- •Contents

- •1 Russian

- •1.1 The Russian language

- •1.1.1 Russian then and now

- •1.1.2 Levels of language

- •1.2 Describing Russian grammar

- •1.2.1 Conventions of notation

- •1.2.2 Abbreviations

- •1.2.3 Dictionaries and grammars

- •1.2.4 Statistics and corpora

- •1.2.5 Strategies of describing Russian grammar

- •1.2.6 Two fundamental concepts of (Russian) grammar

- •1.3 Writing Russian

- •1.3.1 The Russian Cyrillic alphabet

- •1.3.2 A brief history of the Cyrillic alphabet

- •1.3.3 Etymology of letters

- •1.3.4 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (basics)

- •1.3.5 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (refinements)

- •1.3.6 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (lexical idiosyncrasies)

- •1.3.7 Transliteration

- •2 Sounds

- •2.1 Sounds

- •2.2 Vowels

- •2.2.1 Stressed vowels

- •2.2.3 Vowel duration

- •2.2.4 Unstressed vowels

- •2.2.5 Unpaired consonants [ˇs ˇz c] and unstressed vocalism

- •2.2.6 Post-tonic soft vocalism

- •2.2.7 Unstressed vowels in sequence

- •2.2.8 Unstressed vowels in borrowings

- •2.3 Consonants

- •2.3.1 Classification of consonants

- •2.3.2 Palatalization of consonants

- •2.3.3 The distribution of palatalized consonants

- •2.3.4 Palatalization assimilation

- •2.3.5 The glide [j]

- •2.3.6 Affricates

- •2.3.7 Soft palatal fricatives

- •2.3.8 Geminate consonants

- •2.3.9 Voicing of consonants

- •2.4 Phonological variation

- •2.4.1 General

- •2.4.2 Phonological variation: idiomaticity

- •2.4.3 Phonological variation: systemic factors

- •2.4.4 Phonological variation: phonostylistics and Old Muscovite pronunciation

- •2.5 Morpholexical alternations

- •2.5.1 Preliminaries

- •2.5.2 Consonant grades

- •2.5.3 Types of softness

- •2.5.4 Vowel grades

- •2.5.5 Morphophonemic {o}

- •3 Inflectional morphology

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Conjugation of verbs

- •3.2.1 Verbal categories

- •3.2.2 Conjugation classes

- •3.2.3 Stress patterns

- •3.2.4 Conjugation classes: I-Conjugation

- •3.2.5 Conjugation classes: suffixed E-Conjugation

- •3.2.6 Conjugation classes: quasisuffixed E-Conjugation

- •3.2.7 Stress in verbs: retrospective

- •3.2.8 Irregularities in conjugation

- •3.2.9 Secondary imperfectivization

- •3.3 Declension of pronouns

- •3.3.1 Personal pronouns

- •3.3.2 Third-person pronouns

- •3.3.3 Determiners (demonstrative, possessive, adjectival pronouns)

- •3.4 Quantifiers

- •3.5 Adjectives

- •3.5.1 Adjectives

- •3.5.2 Predicative (‘‘short”) adjectives

- •3.5.3 Mixed adjectives and surnames

- •3.5.4 Comparatives and superlatives

- •3.6 Declension of nouns

- •3.6.1 Categories and declension classes of nouns

- •3.6.2 Hard, soft, and unpaired declensions

- •3.6.3 Accentual patterns

- •3.6.8 Declension and gender of gradation

- •3.6.9 Accentual paradigms

- •3.7 Complications in declension

- •3.7.1 Indeclinable common nouns

- •3.7.2 Acronyms

- •3.7.3 Compounds

- •3.7.4 Appositives

- •3.7.5 Names

- •4 Arguments

- •4.1 Argument phrases

- •4.1.1 Basics

- •4.1.2 Reference of arguments

- •4.1.3 Morphological categories of nouns: gender

- •4.1.4 Gender: unpaired ‘‘masculine” nouns

- •4.1.5 Gender: common gender

- •4.1.6 Morphological categories of nouns: animacy

- •4.1.7 Morphological categories of nouns: number

- •4.1.8 Number: pluralia tantum, singularia tantum

- •4.1.9 Number: figurative uses of number

- •4.1.10 Morphological categories of nouns: case

- •4.2 Prepositions

- •4.2.1 Preliminaries

- •4.2.2 Ligature {o}

- •4.2.3 Case government

- •4.3 Quantifiers

- •4.3.1 Preliminaries

- •4.3.2 General numerals

- •4.3.3 Paucal numerals

- •4.3.5 Preposed quantified noun

- •4.3.6 Complex numerals

- •4.3.7 Fractions

- •4.3.8 Collectives

- •4.3.9 Approximates

- •4.3.10 Numerative (counting) forms of selected nouns

- •4.3.12 Quantifier (numeral) cline

- •4.4 Internal arguments and modifiers

- •4.4.1 General

- •4.4.2 Possessors

- •4.4.3 Possessive adjectives of unique nouns

- •4.4.4 Agreement of adjectives and participles

- •4.4.5 Relative clauses

- •4.4.6 Participles

- •4.4.7 Comparatives

- •4.4.8 Event nouns: introduction

- •4.4.9 Semantics of event nouns

- •4.4.10 Arguments of event nouns

- •4.5 Reference in text: nouns, pronouns, and ellipsis

- •4.5.1 Basics

- •4.5.2 Common nouns in text

- •4.5.3 Third-person pronouns

- •4.5.4 Ellipsis (‘‘zero” pronouns)

- •4.5.5 Second-person pronouns and address

- •4.5.6 Names

- •4.6 Demonstrative pronouns

- •4.7 Reflexive pronouns

- •4.7.1 Basics

- •4.7.2 Autonomous arguments

- •4.7.3 Non-immediate sites

- •4.7.4 Special predicate--argument relations: existential, quantifying, modal, experiential predicates

- •4.7.5 Unattached reflexives

- •4.7.6 Special predicate--argument relations: direct objects

- •4.7.7 Special predicate--argument relations: passives

- •4.7.8 Autonomous domains: event argument phrases

- •4.7.9 Autonomous domains: non-finite verbs

- •4.7.12 Retrospective on reflexives

- •4.8 Quantifying pronouns and adjectives

- •4.8.1 Preliminaries: interrogatives as indefinite pronouns

- •4.8.7 Summary

- •4.8.9 Universal adjectives

- •5 Predicates and arguments

- •5.1 Predicates and arguments

- •5.1.1 Predicates and arguments, in general

- •5.1.2 Predicate aspectuality and modality

- •5.1.3 Aspectuality and modality in context

- •5.1.4 Predicate information structure

- •5.1.5 Information structure in context

- •5.1.6 The concept of subject and the concept of object

- •5.1.7 Typology of predicates

- •5.2 Predicative adjectives and nouns

- •5.2.1 General

- •5.2.2 Modal co-predicates

- •5.2.3 Aspectual co-predicates

- •5.2.4 Aspectual and modal copular predicatives

- •5.2.5 Copular constructions: instrumental

- •5.2.6 Copular adjectives: predicative (short) form vs. nominative (long) form

- •5.2.9 Predicatives in non-finite clauses

- •5.2.10 Summary: case usage in predicatives

- •5.3 Quantifying predicates and genitive subjects

- •5.3.1 Basics

- •5.3.2 Clausal quantifiers and subject quantifying genitive

- •5.3.3 Subject quantifying genitive without quantifiers

- •5.3.4 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: basic paradigm

- •5.3.5 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: predicates

- •5.3.6 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: reference

- •5.3.8 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: predicates and reference

- •5.3.9 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: context

- •5.3.10 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: summary

- •5.4 Quantified (genitive) objects

- •5.4.1 Basics

- •5.4.2 Governed genitive

- •5.4.3 Partitive and metric genitive

- •5.4.4 Object genitive of negation

- •5.4.5 Genitive objects: summary

- •5.5 Secondary genitives and secondary locatives

- •5.5.1 Basics

- •5.5.2 Secondary genitive

- •5.5.3 Secondary locative

- •5.6 Instrumental case

- •5.6.1 Basics

- •5.6.2 Modal instrumentals

- •5.6.3 Aspectual instrumentals

- •5.6.4 Agentive instrumentals

- •5.6.5 Summary

- •5.7 Case: context and variants

- •5.7.1 Jakobson’s case system: general

- •5.7.2 Jakobson’s case system: the analysis

- •5.7.3 Syncretism

- •5.7.4 Secondary genitive and secondary locative as cases?

- •5.8 Voice: reflexive verbs, passive participles

- •5.8.1 Basics

- •5.8.2 Functional equivalents of passive

- •5.8.3 Reflexive verbs

- •5.8.4 Present passive participles

- •5.8.5 Past passive participles

- •5.8.6 Passives and near-passives

- •5.9 Agreement

- •5.9.1 Basics

- •5.9.2 Agreement with implicit arguments, complications

- •5.9.3 Agreement with overt arguments: special contexts

- •5.9.4 Agreement with conjoined nouns

- •5.9.5 Agreement with comitative phrases

- •5.9.6 Agreement with quantifier phrases

- •5.10 Subordinate clauses and infinitives

- •5.10.1 Basics

- •5.10.2 Finite clauses

- •5.10.4 The free infinitive construction (without overt modal)

- •5.10.5 The free infinitive construction (with negative existential pronouns)

- •5.10.6 The dative-with-infinitive construction (overt modal)

- •5.10.7 Infinitives with modal hosts (nominative subject)

- •5.10.8 Infinitives with hosts of intentional modality (nominative subject)

- •5.10.9 Infinitives with aspectual hosts (nominative subject)

- •5.10.10 Infinitives with hosts of imposed modality (accusative or dative object)

- •5.10.11 Final constructions

- •5.10.12 Summary of infinitive constructions

- •6 Mood, tense, and aspect

- •6.1 States and change, times, alternatives

- •6.2 Mood

- •6.2.1 Modality in general

- •6.2.2 Mands and the imperative

- •6.2.3 Conditional constructions

- •6.2.4 Dependent irrealis mood: possibility, volitive, optative

- •6.2.5 Dependent irrealis mood: epistemology

- •6.2.6 Dependent irrealis mood: reference

- •6.2.7 Independent irrealis moods

- •6.2.8 Syntax and semantics of modal predicates

- •6.3 Tense

- •6.3.1 Predicates and times, in general

- •6.3.2 Tense in finite adjectival and adverbial clauses

- •6.3.3 Tense in argument clauses

- •6.3.4 Shifts of perspective in tense: historical present

- •6.3.5 Shifts of perspective in tense: resultative

- •6.3.6 Tense in participles

- •6.3.7 Aspectual-temporal-modal particles

- •6.4 Aspect and lexicon

- •6.4.1 Aspect made simple

- •6.4.2 Tests for aspect membership

- •6.4.3 Aspect and morphology: the core strategy

- •6.4.4 Aspect and morphology: other strategies and groups

- •6.4.5 Aspect pairs

- •6.4.6 Intrinsic lexical aspect

- •6.4.7 Verbs of motion

- •6.5 Aspect and context

- •6.5.1 Preliminaries

- •6.5.2 Past ‘‘aoristic” narrative: perfective

- •6.5.3 Retrospective (‘‘perfect”) contexts: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.4 The essentialist context: imperfective

- •6.5.5 Progressive context: imperfective

- •6.5.6 Durative context: imperfective

- •6.5.7 Iterative context: imperfective

- •6.5.8 The future context: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.9 Exemplary potential context: perfective

- •6.5.10 Infinitive contexts: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.11 Retrospective on aspect

- •6.6 Temporal adverbs

- •6.6.1 Temporal adverbs

- •6.6.2 Measured intervals

- •6.6.3 Time units

- •6.6.4 Time units: variations on the basic patterns

- •6.6.14 Frequency

- •6.6.15 Some lexical adverbs

- •6.6.16 Conjunctions

- •6.6.17 Summary

- •7 The presentation of information

- •7.1 Basics

- •7.2 Intonation

- •7.2.1 Basics

- •7.2.2 Intonation contours

- •7.3 Word order

- •7.3.1 General

- •7.3.6 Word order without subjects

- •7.3.7 Summary of word-order patterns of predicates and arguments

- •7.3.8 Emphatic stress and word order

- •7.3.9 Word order within argument phrases

- •7.3.10 Word order in speech

- •7.4 Negation

- •7.4.1 Preliminaries

- •7.4.2 Distribution and scope of negation

- •7.4.3 Negation and other phenomena

- •7.5 Questions

- •7.5.1 Preliminaries

- •7.5.2 Content questions

- •7.5.3 Polarity questions and answers

- •7.6 Lexical information operators

- •7.6.1 Conjunctions

- •7.6.2 Contrastive conjunctions

- •Bibliography

- •Index

56 A Reference Grammar of Russian

[k] =

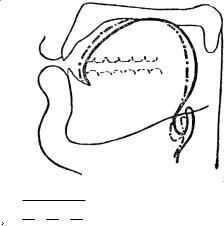

Fig. 2.13 [k], [k]˛. From Avanesov 1972:

[k] = |

fig. 20 |

|

The approximate [j] is articulated with a tongue position like that of the vowel [i], so that the blade of the tongue raises close to the hard palate behind the alveolar ridge; [j] differs from [i] in that it is not the peak of syllables and involves greater narrowing of the tongue to the front of the roof of the mouth. Given its tongue shape, [j] is intrinsically soft.

The trills [r r˛] are made by one or more taps in the dental region. With the laterals [l l˛], the blade of the tongue makes complete closure in the dental region but the sides of the tongue are raised, allowing air to pass laterally (hence the term) along its sides. Together the [r]-sounds and the [l]-sounds are liquids. Hard [r] and especially hard [l] are velarized: the middle portion of the tongue is depressed and the back of the tongue body is raised towards the back of the palate.

Collectively, the nasals, liquids (trills and laterals), and the glide [j] can be grouped together as sonorants (in notation, the set “R”), a loose class of sounds that are neither vowels nor obstruents. Sonorants can distinguish palatalization, in this respect like obstruents. Unlike obstruents, sonorants lack a distinction of voicing; like vowels, they are normally voiced, and do not cause preceding obstruents to become voiced (§2.3.9). Between an obstruent and another obstruent or word end (the contexts C/ RC/ or C/ R#), sonorants can become syllabic: MXATf

‘from MKhAT’ [ t ´m x ƒt´], jrnz´,hm ‘October’, [økt˛a55b(ə)r˛], hé,km ‘ruble’ [rub´(ə)l˛],

⁄

;∫pym ‘life’ [z˝5z˛(ə)n˛].42

‹⁄

2.3.2 Palatalization of consonants

Most consonants -- sonorants as well as obstruents -- can be palatalized or not. That is, for almost every consonantal articulation -- for almost every combination of place of articulation, manner of articulation, voicing and nasality -- there is one sound that is not palatalized and another that is pronounced with similar

42 “I pronounce the word ;bpym as two syllables, with a ‘fleeting’ *ı” (Trubetzkoy 1975:238).

Sounds 57

gestures but is palatalized. For example, both a palatalized voiced labial stop [b˛] and a non-palatalized [b] occur, and both a palatalized voiceless dental fricative [s˛] and a non-palatalized [s] occur. Palatalization is similar but not identical for sounds of different places of articulation. Though there are these minor differences, all palatalized consonants influence vowels in the same way.

When a given articulation occurs in both palatalized and non-palatalized forms, that articulation can be said to be paired, or mutable, for palatalization. Thus [b] and [b˛] are phonetically paired, or mutable. Most consonants are mutable. Labials and dentals obviously are. Velars are as well, although the palatalized forms of velars [k˛g˛x˛] are more restricted than palatalized labials or dentals; they do not occur in all phonological contexts, and they rarely if ever distinguish words in opposition to [k g x].

Some consonants are not mutable: the glide [j] (necessarily palatalized); the

hard affricate [c]; the soft affricate [c˛]; the hard fricatives [s] (Cyrillic ≤i≥) and |

|

‹ |

‹ |

[z] (Cyrillic ≤;≥). Although the alveo-palatal fricatives [s˛z˛] are palatalized, they |

|

‹ |

‹ ‹ |

are not paired with [s z] in this sense, since [s z] do not become palatalized at |

|

‹‹ |

‹‹ |

the end of noun stems in the locative singular (j lei† ‘about the soul’ has [s],

‹

not [s]˛or [s˛]) nor in the conjugation of verbs (g∫itim has [s], not [s˛]).

‹ ‹ ‹ ‹

Accordingly, four groups of consonants can be distinguished:

[2] |

hard, immutable: |

[s z c] |

|

|

‹‹ |

|

soft, immutable: |

[j c˛s˛z˛] |

|

|

‹‹ ‹ |

|

hard, mutable: |

[p t k x s z], etc. |

|

soft, mutable: |

[p t˛k˛x˛s˛z˛], etc. |

Among labials and dentals, both palatalized and non-palatalized variants occur before vowels and after vowels in word-final position. In both contexts, palatalization can distinguish words. Compare: prevocalic nj´vysq ‘languid’ [t] vs. n=vysq ‘dark’ [t˛], gƒcnm ‘fall’ [p] vs. gz´cnm ‘metacarpus’ [p]; and final postvocalic dßgbn ‘drunk down’ [t] vs. dßgbnm ‘to drink down’ [t˛], ujnj´d ‘ready’ [f] vs. ujnj´dm! ‘prepare!’ [f˛]. Because contrasts occur in final position where no vowel follows the consonant, palatalization (or its absence) must be intrinsic to the consonant, and in a phonemic analysis, it is the consonant, palatalized or not, that distinguishes words in Russian. If palatalization is distinctive for some consonants in that position, it can be assumed to be distinctive in position before a vowel. Thus the contrast of [t] in nj´vysq ‘languid’ vs. [t˛] in n=vysq ‘dark’ is usually analyzed as a contrast of two types of dental stops, non-palatalized [t] as opposed to palatalized [t˛].43

43In contrast to the abstract phonology of (for example) Lightner 1972, in which there is a rich set of vowel distinctions and consonants are intrinsically hard, becoming palatalized in the position before (underlying) front vowels.

58 A Reference Grammar of Russian

Palatalized and non-palatalized consonants occur with different degrees of freedom depending on the context (the position in the word) and depending on the consonant itself.

All mutable (phonetically paired) consonants historically were palatalized before {e} within lexemes. Palatalization therefore used not to be distinctive in the position before {e}. This historical rule, which dates from the period when palatalization first arose in Russian (a thousand years ago, in the period around the fall of the jers), has been eroded in various ways. Consonants at the end of prefixes are not palatalized before a root-initial {e} (cэrjyj´vbnm ‘economize<pf>’), nor is the final consonant of a preposition palatalized before the {e} of the demonstrative …njn ‘this’ (d …njv ‘in that’, gjl …nbv ‘under that’, c …nbv ‘with

that’, etc., with [ve], [de], [se], not [v˛e5 ], [d˛e5 ], [s˛e5 ]).

⁄ ⁄ ⁄

Consonants remain non-palatalized before {e} in abbreviations, when that {e} is word-initial in the base word from which it derives, as in YЭG ([nep], not

[*n˛e5 p] -- from “yjdfz эrjyjvbxtcrfz gjkbnbrf”). In borrowings, non-palatalized

⁄

consonants occur before {e}, despite the rule that consonants were historically palatalized before {e} (§2.3.3).44 Evidently, this primordial rule is no longer productive in all contexts.

2.3.3 The distribution of palatalized consonants

Not all contexts allow both palatalized and non-palatalized consonants. Palatalized consonants are more restricted in their distribution, but non-palatalized consonants occur freely in almost all positions except preceding the vowel {e}.45 The distribution of palatalization is sensitive to the type of consonant involved.

Dentals distinguish palatalization before all vowels except {e}. Dentals are even developing a distinction before {e} in borrowings, and are doing so more readily than other consonants. Palatalized dentals can occur when no vowel follows. Dental stops occur palatalized in final position after a dental fricative (i†cnm ‘six’, udj´plm ‘nail’ [s˛t˛] vs. i†cn ‘pole’, lhj´pl ‘thrush’ [st]). At the other end of a word, a palatalized dental stop can occur in word-initial position dissimilatively before a non-dental (nmvƒ ‘darkness’, nmaé ‘phooey’). Word-internally not before vowels, palatalized dental obstruents occur dissimilatively before velars and labials, but not before other dentals or palatals: nƒnm,f ‘thievery’, cdƒlm,f ‘wedding’, n=nmrf ‘aunt’, G†nmrf ‘Pete’. Derivational suffixes that now begin with a consonant, such as {-n}, once began with etymological m, a high front vowel which, a thousand years ago, palatalized the preceding consonant. Now consonants are not palatalized before these suffixes: -obr (ajyƒhobr but ajyƒhm

44 Glovinskaia 1971, Alekseeva and Verbitskaia 1989. |

45 Glovinskaia 1976. |

Sounds 59

‘lantern’), -xbr (kƒhxbr ‘box’ but kƒhm ‘chest’), -ybr (nhj´cnybr ‘reed’ but nhj´cnm ‘cane’), -ysq (zynƒhysq but zynƒhm ‘amber’).

Palatalized dental sonorants [r˛l˛n˛], and especially [l˛], are distributed more freely: word-finally after other consonants (vßckm ‘thought’, hé,km ‘ruble’, cgtrnƒrkm ‘spectacle’, ;ehƒdkm ‘crane’, dj´gkm ‘howl’, d∫[hm ‘whirlwind’, ;∫pym ‘life’), in comparatives (hƒymit ‘earlier’, nj´ymit ‘thinner’, v†ymit ‘less’), and in adjectives from months (jrnz´,hmcrbq ‘of October’, b÷ymcrbq ‘of June’, b÷kmcrbq ‘of July’). The lateral [l˛] has the widest distribution: gjhneuƒkmcrbq ‘Portuguese’, djltd∫kmxbr ‘vaudeville performer’.

Labials, before vowels other than {e}, can be either non-palatalized (gƒcnm ‘fall’) or palatalized (gz´cnm ‘metacarpus’). Labials are not palatalized internally before suffixes that once conditioned palatalization: rabmsk(jm > hƒ,crbq ‘servile’. Labials distinguish palatalization in word-final position after vowels: rj´gm ‘mine’ vs. jrj´g ‘trench’, ujnj´d ‘ready’ vs. ujnj´dm ‘make ready!’. They can even occur in word-final position after consonants, in [jhéudm ‘standard’, d†ndm ‘branch’. Final palatalized labials in isolated grammatical forms were lost early in the history of Russian (athematic 1sg prs damm > lfv ‘I give’, ins sg -Vmm > {-om}),46 and there is a slight tendency to lose palatalization in labials at the end of words in other instances, for example, dj´ctvm ‘eight’ [m] [m˛].

Velars [k g x] can be either palatalized or non-palatalized. For the most part, the variants are distributed in complementary fashion: the palatalized variant occurs before {i e}, the hard variant elsewhere -- before other vowels and in a position not before a vowel. However, exceptions to this strict complementarity have begun to appear. Palatalized velars occur before the [o] functioning as the ligature in the second singular through second plural of the present tense of velar-stem verbs, with varying stylistic values in different words. By now, [k˛] is standard in forms of nrƒnm ‘weave’ (2sg nr=im, etc.), while [g]˛was used by about half of speakers (in the survey of the 1960s) in ;†xm ‘burn’ (3sg ;u=n for standard ;;=n), and [k˛] by a quarter of speakers in g†xm ‘bake’ (2sg gtr=im); in the last two the palatalized velar is not normative. To the extent that present adverbial participles are permitted from velar-stem verbs (they are not universally accepted), the form has a palatalized velar (,thtuz´ ‘protecting’) by analogy to other obstruent-stem verbs (ytcz´ ‘carrying’). Palatalized velars appear before {a o u} in borrowings in the previous century: uzéh ‘giaour’, ,hfr=h ‘inspector’, r/h† ‘cur†’, vfybr÷h ‘manicure’. Palatalized velars do not occur in final, postvocalic position. Non-palatalized velars do not occur before {e i} in native words, although a non-palatalized pronunciation is normal for the [k] of the preposition r before {i} and {e}, as in r buh† ‘to the game’ or r …njve ‘to that’ or for

46 Shakhmatov 1925.

60A Reference Grammar of Russian

velars in compounds, as in lde[эnƒ;ysq ‘two-storied’ [x]. In this way, there is a contrast of sorts between palatalized [k˛] internal to morphemes (r∫yenm ‘toss’ > [k˛í]) and non-palatalized [k] in the prepositional phrase (r ∫yjre ‘to the monk’ > [k˝!]). Thus velars are moving towards developing a contrast for palatalization.

In native words, all mutable hard consonants (all hard consonants except

[c s z]) are palatalized in the position before {e}. In borrowings, a non-palatalized

‹‹

pronunciation is possible to a greater or lesser extent, depending on how well assimilated the individual word is, the familiarity of a given speaker with foreign languages, and systemic properties. When the question was investigated in the 1960s, it was found that in some words -- seemingly more ordinary, domestic words -- the frequency of a hard pronunciation was increasing: h†qc ‘route’, rjyc†hds ‘conserves’, rjyrh†nysq ‘concrete’, ,th†n ‘beret’, htp†hd ‘reserve’. With other -- more scientific -- words, the percentage of the population using palatalized consonants decreased from the oldest to youngest cohort: fhn†hbz ‘artery’, by†hwbz ‘inertia’, rhbn†hbq ‘criterion’, эy†hubz ‘energy’, ,frn†hbz ‘bacteria’. And in a third group there is no clear direction of change: ghjuh†cc ‘progress’, gfn†yn ‘patent’.47 Hard consonants are more easily maintained in stressed than in unstressed position. Dentals most frequently allow hard consonants, then labials, then velars. Yet a hard pronunciation does occur with labials and with velars: ,tvj´km ‘b-flat’ [be*mj´öl˛], v…h ‘mayor’ [m†r], g…h ‘peer’ [p†r], u†vvf ‘engraved stone’ [g†m´], r†vgbyu r…vgbyu ‘camping’ [k†mpìng], […vvjr ‘hammock’ [x†m´k],

u†nnj ‘ghetto’ ([g†] [g†]).48

˛

Overall, the possibility of having a contrast of palatalized and non-palatalized consonants depends on a number of parameters. The possibility of a contrast for palatalization depends on the place (and secondarily manner) of articulation of the consonant itself, dentals favoring the distinction more than labials, which in turn favor the distinction more than velars; yet velars at least have positional variation for palatalization, thereby ranking them ahead of the im-

mutable consonants [s z s˛z˛], [c], and [j]. Having a contrast in palatalization also

‹‹‹ ‹

depends on context. A contrast for palatalization is most likely before vowels (/ V), less likely in a position after a vowel with no vowel following; within the latter environment, palatalization is less likely than before a consonant (/V C) than in word-final position (/V #) -- perhaps because in most instances in which a palatalized consonant would appear word-finally, the given form alternates with another form in which a vowel follows (nom sg uj´ke,m ‘dove’ [p], gen sg uj´ke,z [b˛´]). Palatalized consonants are infrequent in contexts not adjacent to a vowel, though they can occur (nmvƒ ‘darkness’, ;∫pym ‘life’, hé,km ‘ruble’, [jhéudm ‘standard’). Among vowels, a distinction is made more readily before back vowels

47 Glovinskaia 1976:100--10. |

48 Glovinskaia 1971:63. |