- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Coma |

30 |

|

|

Kayanoosh Kadapatti and Shivakumar Iyer |

|

A 30-year-old male patient, who was found unconscious in his room, was brought to the emergency department. On examination, he was found to be tachypneic and febrile with normal blood pressure. He was not opening his eyes and was withdrawing arms on pain.

The comatose patient in the ICU poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the physician. A broad range of differential diagnoses necessitate a systematic approach and judicious use of investigation in these patients.

Step 1: Assess and stabilize the patient

•In any unexplained, unresponsive patient, caution should be taken to avoid cervical spine movement while managing airway.

•If there is hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dL), it should be urgently corrected with 50 mL of 25% dextrose intravenously.

•Thiamine should be given prior to glucose to avoid Wernicke’s encephalopathy, especially in patients with malnutrition and alcoholism.

•Control seizure, if present, with intravenous lorazepam.

•In patients who show features of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), 100 mL of 10% intravenous mannitol should be given (see Chap. 31).

•Give prompt antibiotics in patients with signs suggestive of meningitis.

•Check core temperature, and if hypothermic warm the patient.

K. Kadapatti, M.D., E.D.I.C. (*)

Department of Critical Care, Unit Jehangir Hospital, Pune, India e-mail: drkayanoosh@gmail.com

S. Iyer, M.D., E.D.I.C.

Department of Intensive Care Unit, Sahyadri Specialty Hospital, Pune, India

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

243 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_30, © Springer India 2012 |

|

244 |

K. Kadapatti and S. Iyer |

|

|

Step 2: Review history

Detailed history should be taken from the accompanying person:

•Rapidity of onset of the coma

•Rate of progression of coma

•The patient’s circumstances at the time of onset of coma

•Any precipitating injury or seizure

•Any history of headache or neurological symptoms

•Any recent fever or illness

•Any history of depression or suicide ideation

•Any evidence of empty pill bottles, prescription, or suicide notes

•Any known chronic medical problems

•Any previous neurosurgery, for example, intracranial shunts

•Any history of alcohol or other drug abuse

•Any known exposure to toxins, gas fumes, or possible carbon monoxide/cyanide exposure

•Recent travel

Step 3: Perform focused physical examination

•The level of consciousness may be assessed by AVPU and the Glasgow Coma Scale

A Alert

V Responds to verbal stimuli P Responds to painful stimuli U Unresponsive

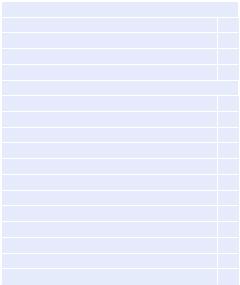

•Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Table 30.1)

Table 30.1 Glasgow Coma

Scale

Best eye opening (E)

Nil |

1 |

Pain |

2 |

Verbal |

3 |

Spontaneous |

4 |

Best verbal response (V) |

|

Nil |

1 |

Incomprehensible sounds |

2 |

Inappropriate but recognizable words |

3 |

Confused conversation |

4 |

Oriented |

5 |

Best motor response (M) |

|

Nil |

1 |

Abnormal extension (decerebrate response) |

2 |

Abnormal flexion (decorticate response) |

3 |

Withdraws to pain |

4 |

Localizes to pain |

5 |

Obeys commands |

6 |

30 Coma |

245 |

|

|

–The GCS measures the best eye, verbal, and motor response. The worst is 3 points and the best is 15 points, recorded as E4M6V5 = 15. A tracheostomy tube/ETT (endotracheal tube)/facial injury invalidates V.

•A GCS of less than 8 (e.g., E2M4V2) indicates severe traumatic brain injury. One must assess the airway carefully and decide for intubation for airway protection in this group of patients.

•Focused physical examination should be performed to assess the evidence of lateralizing signs like hemiplegia, features of increased ICP like pupillary changes, features of meningoencephalitis, or any systemic problem requiring immediate attention by imaging or neurosurgical consultation.

•Physical examination is useful in assessing the severity of coma and anatomical localization of neurological insult. These examinations need to be repeated frequently to elicit any deterioration of the patient’s status.

•Posture—look for any seizure activity, tremors, myoclonus, or spontaneous decerebration. Myoclonic jerks point toward an anoxic cause of coma and portend a bad prognosis. Subtle rhythmic movements may suggest ongoing seizures.

•Skin—look for pallor, icterus, cyanosis of methemoglobinemia, petechiae, scars, burns, pigmentation, and needle marks.

•Facial muscles—look for asymmetry of the face.

•Oral cavity—look for tongue bite, smell of alcohol or ammonia (liver disease), gingival hyperplasia (phenytoin-induced), oral thrush (immunodeficient state).

•HEENT—head, eye, ear, neck, and throat should be examined for the evidence of injury, hematoma, bleeding (Battle’s sign, Raccoon eyes) or any purulent discharge, skull fractures, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea, or otorrhea. Neck stiffness examination should be avoided in patients with suspected cervical spine injury. Check pupils for symmetry and light reflex.

•Blood pressure—elevation of blood pressure can indicate long-standing hypertension, which predisposes to intracranial hypertension or hypertensive encephalopathy due to increased ICP.

•Temperature

–Hypothermia can occur in ethanol or sedative drug intoxication, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, and myxedema.

–Hyperthermia can occur in status epilepticus, pontine hemorrhage, heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia, and anticholinergic intoxication.

•Optic fundi—look for papilledema and vitreous hemorrhage.

•Specific neurological examination of a comatose patient should include mental status, level of consciousness, awareness of self and environment, cranial nerve, motor response, and brainstem reflexes.

•Assess the brainstem reflexes

–Check pupillary size and response to light.

–Pupils that are equal in size, and react briskly to light, usually imply normal brainstem function and suggest metabolic coma or cortical injury.

–Poorly reactive (but equal) pupils offer no clinical clues to the etiology or severity of the coma.

246 |

K. Kadapatti and S. Iyer |

|

|

–Small (1–2.5 mm) reactive pupils—diencephalon (thalamic hemorrhage), metabolic encephalopathy.

–Pinpoint pupils (<1 mm) with reaction—pontine pathology, narcotic or barbiturate overdose.

–Midposition/large (5–7 mm), fixed pupils—midbrain lesion

–Bilateral widely dilated, fixed pupils—severe midbrain damage, brain death, rarely drugs, for example, barbiturates, atropine

–Unilateral, dilated, fixed pupils—third nerve compression

•Ocular movements

–Abducted eyes—third nerve dysfunction.

–Adducted eyes—sixth nerve dysfunction; increased ICP.

–Spontaneous horizontal eye movement, whether conjugate or disconjugate, implies normal brainstem function and suggests a metabolic coma.

–Induced conjugate eye movement, oculocephalic reflex (doll’s eye maneuver) or the oculovestibular reflex (cold caloric test)—in patients with suspected cervical spine injury, cold caloric test is preferable.

–Resting position of the eyes on opening the eyelids—persistent conjugate deviation of the eyes toward one side suggests a stroke or seizure. Tonic conjugate downward deviation of the eyes often implies thalamic upper brainstem compression.

–Corneal reflex should be tested by putting a few drops of sterile saline in the eyes rather than cotton wool to avoid corneal injury.

•Motor response

–Motor responses can be characterized as appropriate, posturing, or flaccid.

–Posturing refers to stereotyped arm and leg movement occurring spontaneously or elicited by sensory stimulation. Abnormal posturing can occur in early brainstem compression due to increased ICP and transtentorial herniation and manifest first with decorticate (arm flexion, leg extension) posturing due to diencephalon compression. The patient can then manifest decerebrate (arm extension, leg extension) posturing due to midbrain and upper pons compression, and further as the lower brainstem (medulla) is compressed, the extremities become flaccid. Posturing cannot be precisely used for anatomical location.

•Respiratory patterns

–Various respiratory patterns such as Cheyne–Stokes breathing and central neurogenic hyperventilation may be observed depending on the location of the lesion.

Step 4: Perform relevant diagnostic tests

•A methodical way of appropriate investigation should be adopted to elicit the cause of coma and need for any immediate surgical intervention.

•Time is of the essence as these patients may deteriorate suddenly.

•Transportation of comatose patients for imaging should be carefully monitored and airway protection should be evaluated.

30 Coma |

247 |

|

|

•A team of the intensivist, radiologist, neurophysician, neurosurgeon, and other paramedical staff is essential in coordinating the care of comatose patients.

•Complete blood count, complete metabolic profile—blood glucose, serum electrolytes (Na, K, Ca, Mg), liver function tests, ammonia, serum osmolality, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, thyroid function test, ABG—toxicologic analysis of blood and urine.

•Chest skiagram, ultrasound, ECG.

•Cranial CT/MRI.

•CSF analysis.

•EEG.

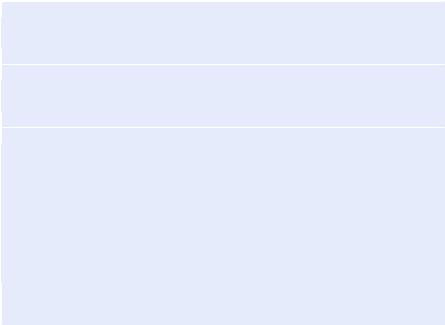

Step 5: Ascertain the cause of coma and treat if possible (Table 30.2)

•Structural lesions can cause coma in one of two ways: directly by injuring the reticular activating system itself (e.g., brainstem stroke or hemorrhage) or indirectly by compression on the RAS (reticular activating system).

•This process is due to herniation whereby a mass lesion or swelling causes displacement of cerebral structures, ultimately compressing the brainstem, often in a rostrocaudal pattern.

•Look for common causes of structural coma (Table 30.2).

•Toxins and drugs account for an important cause of coma, which affects the brain diffusely and must be thought of in every patient of coma with normal brain imaging.

Table 30.2 Causes of coma

Supratentorial lesions

Subdural or extradural hematomas

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Infarction, tumor, abscess, and hydrocephalus

Infratentorial lesions

Brainstem infarct or hemorrhage

Cerebellar infarct

Hemorrhage, tumors, or abscesses

Diffuse cerebral or metabolic

Hypoxia Concussion

Meningitis, encephalitis, sepsis

Seizures (postictal states or status epilepticus) Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Endocrine disturbances (hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis hyperosmolar state, myxedema, hyperthyroidism)

Electrolyte abnormalities (hyponatremia, hypernatremia) Endogenous toxins or deficiencies (uremia, hepatic failure)

Exogenous toxins or drugs (benzodiazepines, barbiturates, anticonvulsants, opiate analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, organophosphorus compounds, anesthetic drugs, narcotic overdose in ICU, cyanide, carbon monoxide poisoning)