- •Preface

- •Foreword

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Medical History

- •1.1 Congestive Heart Failure

- •1.2 Angina Pectoris

- •1.3 Myocardial Infarction

- •1.4 Rheumatic Heart Disease

- •1.5 Heart Murmur

- •1.6 Congenital Heart Disease

- •1.7 Cardiac Arrhythmia

- •1.8 Prosthetic Heart Valve

- •1.9 Surgically Corrected Heart Disease

- •1.10 Heart Pacemaker

- •1.11 Hypertension

- •1.12 Orthostatic Hypotension

- •1.13 Cerebrovascular Accident

- •1.14 Anemia and Other Blood Diseases

- •1.15 Leukemia

- •1.16 Hemorrhagic Diatheses

- •1.17 Patients Receiving Anticoagulants

- •1.18 Hyperthyroidism

- •1.19 Diabetes Mellitus

- •1.20 Renal Disease

- •1.21 Patients Receiving Corticosteroids

- •1.22 Cushing’s Syndrome

- •1.23 Asthma

- •1.24 Tuberculosis

- •1.25 Infectious Diseases (Hepatitis B, C, and AIDS)

- •1.26 Epilepsy

- •1.27 Diseases of the Skeletal System

- •1.28 Radiotherapy Patients

- •1.29 Allergy

- •1.30 Fainting

- •1.31 Pregnancy

- •Bibliography

- •2.1 Radiographic Assessment

- •2.2 Magnification Technique

- •2.4 Tube Shift Principle

- •2.5 Vertical Transversal Tomography of the Jaw

- •Bibliography

- •3. Principles of Surgery

- •3.1 Sterilization of Instruments

- •3.2 Preparation of Patient

- •3.3 Preparation of Surgeon

- •3.4 Surgical Incisions and Flaps

- •3.5 Types of Flaps

- •3.6 Reflection of the Mucoperiosteum

- •3.7 Suturing

- •Bibliography

- •4.1 Surgical Unit and Handpiece

- •4.2 Bone Burs

- •4.3 Scalpel (Handle and Blade)

- •4.4 Periosteal Elevator

- •4.5 Hemostats

- •4.6 Surgical – Anatomic Forceps

- •4.7 Rongeur Forceps

- •4.8 Bone File

- •4.9 Chisel and Mallet

- •4.10 Needle Holders

- •4.11 Scissors

- •4.12 Towel Clamps

- •4.13 Retractors

- •4.14 Bite Blocks and Mouth Props

- •4.15 Surgical Suction

- •4.16 Irrigation Instruments

- •4.17 Electrosurgical Unit

- •4.18 Binocular Loupes with Light Source

- •4.19 Extraction Forceps

- •4.20 Elevators

- •4.21 Other Types of Elevators

- •4.22 Special Instrument for Removal of Roots

- •4.23 Periapical Curettes

- •4.24 Desmotomes

- •4.25 Sets of Necessary Instruments

- •4.26 Sutures

- •4.27 Needles

- •4.28 Local Hemostatic Drugs

- •4.30 Materials for Tissue Regeneration

- •Bibliography

- •5. Simple Tooth Extraction

- •5.1 Patient Position

- •5.2 Separation of Tooth from Soft Tissues

- •5.3 Extraction Technique Using Tooth Forceps

- •5.4 Extraction Technique Using Root Tip Forceps

- •5.5 Extraction Technique Using Elevator

- •5.6 Postextraction Care of Tooth Socket

- •5.7 Postoperative Instructions

- •Bibliography

- •6. Surgical Tooth Extraction

- •6.1 Indications

- •6.2 Contraindications

- •6.3 Steps of Surgical Extraction

- •6.4 Surgical Extraction of Teeth with Intact Crown

- •6.5 Surgical Extraction of Roots

- •6.6 Surgical Extraction of Root Tips

- •Bibliography

- •7.1 Medical History

- •7.2 Clinical Examination

- •7.3 Radiographic Examination

- •7.4 Indications for Extraction

- •7.5 Appropriate Timing for Removal of Impacted Teeth

- •7.6 Steps of Surgical Procedure

- •7.7 Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Teeth

- •7.8 Extraction of Impacted Maxillary Teeth

- •7.9 Exposure of Impacted Teeth for Orthodontic Treatment

- •Bibliography

- •8.1 Perioperative Complications

- •8.2 Postoperative Complications

- •Bibliography

- •9. Odontogenic Infections

- •9.1 Infections of the Orofacial Region

- •Bibliography

- •10. Preprosthetic Surgery

- •10.1 Hard Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •10.2 Soft Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •Bibliography

- •11.1 Principles for Successful Outcome of Biopsy

- •11.2 Instruments and Materials

- •11.3 Excisional Biopsy

- •11.4 Incisional Biopsy

- •11.5 Aspiration Biopsy

- •11.6 Specimen Care

- •11.7 Exfoliative Cytology

- •11.8 Tolouidine Blue Staining

- •Bibliography

- •12.1 Clinical Presentation

- •12.2 Radiographic Examination

- •12.3 Aspiration of Contents of Cystic Sac

- •12.4 Surgical Technique

- •Bibliography

- •13. Apicoectomy

- •13.1 Indications

- •13.2 Contraindications

- •13.3 Armamentarium

- •13.4 Surgical Technique

- •13.5 Complications

- •Bibliography

- •14.1 Removal of Sialolith from Duct of Submandibular Gland

- •14.2 Removal of Mucus Cysts

- •Bibliography

- •15. Osseointegrated Implants

- •15.1 Indications

- •15.2 Contraindications

- •15.3 Instruments

- •15.4 Surgical Procedure

- •15.5 Complications

- •15.6 Bone Augmentation Procedures

- •Bibliography

- •16.1 Treatment of Odontogenic Infections

- •16.2 Prophylactic Use of Antibiotics

- •16.3 Osteomyelitis

- •16.4 Actinomycosis

- •Bibliography

- •Subject Index

118 F. D. Fragiskos

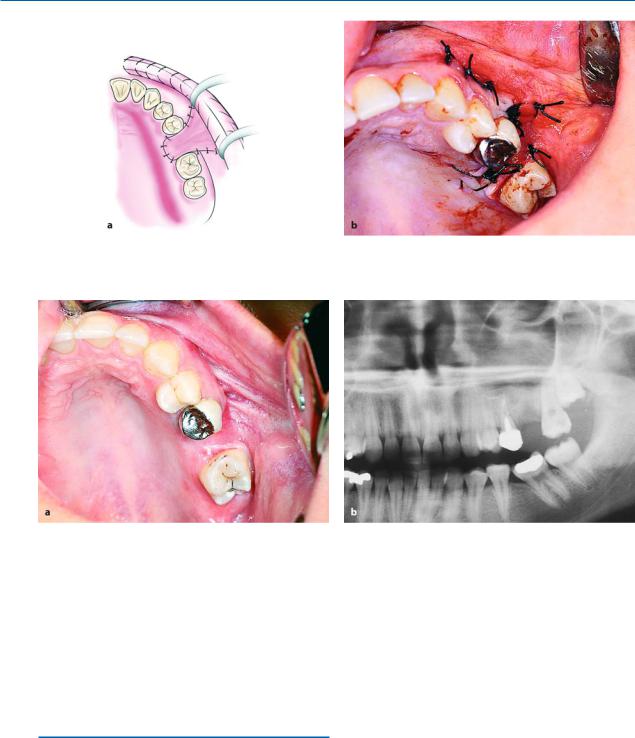

Fig. 6.76 a, b. Stabilization of the flap over the postextraction socket with sutures. a Diagrammatic illustration. b Clinical photograph

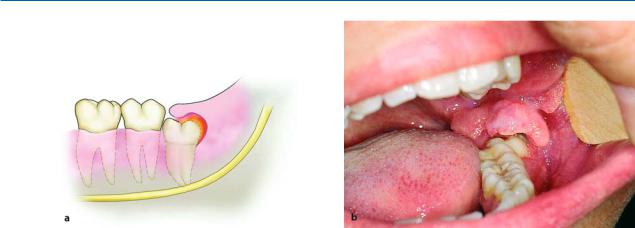

Fig. 6.77 a, b. Clinical photograph (a) and radiograph (b) 2 months after the surgical procedure

been reflected and debrided (Fig. 6.76). Postoperative care includes administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics and decongestants of the nasal mucosa (0.1% xylometazoline spray or solution) for approximately 1 week. The sutures are removed 10 days after the surgical procedure and the patient returns for a postoperative check-up about 2 months later (Fig. 6.77 a, b).

Bibliography

Archer WH (1975) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, 5th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

Cerny R (1978) Removing broken roots: a simple method. Aust Dent J 23:351–352

Gans BJ (1972) Atlas of oral surgery. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo. Hayward JR (1976) Oral surgery. Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

Hooley JR, Golden DP (1994) Surgical extractions. Dent Clin North Am 38:217–236

Hooley JR, Whitacre RA (1986) A self-instructional guide to oral surgery in general practice, vol 2, 5th edn. Stoma, Seattle, Wash.

Howe GL (1996) The extraction of teeth, 2nd edn. Wright, Oxford

Howe GL (1997) Minor oral surgery, 3rd edn. Wright, Oxford

Javaheri DS, Garibaldi JA (1997) Forceps extraction of teeth with severe internal root resorption. J Am Dent Assoc 128(6):751–754

Killey HC, Seward GR, Kay LW (1975) An outline of oral surgery. Part I. Wright, Bristol

Koerner KR (1995) Predictable exodontia in general practice. Dent Today 14(10):52, 54, 56–61

Koerner KR, Tilt LV, Johnson KR (1994) Color atlas of minor oral surgery. Mosby-Wolfe, London

Chapter 6 Surgical Tooth Extraction |

119 |

Kruger GO (1984) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, 6th edn. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Laskin DM (1985) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, vol 2. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Lehtinen R, Ojala T (1980) Rocking and twisting moments in extraction of teeth in the upper jaw. Int J Oral Surg 9(5):377–382

Leonard MS (1992) Removing third molars: a review for the general practitioner. J Am Dent Assoc 123:77–86

Lopes V, Mumenya R, Feinmann C, Harris M (1995) Third molar surgery: an audit of the indications for surgery, post-operative complaints and patient satisfaction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 33:33–35

Malden N (2001) Surgical forceps techniques. Dent Update 28(1):41–44

Martis CS (1990) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, vol 1. Athens

Masoulas G (1984) Tooth extractions. Athens

McGowan DA (1989) An atlas of minor oral surgery. Principles and practice. Dunitz-Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Ojala T (1980) Rocking moments in extraction of teeth in the lower jaw. Int J Oral Surg 9(5):367–372

Peterson LJ, Ellis E III, Hupp JR, Tucker MR (1993) Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Quinn JH (1997) The use of rotational movements to remove mandibular molars. J Am Dent Assoc 128(12):1705– 1706

Rounds CE (1962) Principles and technique of exodontia, 2nd edn. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Sailer HF, Pajarola GF (1999) Oral surgery for the general dentist. Thieme, Stuttgart

Sullivan SM (1999) The principles of uncomplicated exodontia: simple steps for safe extractions. Compendium Cont Educ Dent 20(3 Spec No):3–9, quiz 19

Summers L (1975) Oral surgery in general dental practice. The removal of roots. Aust Dent J 20(2):107–111

Thoma KH (1969) Oral surgery, vol 1, 5th edn. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Waite DE (1987) Textbook of practical oral and maxillofacial surgery, 3rd edn. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, Pa.

Chapter 7

Of the surgical procedures performed in the oral cavity, the removal of impacted and semi-impacted teeth is the most common. The extraction of these teeth, depending on their localization, may prove to be relatively easy or extremely difficult and laborious. Regardless of the degree of difficulty of the surgical procedure though, its success primarily depends on correct preoperative evaluation and planning, as well as on the treatment of complications that may arise during the procedure, or the management of complications that may present after the surgical procedure. For these reasons, a medical history, clinical examination of the patient, and radiographic evaluation of the area surrounding the impacted tooth are deemed necessary.

7.1

Medical History

A detailed medical history is necessary because, based on the information provided in Chap. 1, useful information may be found concerning the general health of the patient to be operated on. This information determines the preoperative preparation of the patient, as well as the postoperative care instructions.

7.2

Clinical Examination

During the intraoral clinical examination, the degree of difficulty of access to the tooth is determined, especially concerning impacted third molars. When the patient cannot open his or her mouth, because of trismus that is mainly due to inflammation, the trismus is treated first, and extraction of the third molar is performed at a later date. In certain cases of impacted teeth, especially canines, buccal or palatal protuberance may be observed during palpation or even inspection, which suggests that the impacted tooth is located underneath. Also, the adjacent teeth are examined and inspected (extensive caries, large amalgam

Surgical Extraction |

7 |

of Impacted Teeth |

F. D. Fragiskos

restorations, prosthetic appliance, etc.) to ensure their integrity during manipulations with various instruments during the extraction procedure.

7.3

Radiographic Examination

The radiographic examination provides us with all the necessary information to program and correctly plan the surgical removal of impacted teeth. This information includes: position and type of impaction, relationship of impacted tooth to adjacent teeth, size and shape of impacted tooth, depth of impaction in bone, density of bone surrounding impacted tooth, and the relationship of the impacted tooth to various anatomic structures, such as the mandibular canal, mental foramen, and the maxillary sinus. These aforementioned data may also be provided by periapical radiographs and panoramic radiographs, as well as occlusal radiographs (see Chap. 2).

7.4

Indications for Extraction

Specialists have divergent points of view concerning the necessity to extract impacted teeth.

Certain people suggest that the removal of impacted teeth is necessary as soon as their presence is confirmed, which is usually by chance. They even believe that it must be done as soon as possible, as long as there is no possibility that the impacted tooth may be brought into alignment in the dental arch using a combination of orthodontic and surgical techniques.

On the other hand, others suggest that the preventive removal of asymptomatic impacted teeth, besides subjecting the patient to undue discomfort, entails the risk of causing serious local complications (e.g., nerve damage, displacement of the tooth into the maxillary sinus, fracture of the maxillary tuberosity, loss of support of adjacent teeth, etc.). As far as impacted teeth that have already caused problems are concerned,

122 F. D. Fragiskos

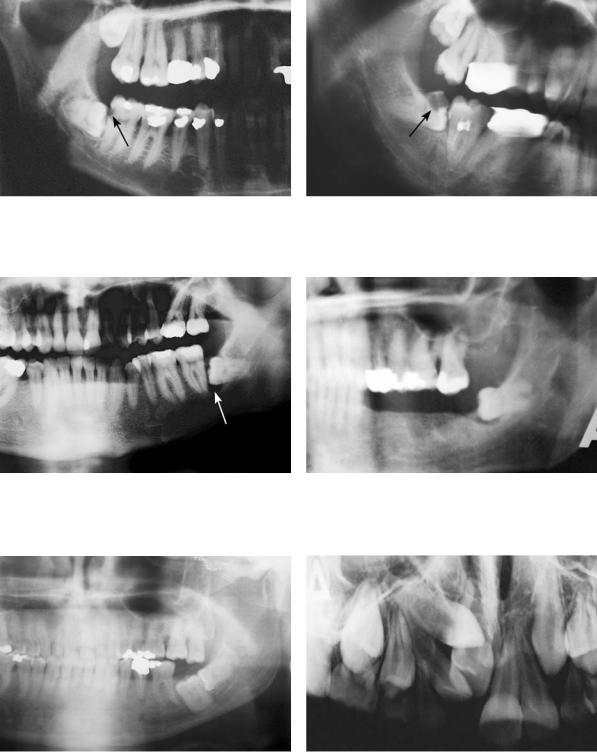

Fig. 7.1 a, b. Pericoronitis in a semi-impacted mandibular third molar. a Diagrammatic illustration showing inflammation under the operculum and distal to the crown of the

everyone agrees that they should be removed, regardless of the degree of difficulty of the surgical procedure. The most common of these problems are now given.

Localized or Generalized Neuralgias of the Head.

Impacted teeth may be responsible for a variety of symptoms related to headaches and various types of neuralgias. If this is the case, the pain may be due to pressure exerted by the impacted tooth where it comes into contact with many nerve endings. Many people suggest that the symptoms may subside after the removal of the offending tooth, which basically involves ectopic impacted teeth.

Pericoronitis. This is an acute infection of the soft tissues covering the semi-impacted tooth and the associated follicle (Fig. 7.1). This condition may be due to injury of the operculum (soft tissues covering the tooth) by the antagonist third molar or because of entrapment of food under the operculum, resulting in bacterial invasion and infection of the area. After inflammation occurs, it remains permanent and causes acute episodes from time to time. It presents as severe pain in the region of the affected tooth, which radiates to the ear, temporomandibular joint, and posterior submandibular region. Trismus, difficulty in swallowing, submandibular lymphadenitis, rubor, and edema of the operculum are also noted. A characteristic of pericoronitis is that when pressure is applied to the operculum, severe pain and discharge of pus are observed. Acute pericoronitis is often responsible for the spread of infection to various regions of the neck and facial area.

tooth. b Clinical photograph. Characteristic swelling of the operculum due to constant biting from the antagonist

Production of Caries. Entrapment of food particles and bad hygiene, due to the presence of the semi-im- pacted tooth, may cause caries at the distal surface of the second molar, as well as on the crown of the impacted tooth itself (Figs. 7.2, 7.3).

Decreased Bone Support of Second Molar. The well-timed extraction of a semi-impacted tooth presenting a periodontal pocket ensures the avoidance of resorption of the distal bone aspect of the second molar, which would result in a decrease of its support (Fig. 7.4).

Obstruction of Placement of a Partial or Complete Denture. The impacted teeth of edentulous patients can erupt towards the residual alveolar ridge, creating problems when applying a prosthesis (Fig. 7.5). The localization of the tooth is often observed after its communication with the oral cavity and the presence of pain and edema.

Obstruction of the Normal Eruption of Permanent Teeth. Impacted teeth and supernumerary teeth often hinder the normal eruption of permanent teeth, creating functional and esthetic problems (Figs. 7.6,

7.7).

Provoking or Aggravating Orthodontic Problems.

Lack of room in the arch is possibly the most common indication for extraction, primarily of impacted and semi-impacted third molars of the maxilla and mandible.

Chapter 7 Surgical Extraction of Impacted Teeth |

123 |

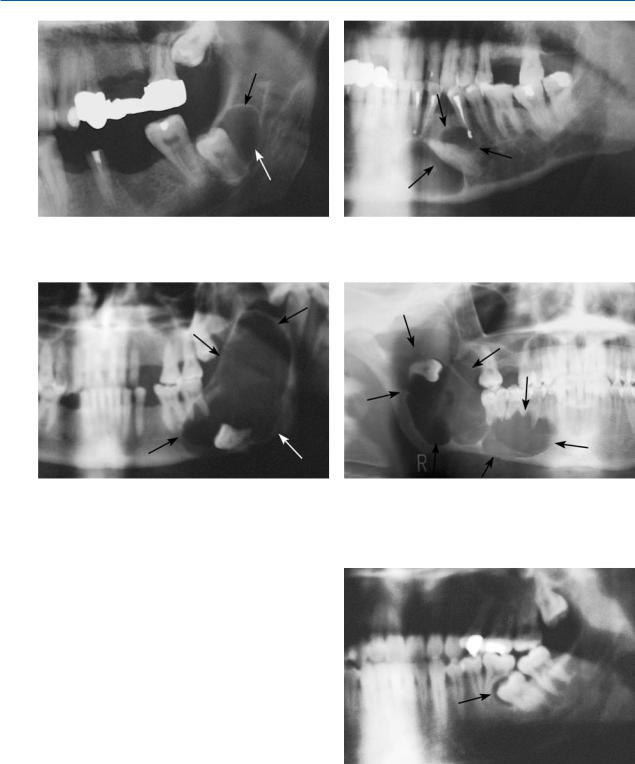

Fig. 7.2. Caries on the distal surface of the second molar, caused by a semi-impacted mandibular third molar

Fig. 7.4. Bone resorption at the distal surface of the root of a mandibular second molar, resulting in a periodontal pocket

Fig. 7.3. Caries in the distal area of the crown of semiimpacted third molar, due to entrapment of food and bad hygiene

Fig. 7.5. Impacted mandibular third molar in edentulous area, which erupted after placement of a partial denture

Fig. 7.6. Obstruction of the eruption of a mandibular second molar because of an impacted third molar

Fig. 7.7. Impacted maxillary central incisor, whose eruption was obstructed because of a supernumerary tooth

124 F. D. Fragiskos

Fig. 7.8. Impacted mandibular third molar with well-de- fined radiolucency at the distal area

Fig. 7.10. Extensive radiolucent lesion in the posterior area of the mandible, occupying the ramus. The impacted tooth has been displaced to the inferior border of the mandible

Participation in the Development of Various Pathologic Conditions. The coexistence of an impacted tooth and various pathologic conditions is not an uncommon phenomenon. Often cystic lesions develop around the crown of the tooth and are depicted on the radiograph as different-sized radiolucencies (Figs. 7.8,

7.9). These cysts may be large and may displace the impacted tooth to any position in the jaw (Figs. 7.10, 7.11).

When the presence of such osteolytic lesions is verified radiographically, they must be removed together with the associated impacted tooth.

Destruction of Adjacent Teeth Due to Resorption of Roots. Resorption of the roots of adjacent teeth is another undesirable situation that may be caused by the impacted tooth; the effect is brought about through pressure. This case primarily involves the posterior teeth of the maxilla and mandible. It begins with resorption of the distal root and, eventually, may totally

Fig. 7.9. Impacted mandibular canine that is surrounded by a lesion

Fig. 7.11. Extensive radiolucent lesion in the mandible, extending from the mandibular notch as far as the canine. The impacted tooth has been displaced to an area high in the ramus of the mandible

Fig. 7.12. Complete resorption of the distal root of the left mandibular first molar, due to an impacted second molar