’s specified is true. In the preceding code, as long as the statement i<5 (the value of the variable i is less than 5) is true, the loop continues repeating. It’s the same as the following if statement:

if (i<5)

If the value of variable i is less than 5, keep going.

The final item tells the for loop what to do each time it repeats. Without this item, the loop would repeat forever: i is equal to 0, and the loop is repeated as long as i<5 (the value of i is less than 5). That condition is true, so for would go on endlessly, like a federal farm subsidy. However, the last item tells for to increment the value of the i variable each time it loops:

i=i+1

Chapter 15: C You Again 191

The compiler takes the value of the variable i and adds 1 to it each time the for loop is run through once. (Refer to Chapter 11 for more info on the art of incrementation.)

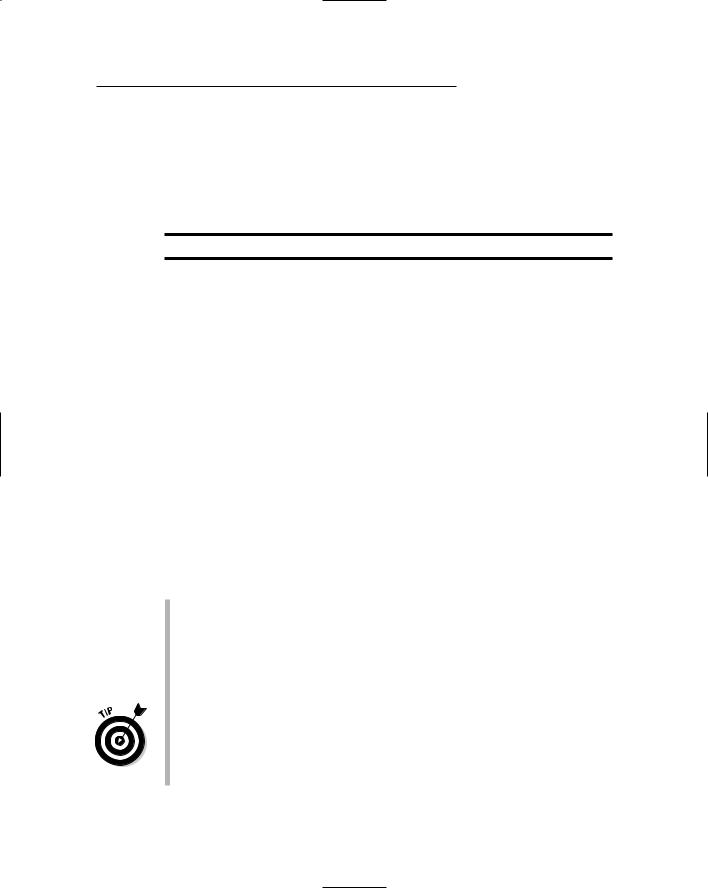

Altogether, the for loop works out to repeat itself — and any statements that belong to it — a total of five times. Table 15-1 shows how it works.

Table 15-1 How the Variable i Works Its Way through the for Loop

Value of i |

Is i<5 true? |

Statement |

Do This |

i=0 |

Yes, keep looping← |

printf() . . . (1) |

i=0+1 |

|

|

|

|

i=1 |

Yes, keep looping← |

printf() . . . (2) |

i=1+1 |

|

|

|

|

i=2 |

Yes, keep looping← |

printf() . . . (3) |

i=2+1 |

|

|

|

|

i=3 |

Yes, keep looping← |

printf() . . . (4) |

i=3+1 |

|

|

|

|

i=4 |

Yes, keep looping← |

printf() . . . (5) |

i=4+1 |

|

|

|

|

i=5 |

No — stop now! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Table 15-1, the value of the variable i starts out equal to 0, as set up in the for statement. Then, the second item — the comparison — is tested. Is i<5 true? If so, the loop marches on.

As the loop works, the third part of the for statement is calculated and the value of i is incremented. Along with that, any statements belonging to the for command are executed. When those statements are done, the comparison i<5 is made again and the loop either repeats or stops based on the results of that comparison.

The for loop can be cumbersome to understand because it has so many parts. However, it’s the best way in your C programs to repeat a group of statements a given number of times.

The third item in the for statement’s parentheses — do_this — is exe cuted only once for each loop. It’s true whether for has zero, one, or several statements belonging to it.

Where most people screw up with the for loop is the second item. They remember that the first item means “start here,” but they think that the second item is “end here.” It’s not! The second item means “keep looping while this condition is true.” It works like an if comparison. The compiler doesn’t pick up and flag it as a boo-boo, but your program doesn’t run properly when you make this mistake.