- •Preface

- •Contents

- •Chapter 1

- •1.1 International Financial Markets

- •Foreign Exchange

- •Covered Interest Parity

- •Uncovered Interest Parity

- •Futures Contracts

- •1.2 National Accounting Relations

- •National Income Accounting

- •The Balance of Payments

- •1.3 The Central Bank’s Balance Sheet

- •Chapter 2

- •2.1 Unrestricted Vector Autoregressions

- •Lag-Length Determination

- •Granger Causality, Econometric Exogeniety and Causal

- •Priority

- •The Vector Moving-Average Representation

- •Impulse Response Analysis

- •Forecast-Error Variance Decomposition

- •Potential Pitfalls of Unrestricted VARs

- •2.2 Generalized Method of Moments

- •2.3 Simulated Method of Moments

- •2.4 Unit Roots

- •The Levin—Lin Test

- •The Im, Pesaran and Shin Test

- •The Maddala and Wu Test

- •Potential Pitfalls of Panel Unit-Root Tests

- •2.6 Cointegration

- •The Vector Error-Correction Representation

- •2.7 Filtering

- •The Spectral Representation of a Time Series

- •Linear Filters

- •The Hodrick—Prescott Filter

- •Chapter 3

- •The Monetary Model

- •Cassel’s Approach

- •The Commodity-Arbitrage Approach

- •3.5 Testing Monetary Model Predictions

- •MacDonald and Taylor’s Test

- •Problems

- •Chapter 4

- •The Lucas Model

- •4.1 The Barter Economy

- •4.2 The One-Money Monetary Economy

- •4.4 Introduction to the Calibration Method

- •4.5 Calibrating the Lucas Model

- •Appendix—Markov Chains

- •Problems

- •Chapter 5

- •Measurement

- •5.2 Calibrating a Two-Country Model

- •Measurement

- •The Two-Country Model

- •Simulating the Two-Country Model

- •Chapter 6

- •6.1 Deviations From UIP

- •Hansen and Hodrick’s Tests of UIP

- •Fama Decomposition Regressions

- •Estimating pt

- •6.2 Rational Risk Premia

- •6.3 Testing Euler Equations

- •Volatility Bounds

- •6.4 Apparent Violations of Rationality

- •6.5 The ‘Peso Problem’

- •Lewis’s ‘Peso-Problem’ with Bayesian Learning

- •6.6 Noise-Traders

- •Problems

- •Chapter 7

- •The Real Exchange Rate

- •7.1 Some Preliminary Issues

- •7.2 Deviations from the Law-Of-One Price

- •The Balassa—Samuelson Model

- •Size Distortion in Unit-Root Tests

- •Problems

- •Chapter 8

- •The Mundell-Fleming Model

- •Steady-State Equilibrium

- •Exchange rate dynamics

- •8.3 A Stochastic Mundell—Fleming Model

- •8.4 VAR analysis of Mundell—Fleming

- •The Eichenbaum and Evans VAR

- •Clarida-Gali Structural VAR

- •Appendix: Solving the Dornbusch Model

- •Problems

- •Chapter 9

- •9.1 The Redux Model

- •9.2 Pricing to Market

- •Full Pricing-To-Market

- •Problems

- •Chapter 10

- •Target-Zone Models

- •10.1 Fundamentals of Stochastic Calculus

- •Ito’s Lemma

- •10.3 InÞnitesimal Marginal Intervention

- •Estimating and Testing the Krugman Model

- •10.4 Discrete Intervention

- •10.5 Eventual Collapse

- •Chapter 11

- •Balance of Payments Crises

- •Flood—Garber Deterministic Crises

- •11.2 A Second Generation Model

- •Obstfeld’s Multiple Devaluation Threshold Model

- •Bibliography

- •Author Index

- •Subject Index

Chapter 8

The Mundell-Fleming Model

Mundell [108]—Fleming [54] is the IS-LM model adapted to the open economy. Although the framework is rather old and ad hoc the basic framework continues to be used in policy related research (Williamson [132], Hinkle and Montiel [107], MacDonald and Stein [98]). The hallmark

of the Mundell-Fleming framework is that goods prices exhibit stickiness whereas asset markets–including the foreign exchange market– are continuously in equilibrium. The actions of policy makers play a major role in these models because the presence of nominal rigidities opens the way for nominal shocks to have real e ects. We begin with a simple static version of the model. Next, we present the dynamic but deterministic Mundell-Fleming model due to Dornbusch [39]. Third, we present a stochastic Mundell-Fleming model based on Obstfeld [111].

8.1A Static Mundell-Fleming Model

This is a Keynesian model where goods prices are Þxed for the duration of the analysis. The home country is small in sense that it takes foreign variables as Þxed. All variables except the interest rate are in logarithms.

Equilibrium in the goods market is given by an open economy version of the IS curve. There are three determinants of the demand for domestic goods. First, expenditures depend positively on own income y through the absorption channel. An increase in income leads to higher

229

230 |

CHAPTER 8. THE MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

consumption, most of which is spent on domestically produced goods. Second, domestic goods demand depends negatively on the interest rate i through the investment—saving channel. Since goods prices are Þxed, the nominal interest rate is identical to the real interest rate. Higher interest rates reduce investment spending and may encourage a reduction of consumption and an increase in saving. Third, demand for home goods depends positively on the real exchange rate s+p −p. An increase in the real exchange rate lowers the price of domestic goods relative to foreign goods leading expenditures by residents of the home country as well as residents of the rest of the world to switch toward domestically produced goods. We call this the expenditure switching e ect of exchange rate ßuctuations. In equilibrium, output equals expenditures which is given by the IS curve

y = δ(s + p − p) + γy − σi + g, |

(8.1) |

where g is an exogenous shifter which we interpret as changes in Þscal policy. The parameters δ, γ, and σ are deÞned to be positive with 0 < γ < 1.

As in the monetary model, log real money demand md −p depends positively on log income y and negatively on the nominal interest rate i which measures the opportunity cost of holding money. Since the price level is Þxed, the nominal interest rate is also the real interest rate, r. In logarithms, equilibrium in the money market is represented by the LM curve

m − p = φy − λi. |

(8.2) |

The country is small and takes the world price level and world interest rate as given. For simplicity, we Þx p = 0. The domestic price level is also Þxed so we might as well set p = 0.

Capital is perfectly mobile across countries.1 International capital market equilibrium is given by uncovered interest parity with static

1Given the rapid pace at which international Þnancial markets are becoming integrated, analyses under conditions of imperfect capital mobility is becoming less relevant. However, one can easily allow for imperfect capital mobility by modeling both the current account and the capital account and setting the balance of payments to zero (the external balance constraint) as an equilibrium condition. See the end-of-chapter problems.

8.1. A STATIC MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

231 |

expectations2 |

|

i = i . |

(8.3) |

Substitute (8.3) into (8.1) and (8.2). Totally di erentiate the result and rearrange to obtain the two-equation system

|

|

φδ |

|

" |

|

φσ |

|

# |

|

φ |

|

|

||

dm |

= |

1 − γ |

ds − |

|

λ + |

1 − γ |

|

di + |

1 − γ |

dg, |

(8.4) |

|||

|

|

δ |

|

σ |

|

di + |

|

dg |

|

|

|

|||

dy |

= |

|

ds − |

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

(8.5) |

|||

1 − γ |

1 − γ |

1 − γ |

|

|

||||||||||

All of our comparative statics results come from these two equations.

Adjustment under Fixed Exchange Rates

Domestic credit expansion. Assume that the monetary authorities are credibly committed to Þxing the exchange rate. In this environment, the exchange rate is a policy variable. As long as the Þx is in e ect, we set ds = 0. Income y and the money supply m are endogenous variables.

Suppose the authorities expand the domestic credit component of the money supply. Recall from (1.22) that the monetary base is made up of the sum of domestic credit and international reserves. In the absence of any other shocks (di = 0, dg = 0), we see from (8.4) that there is no long-run change in the money supply dm = 0 and from (8.5), there is no long-run change in output. The initial attempt to expand the money supply by increasing domestic credit results in an o setting loss of international reserves. Upon the initial expansion of domestic credit, the money supply does increase. The interest rate must remain Þxed at the world rate, however, and domestic residents are unwilling to hold additional money at i . They eliminate the excess money by accumulating foreign interest bearing assets and run a temporary balance of payments deÞcit. The domestic monetary authorities evidently have no control over the money supply in the long run and monetary policy is said to be ine ective as a stabilization tool under a Þxed exchange rate regime with perfect capital mobility.

2Agents expect no change in the exchange rate.

232 |

CHAPTER 8. THE MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

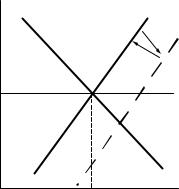

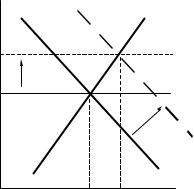

The situation is depicted graphically in Figure 8.1. First, the expansion of domestic credit shifts the LM curve out. To maintain interest parity there is an incipient capital outßow. The central bank defends the exchange rate by selling reserves. This loss of reserves causes the LM curve to shift back to its original position.

r |

|

|

LM |

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

a |

r* |

FF |

|

b |

|

IS |

|

y |

|

y0 |

Figure 8.1: Domestic credit expansion shifts the LM curve out. The central bank loses reserves to accommodate the resulting capital outßow which shifts the LM curve back in.

(136) |

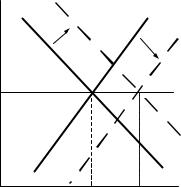

Domestic currency devaluation. |

From (8.4)-(8.5), you have |

dy = [δ/(1−γ)]ds > 0 and dm = [φδ/(1 −γ)]ds > 0. The expansionary |

||

|

e ects of a devaluation are shown in Figure 8.2. The devaluation makes |

|

|

domestic goods more competitive and expenditures switch towards do- |

|

mestic goods. This has a direct e ect on aggregate expenditures. In a closed economy, the expansion would lead to an increase in the interest rate but in the open economy under perfect capital mobility, the expansion generates a capital inßow. To maintain the new exchange rate, the central bank accommodates the capital ßows by accumulating foreign exchange reserves with the result that the LM curve shifts out.

One feature that the model misses is that in real world economies, the country’s foreign debt is typically denominated in the foreign currency so the devaluation increases the country’s real foreign debt burden.

8.1. A STATIC MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

233 |

r |

|

|

|

|

|

LM |

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b |

|

r* |

a |

c |

FF |

|

|

||

|

|

IS |

y |

|

y0 |

|

|

|

y1 |

|

Figure 8.2: Devaluation shifts the IS curve out. The central bank accumulates reserves to accommodate the resulting capital inßow which shifts the LM curve out.

Fiscal policy shocks. The results of an increase in government spending

are dy = [1/(1 − γ)]dg and dm = [φ/(1 − γ)]dg which is expansionary. (137) The increase in g shifts the IS curve to the right and has a direct e ect

on expenditures. Fiscal policy works the same way as a devaluation and is said to be an e ective stabilization tool under Þxed exchange rates and perfect capital mobility.

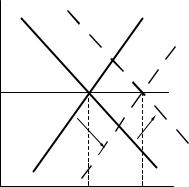

Foreign interest rate shocks. An increase in the foreign interest rate has a contractionary e ect on domestic output and the money supply, dy = −(σ/(1 − γ))di , and dm = −(λ + φσ/(1 − γ))di . The increase i creates an incipient capital outßow. To defend the exchange rate, the monetary authorities sell foreign reserves which causes the money supply to contract. The situation is depicted graphically in Figure 8.3.

Implied International transmissions. Although we are working with the small-country version of the model, we can qualitatively deduce how policy shocks would be transmitted internationally in a two-country model. If the increase in i was the result of monetary tightening in the large foreign country, output also contracts abroad. We say that

234 |

CHAPTER 8. THE MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

r |

|

|

LM |

|

(1) |

r* |

FF |

(2) |

|

|

IS |

|

y |

y1 |

y0 |

Figure 8.3: An increase in i generates a capital outßow, a loss of central bank reserves, and a contraction of the domestic money supply.

monetary shocks are positively transmitted internationally as they lead to positive output comovements at home and abroad. If the increase in i was the result of expansionary foreign government spending, foreign output expands whereas domestic output contracts. Aggregate expenditure shocks are said to be negatively transmitted internationally under a Þxed exchange rate regime.

A currency devaluation has negative transmission e ects. The devaluation of the home currency is equivalent to a revaluation of the foreign currency. Since the domestic currency devaluation has an expansionary e ect on the home country, it must have a contractionary e ect on the foreign country. A devaluation that expands the home country at the expense of the foreign country is referred to as a beggar- thy-neighbor policy.

Flexible Exchange Rates

When the authorities do not intervene in the foreign exchange market, s and y are endogenous in the system (8.4)-(8.5) and the authorities regain control over m, which is treated as exogenous.

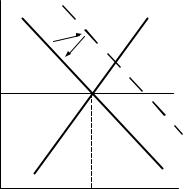

Domestic credit expansion. An expansionary monetary policy generates an incipient capital outßow which leads to a depreciation of the

8.1. A STATIC MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

235 |

r |

|

|

LM |

a |

c |

r* |

FF |

(1) |

(2) |

b |

|

|

IS |

y0 |

y |

y1 |

Figure 8.4: Expansion of domestic credit shifts LM curve out. Incipient capital outßow is o set by depreciation of domestic currency which shifts the IS curve out.

home currency ds = [(1 − γ)/φδ]dm > 0. The expenditure switching e ect of the depreciation increases expenditures on the home good and has an expansionary e ect on output dy = (1/φ)dm > 0.

The situation is represented graphically in Figure 8.4 where the expansion of domestic credit shifts the LM curve to the right. In the closed economy, the home interest rate would fall but in the small open economy with perfect capital mobility, the result is an incipient capital outßow which causes the home currency to depreciate (s increases) and the IS curve to shift to the right. The e ectiveness of monetary policy is restored under ßexible exchange rates.

Fiscal policy. Fiscal policy becomes ine ective as a stabilization tool under ßexible exchange rates and perfect capital mobility. The situation is depicted in Figure 8.5. An expansion of government spending is represented by an initial outward shift in the IS curve which leads to an incipient capital inßow and an appreciation of the home currency ds = −(1/δ)dg < 0. The resulting expenditure switch forces a subsequent inward shift of the IS curve. The contractionary e ects of the induced appreciation o sets the expansionary e ect of the government spending leaving output unchanged dy = 0. The model predicts an international

236 |

CHAPTER 8. THE MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

r |

|

|

LM |

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

r* |

FF |

|

IS |

|

y |

|

y0 |

Figure 8.5: Expansionary Þscal policy shifts IS curve out. Incipient capital inßow generates an appreciation which shifts the IS curve back to its original position.

version of crowding out. Recipients of government spending expand at the expense of the traded goods sector.

Interest rate shocks. An increase in the foreign interest rate leads to an incipient capital outßow and a depreciation given by ds = [(λ(1 − γ) + σφ)/φδ]di > 0. The expenditure-switching e ect of the depreciation causes the IS curve in Figure 8.6 to shift out. The expansionary e ect of the depreciation more than o sets the contractionary e ect of the higher interest rate resulting in an expansion of output dy = (λ/φ)di > 0.

International transmission e ects. If the interest rate shock was caused by a contraction in foreign money, the expansion of domestic output would be associated with a contraction of foreign output and monetary policy shocks are negatively transmitted from one country to another under ßexible exchange rates. Government spending, on the other hand is positively transmitted. If the increase in the foreign interest rate was precipitated by an expansion of foreign government spending, we would observe expansion in output both abroad and at home.

8.2. DORNBUSCH’S DYNAMIC MUNDELL—FLEMING MODEL237

r |

|

|

LM |

(1) |

|

r* |

FF |

|

(2) |

|

IS |

|

y |

y0 |

y1 |

Figure 8.6: An increase in the world interest rate generates an incipient capital outßow, leading to a depreciation and an outward shift in the IS curve.

8.2Dornbusch’s Dynamic Mundell—Fleming Model

As we saw in Chapter 3, the exchange rate in a free ßoat behaves much like stock prices. In particular, it exhibits more volatility than macroeconomic fundamentals such as the money supply and real GDP. Dornbusch [39] presents a dynamic version of the Mundell—Fleming model that explains excess exchange rate volatility in a deterministic perfect foresight setting. The key feature of the model is that the asset market adjusts to shocks instantaneously while goods market adjustment takes time.

The money market is continuously in equilibrium which is represented by the LM curve, restated here as

m − p = φy − λi. |

(8.6) |

To allow for possible disequilibrium in the goods market, let y denote actual output which is assumed to be Þxed, and yd denote the demand for home output. The demand for domestic goods depends on the real

238 |

CHAPTER 8. THE MUNDELL-FLEMING MODEL |

|

exchange rate s + p − p, real income y, and the interest rate i3 |

|

|

|

yd = δ(s − p) + γy − σi + g, |

(8.7) |

where we have set p = 0.

Denote the time derivative of a function x of time with a “dot”

xú (t) = dx(t)/dt. Price level dynamics are governed by the rule |

|

pú = π(yd − y), |

(8.8) |

where the parameter 0 < π < ∞ indexes the speed of goods market adjustment.4 (8.8) says that the rate of inßation is proportional to excess demand for goods. Because excess demand is always Þnite, the rate of change in goods prices is always Þnite so there are no jumps in price level. If the price level cannot jump, then at any point in time it is instantaneously Þxed. The adjustment of the price-level towards its long-run value must occur over time and it is in this sense that goods prices are sticky in the Dornbusch model.

International capital market equilibrium is given by the uncovered interest parity condition

i = i + súe, |

(8.9) |

where súe is the expected instantaneous depreciation rate. Let s¯ be the steady-state nominal exchange rate. The model is completed by specifying the forward—looking expectations

súe = θ(¯s − s). |

(8.10) |

Market participants believe that the instantaneous depreciation is proportional to the gap between the current exchange rate and its long-run value but to be model consistent, agents must have perfect foresight. This means that the factor of proportionality θ must be chosen to be consistent with values of the other parameters of the model. This perfect foresight value of θ can be solved for directly, (as in the chapter

3Making demand depend on the real interest rate results in the same qualitative conclusions, but messier algebra.

4Low values of π indicate slow adjustment. Letting π → ∞ allows goods prices to adjust instantaneously which allows the goods market to be in continuous equilibrium.